Great-grandmothers. We all have them. But most of us will never know them except through glimpses of fading bits of paper: sepia photographs, recipe cards, letters in handwriting traced by a fountain pen dispensing cocoa-colored ink.

What does it take to build coherent stories out of such tantalizing fragments of lives? I face this question routinely in my career as a professor of 19th-century literature and culture. Recently, I’ve turned that experience to writing a book about my own family.

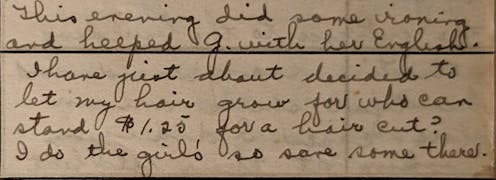

When I inherited my great-grandmother’s diary, a repurposed teacher’s planner in which she chronicled the family’s 1926 move from Michigan to Miami, I found a wedding portrait tucked inside. The angled profile showcases her youthful skin and a dress too elaborate for a Midwestern schoolteacher’s daily wear. It is easy to imagine that she took pleasure in inscribing her new name on the picture’s reverse: Faith Avery.

I stared at her beautiful image for years, as if details of her satin gown could explain why a woman widowed in 1918 would, for the rest of her life, refuse to admit to having had that first husband and yet carefully preserve this portrait.

And then, because archives have been at the center of my scholarly work, I turned to research. I located marriage records and draft cards, pored over maps, found family members in censuses and obituaries. Within those documents lay answers both surprising and poignant.

What did I look for? How might anyone with a half-told family story begin to uncover more truths? And what does it take to make sense of them?

The digging

Questions that begin with “why” can rarely be answered easily. Researchers thus often prefer to start with “who” and “when” and “how,” locating a person in one spot and then tracing them through time. This adventure down a rabbit hole follows a method.

Make a list of unknowns. These may be facts or enticing tidbits of incomplete family lore. My mother, trying to be helpful, told me things like, “Faith always said there was a horse thief in the family, but she was too mortified to reveal his name” and “I think Aunt Harriette (Faith’s sister) was married once briefly.”

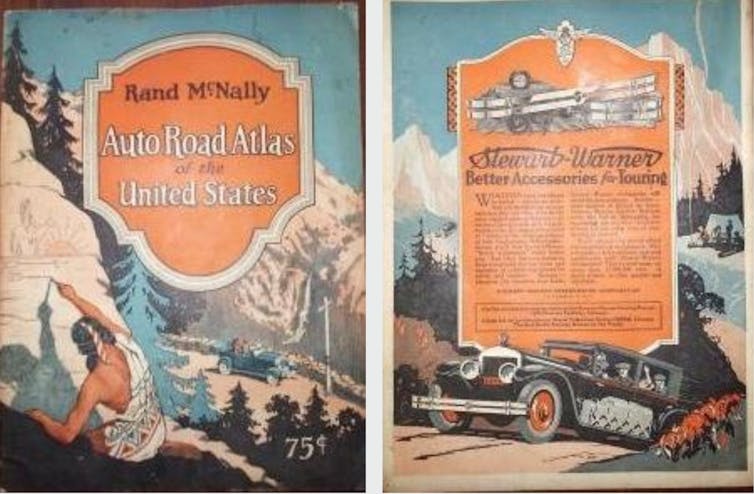

Do precise, not general, searches. Typing “horse thief Avery” into Google yields nothing useful, but many other sources contain rich information about old-fashioned exploits. The New York Public Library’s guide for family research introduces some options. The Library of Congress print and photograph collection can also help you envision your ancestors’ world. Physical libraries contain historic photographs, maps, local records and digitized newspapers not available online. Historical societies and state universities typically allow free, in-person use of their collections.

Know that sometimes you will fail and need to change course. I spent several days looking for the horse thief to no avail, much to my mother’s disappointment. But when I turned to Aunt Harriette’s marriage, I found a character no less fascinating, one I now think of as “Four Wives Frank.”

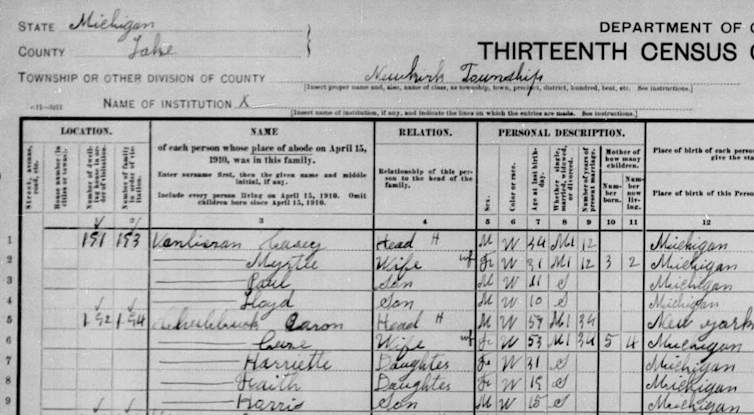

Read old documents knowing they were produced by a patchwork of individuals who took information on trust. The handwritten birth, death, marriage and census records of past centuries relied on self-reported data that required no verification. They can be plagued by carelessness in the name of efficiency.

One hurried census-taker recorded Faith’s mother Cara as “Cora,” another renamed her brother Horace “Harris.” Frank offered up a variety of birth years, countries of origin and maiden names for his mother as he worked his way west. He must have been charming. Who but a charming man could have convinced woman after woman to marry him, each thinking she was, at most, his second wife? Marriage register officers and census-takers, not to mention his trail of brides, were none the wiser.

Which leads me to this: Cross-check information. I knew I had the right Frank because he had the same three sons in multiple records. Inconsistencies across those records, in conjunction with the trajectory of his life, made this conclusion inevitable: The man purposefully reinvented himself.

The assembly

My academic work has taught me that most archival answers lead to more questions. As a result, I expect multiple phases of collecting. I gathered everything I could find about Faith’s early life, in hopes something might explain her reticence about her first marriage. As her story emerged, I periodically hit holes in the narrative that sent me back for more digging.

Understanding people is easier if you are familiar with their world. For background, I read histories of Miami in the 1920s and researched details in Faith’s diary that might reveal her personality or motivations. Exploring her reading lists showed me a woman who enjoyed popular entertainment, such as 1926’s blockbuster “Aloma of the South Seas.” Primers of 1920s wages and prices explained the family’s economic worries.

As I got to know Faith, I revisited documents with new questions. To figure out whether Harriette’s husband Frank had anything to do with Faith, I made timelines for both sisters. To ponder the emotional underpinnings of those events, I reread Faith’s diary, paying particular attention to entries about Harriette and about Faith’s second husband.

Because every pile of documents contains multiple stories, the key to a coherent narrative is locating a through line that addresses the biggest conundrums while identifying the tangents. I let go of the horse thief.

The results

The detective-style plots of what I call “investigative memoir” may inspire you to do your own family research. Genealogy sites such as Ancestry.com and FamilySearch.org can help.

But it’s worth remembering that secondary reading will add richness to any family story. And local librarians are extraordinary at helping patrons navigate the search process.

Improbable as it might seem, Four Wives Frank helped me understand the extent of Faith’s secrets and that she harbored them in hopes that her children’s lives would be easier. Such self-sacrifices are common for mothers. And yet, their particulars are as individual as the faintly silvered portrait of the soft young woman who married Harold Avery in 1911, and whose story requires an entire book to tell properly.

Andrea Kaston Tange does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.