As daylight hours shorten and temperatures drop, and with borders reopening across the Pacific, many will be tempted to escape pandemic fatigue by flying somewhere warm and welcoming.

Fiji, in particular, has wasted no time mounting a major campaign targeting New Zealand and Australian tourists. Fronted by celebrity Rebel Wilson, the ads promise the island nation is “open for happiness”.

Fiji is now averaging around 1,200 tourist arrivals each day. With quarantine requirements and other COVID restrictions recently removed, tourist numbers are expected to exceed 400,000 by the end of this year.

This will bring millions of much-needed dollars into a tourist economy hit hard by the pandemic. Many resorts have now re-opened, with around 50% of Fiji’s 120,000-strong tourism workforce having returned to work so far.

But behind the smiles and sunny marketing hype, how is Fiji really coping after such a challenging COVID experience?

Behind the smiles

When Pope John Paul II dubbed Fiji “the way the world should be” in 1986, he coined a tourist slogan that would last for years. But it hid some of the harsher realities of the country, including the ethnic and political fractures that led to a succession of coups.

These days, it’s estimated around 30% of the population lives in poverty. Crime has been increasing and there are ongoing concerns over the fragility of the health system.

Read more: Without stricter conditions, NZ should be in no hurry to reopen its border to cruise ships

As tourism resumes, COVID is still lingering, and there have been outbreaks of leptospirosis, typhoid and dengue fever, contributing to around 60 deaths since the start of the year.

Despite a strong vaccination drive that reached 90% of the eligible population, COVID took a high toll. Unlike Vanuatu and Samoa, whose borders are still closed to tourism, Fiji’s relatively relaxed approach had serious consequences. Medical experts suspect the official estimate of 862 deaths from the coronavirus is vastly under-reported.

Read more: As borders reopen, can New Zealand reset from high volume to ‘high values’ tourism?

Well-being during the pandemic

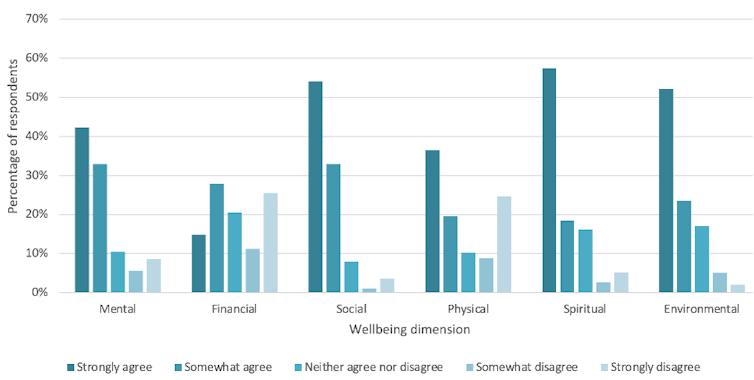

Given the hardships of the past two years, then, one might think that Fiji being “open for happiness” might apply to Fijians as well as tourists. But some recent research showed surprising results (see graph below).

The survey of people living in tourism-reliant communities, conducted just before the border opened in December 2021, found most people felt their mental, social, physical, spiritual and environmental well-being had actually improved during the pandemic when there were no international tourists. For many people, these things had “strongly improved”.

In the absence of tourism jobs, people had gone back to the land and sea to source food, and reconnected with their culture and kin. As two former tourism workers said:

I am now very close with my cousins and family because we spent time together catching food and planting. That is what life is about […] the pandemic gave me this time to be close with my community on a deeper level.

Things have been very positive for our village. We are now closer as clans… Especially for us youth to learn and know what we are supposed to do to care for each other – that’s the Fijian way!

Respondents also talked about improvements in the natural environment:

With no tourists around the lagoon, the reef and land has had time to relax and recover so that has been positive – to see fish come back.

Survey: well-being improved during the pandemic – agree or disagree?

Tourism that benefits hosts and guests?

Everyone enjoys a holiday, being pampered, enjoying new experiences and returning home relaxed. But can this be achieved in ways that benefit the Fijian economy while also supporting the well-being of the hosts?

Many New Zealand and Australian tourists report their interactions with the local people and culture were the most enjoyable aspect of their Fijian holidays. The 2019 visitor survey showed a key reason for choosing Fiji was that “the local people are friendly” – a close second to being a “family-friendly” destination.

Those qualities in the people and their culture were also the foundation of the adaptation and resilience that got them through the toughest times of the pandemic.

And while many businesses are eager to get back to the way things were, not all workers are sure they want to return to tourism jobs. Those who experienced greater well-being in the absence of tourists are looking for a more balanced approach that recognises the importance of health, family, culture and environment.

Tourists themselves can help, firstly by listening to the Fijian people’s own ideas about how best to reconfigure tourism to improve well-being, including a fairer deal for those working in resorts: a Fiji Trade Union Congress assessment of 2,132 workers during the pandemic found 99% wanted the government to do more to support labour rights and protect their jobs.

Tourists, too, can support local movements for better wages and conditions, job security, stronger unions and social insurance schemes. Ultimately, putting host well-being on the same page as guest well-being will give “open for happiness” a deeper meaning.

Apisalome Movono receives funding from Royal Society Te Apārangi under a Marsden Fast-Start Grant.

Regina Scheyvens receives funding from Royal Society Te Apārangi under a James Cook fellowship

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.