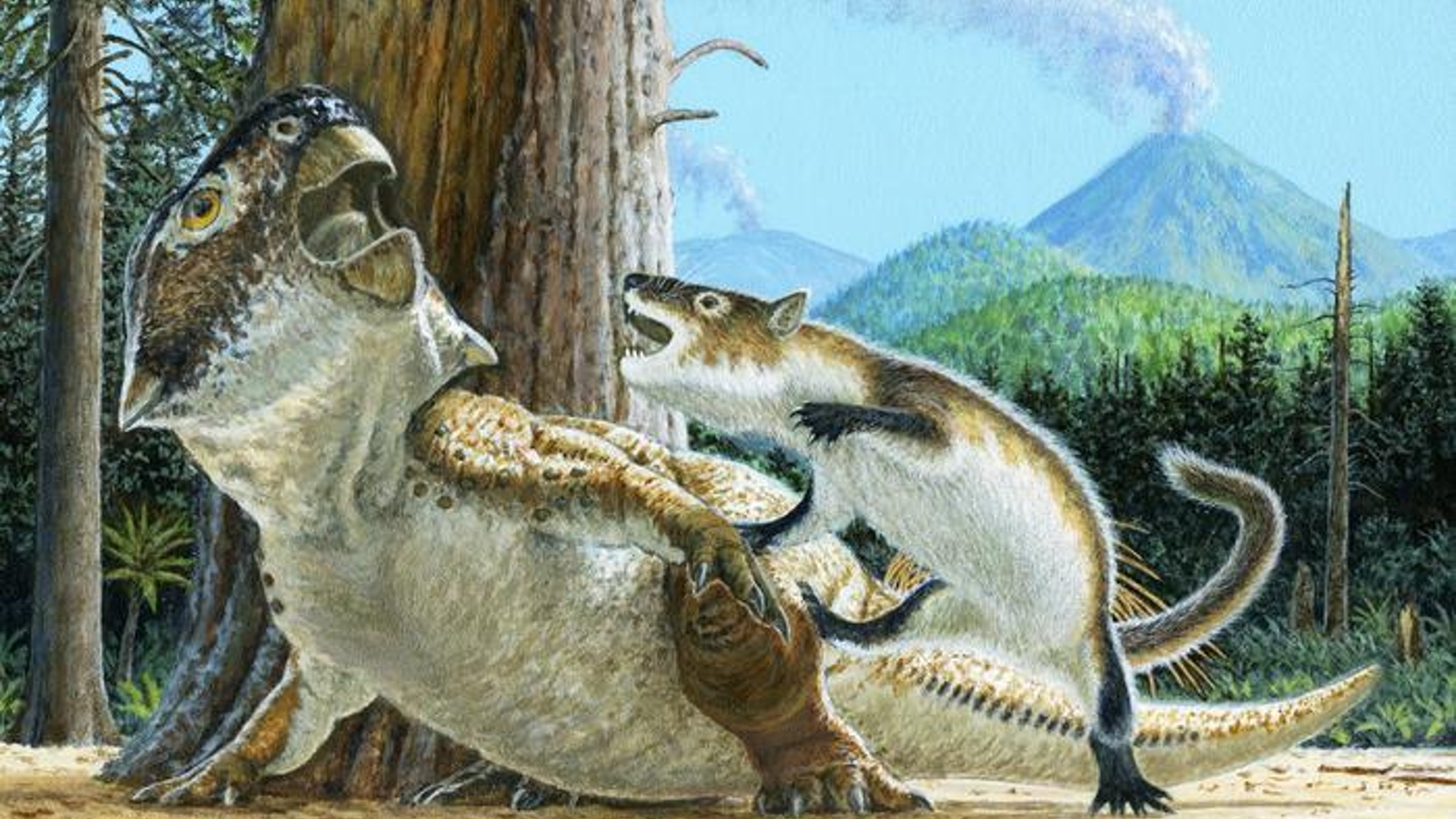

A small badger-like mammal and a young bipedal dinosaur were locked in "mortal combat" around 125 million years ago before being entombed by a sudden volcanic eruption, creating a stunning fossil that perfectly preserves their fight to the death.

The epic fossil was unearthed from the Liujitun fossil beds in China’s Liaoning Province in 2012. The area has been dubbed "China’s dinosaur Pompeii" because volcanic mudflows during the mid-Mesozoic era rapidly covered the area and perfectly preserved the unfortunate creatures in its path.

The newly described stone slab contains the skeletons of two species — Repenomamus robustus, an extinct badger-like creature that was one of the largest mammals alive at the time, and a dinosaur in the genus Psittacosaurus, a group of plant-eating horned dinosaurs with bird-like beaks and long filaments at the ends of their tails. The mammal measures around 18.5 inches (47 centimeters) long from nose to tail, while the dinosaur measures around 47 inches (120 cm) long. Based on the sizes of past fossils, this suggests that both creatures weren't fully grown adults.

Researchers described the dueling animals in a new paper, which was published July 18 in the journal Scientific Reports.

Related: 10 stunning fossils from 2022 that didn't come from dinosaurs

The study researchers found that the small mammal likely won the fight, apparently delivering a lethal blow to the larger dinosaur before they were both entombed by scorching hot mud.

"The dinosaur is lying prone on its front with its hindlimbs folded on either side of its body and its neck and tail curled to the left," researchers wrote in the study, while "the mammal lies on top of the dinosaur’s left side and curves to the right." The left front paw of R. robustus is also gripping the dinosaur's lower jaw, while the mammal's left hind paw appears to grip the dinosaur's left shin, they added.

But the most convincing evidence that R. robustus was the winner is that the mammal's teeth were embedded in the dinosaur's ribcage when the animals died, having potentially just delivered the killing blow, the researchers wrote.

In the past, bones from a Psittacosaurus dinosaur have also been found in the stomach of another fossilized R. robustus, the researchers wrote. In that case, however, scientists couldn't determine whether the mammal had managed to overpower its prey or was simply scavenging a dinosaur's remains. But the lack of additional bite marks on the dinosaur in the new fossil suggests that R. robustus was likely a regular predator of Psittacosauruses.

The new finding upends what researchers have long assumed about dinosaurs and mammals — that the extinct reptiles mainly hunted mammals and not the other way around, study co-author Jordan Mallon, a palaeobiologist with the Canadian Museum of Nature in Ottawa, said in a statement. "It's among the first evidence to show actual predatory behavior by a mammal on a dinosaur."

The researchers want to return to the Liujitun fossil beds to uncover more perfectly preserved paleontological treasures and further understand the ecological relationships between the two animal groups.