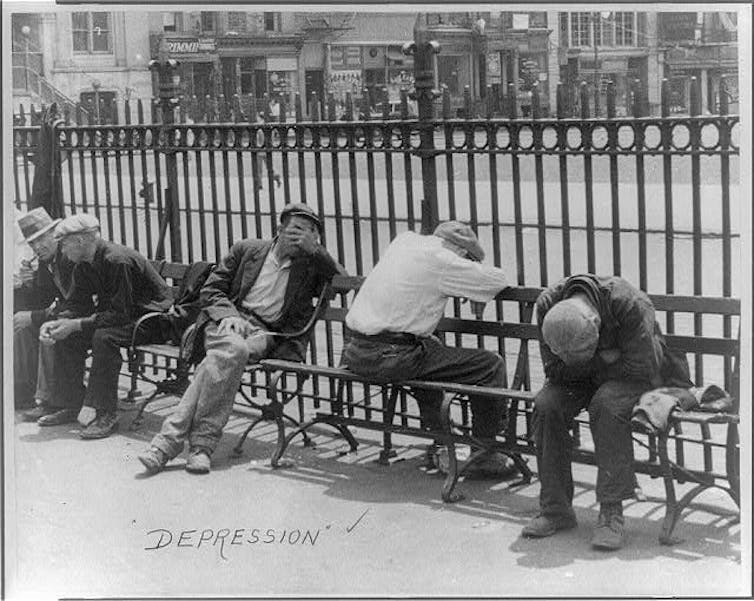

Financial crises are periods characterised by devastating losses of income, work, a certain future, and a stable family life. The effect on mental health can be catastrophic. But what does the evidence tell us about who is most at risk, and in what ways?

We are the first team to do a systematic review of global research linking financial crises and mental harms. The evidence from almost 100 eligible studies (out of nearly 7,000 we considered) shows that these crises have consistent, long-term negative effects on the wellbeing of whole groups of people, including increases in depression, anxiety and risk of suicide.

But not everyone is affected equally. Your gender, age, job and whether you have a family are all key factors in determining how vulnerable you are to the stress and poor mental health associated with financial loss and insecurity.

Across the world, we’re seeing unprecedented levels of mental illness at all ages, from children to the very old – with huge costs to families, communities and economies. In this series, we investigate what’s causing this crisis, and report on the latest research to improve people’s mental health at all stages of life.

Manual workers (such as farmers, tradespeople and those working minimum-wage jobs) are vulnerable as they typically have less of a safety net, while small business owners are particularly susceptible to financial pressures and worries.

People at either end of the age spectrum are also more vulnerable as they have fewer resources. Others at higher risk include families, people with lower levels of formal education, and those with long-term health conditions.

Suicide mortality rates increase both during and after periods of financial crisis – a risk that is always higher among men.

However, women are more at risk of suffering poorer mental health in general during a financial crisis, as they tend to take on more responsibilities both at work and home – including increased emotional labour supporting others who may be struggling financially.

Stigma, stress and social roles

Our research highlights three broad challenges to the mental wellbeing of people struggling in a financial crisis. Understanding how to address them could help make people more psychologically resilient in the face of future financial downturns. Here are some recommendations based both on the study’s findings and our combined research knowledge and expertise in health psychology.

1. Social stigma and support

The stigma of mental illness is decreasing in many societies, as we’ve become more comfortable talking about our wellbeing. It’s less clear, though, if we are okay talking about our finances. Encouraging people to be more open about financial distress with trusted friends, family members and partners, free of any judgment, can be especially important during periods of economic uncertainty.

Higher levels of trust in other people offer another defence against mental distress during periods of financial crisis. The reduced stigma around discussing mental health and suicide can buffer against some of the most devastating outcomes. Research shows that talking about suicide can save lives.

2. Stress and insecurity from loss of resources

Even if your job feels secure, financial downturns can lead to increasing pressures at work as a result of greater workloads and reduced staff.

If you are an employee, check whether your employer subscribes to an employee assistance programme that delivers legal and financial advice and psychological support when needed.

Alternatively, join a union – most provide legal advice and financial support. Practical support for business owners is also available.

When feeling threatened with loss of income or job security, connecting with people in similar positions both in-person and online, such as via parent groups, can help you feel you’re not alone and is a good way of sharing resources. You should also be able to get help from your local council.

3. Challenges to identity, social roles and meaning

Losing your job or income understandably damages your sense of self. But identity and meaning can be found in various aspects of life, not only work.

Be careful not to think of yourself as “just one thing” – whether a breadwinner or a carer – as this can create a sense of fragility. Strive to find greater meaning through family, hobbies, organisations and community work.

And we all need to encourage understanding that it’s not the sole responsibility of women to be the emotional caregivers in families and other care situations – a perception that can damage their sense of identity. Household work and childcare should be divided as evenly as possible at all times, but especially among periods of crisis when people are feeling highly stressed.

Saving lives and the economy

Declines in mental health should not be regarded as an unavoidable cost of financial crises – this is wrong economically as well as morally. Supporting a nation’s wellbeing could save a struggling economy billions by reducing mental illness-related sickness and disability, and ensuring that optimal work practices can continue.

Our review highlights that the way societies are structured affects the impact of financial crises on their populations’ mental health. It is perhaps not surprising, for example, that countries with particularly strong welfare systems, such as Iceland, reported minimal to no increases in suicide rates following a financial crisis.

At a national level, having strong welfare, accessible health services and progressive attitudes towards mental health are shown to reduce suicide and mental illness. On an individual basis, reaching out to others, having supportive social networks, rethinking our identities and developing financial knowledge may help us all weather current and future crises.

Whatever stage in life you are in, it’s a good idea to familiarise yourself with available mental health services. In the UK, for professional help, contact your GP, use the NHS e-referral platform or check out the NHS talking therapies services. Charities and organisations such as Mind, Samaritans and the Mental Health Foundation also provide expert advice and professional support.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.