Some flocked to airports for long-delayed holidays or much-needed escape. Others flooded bars to reconnect with loved ones or had casual sex like it was going out of style. For almost two-and-a-half million of us, though, “normal” didn’t resume until we were sat in a bedroom at 9am, furiously refreshing the Glastonbury ticket website with RSI blighted fingers, Two tweets already drafted: one a screenshot of a check-out failing to complete, the other a picture of us gloating in a Billie Eilish face mask.

Live music and festivals returned almost a year ago, but Glastonbury 2022 will still be the major signifier that the post-pandemic party is back in full swing. As an event that, in any regular pre-Covid year, would see an avid scramble for the 200,000 tickets to one of the biggest and most head-spinning cultural events in the world, after two years away this will be a particularly emotional comeback. The festival equivalent of Noel Gallagher turning up at Liam’s house with a Union Jack guitar and a bowl of cornflakes sprinkled with cocaine.

For many music fans, Glastonbury represents the British summer. Without it, it feels like a musical hole has been punched through the heart of the cultural calendar. Each regular fallow year – one in every five to allow Worthy Farm and its neighbours to recover – leaves that festival season feeling subdued and bereft, ramping up anticipation for the next great blow-out chez Eavis. After two tedious years with barely a sniff of a psychedelic falafel, then, Glasto’s homesick regulars – such as myself, a veteran of over 20 Glastonburys and with the webbed toes to prove it – are as desperate to get back to the naked mud sauna as Nadine Dorries is to defend governmental criminality. That's even without the celebratory addition of Glastonbury's belated 50th birthday (the first event was in 1970). By comparison, the Jubilee will look like your cat’s lockdown snipaversary.

“It feels like its own world,” Billie Eilish says in a new BBC Two documentary to mark the event, Glastonbury: 50 Years & Counting. The Gen-Z pop star is a recent convert who successfully pinpoints why Glastonbury means so much to so many. The world-beating line-up virtually plays second fiddle to the hippie hoopla and rave surrealism that engulfs it. This is a place where you can be glugging suspiciously misty ciders to a Weimarian cabaret band in an underground piano bar one minute then, a short squelch across site later, be raving in a dystopian future society or basking in the flames spewing from a gigantic techno spider. Here, you can crawl through secret rabbit holes into hidden costume parties. Dance ’til dawn in a club designed like a dilapidated tower block with a train carriage crashed into the second floor. Plug yourself directly into the leyline at the on-site stone circle, or get gonged senseless by a guru in the Goddess Temple. Contrary to popular opinion, you don’t need drugs to get the most out of Glastonbury; Glastonbury is drugs.

Previous films about the festival have tried to capture this intangible vibe on camera – a fruitless endeavour that’s more likely to give the viewer an epileptic attack than a sense of what’s it’s really like to be there. The new documentary traces the history of the festival as a cultural bellwether. It covers its hippie early Seventies roots through to its embrace of indie rock and traveller culture in the 1980s, its part in cohering rave and Britpop, and its reflection today of the tribe-free inclusiveness of the streaming age.

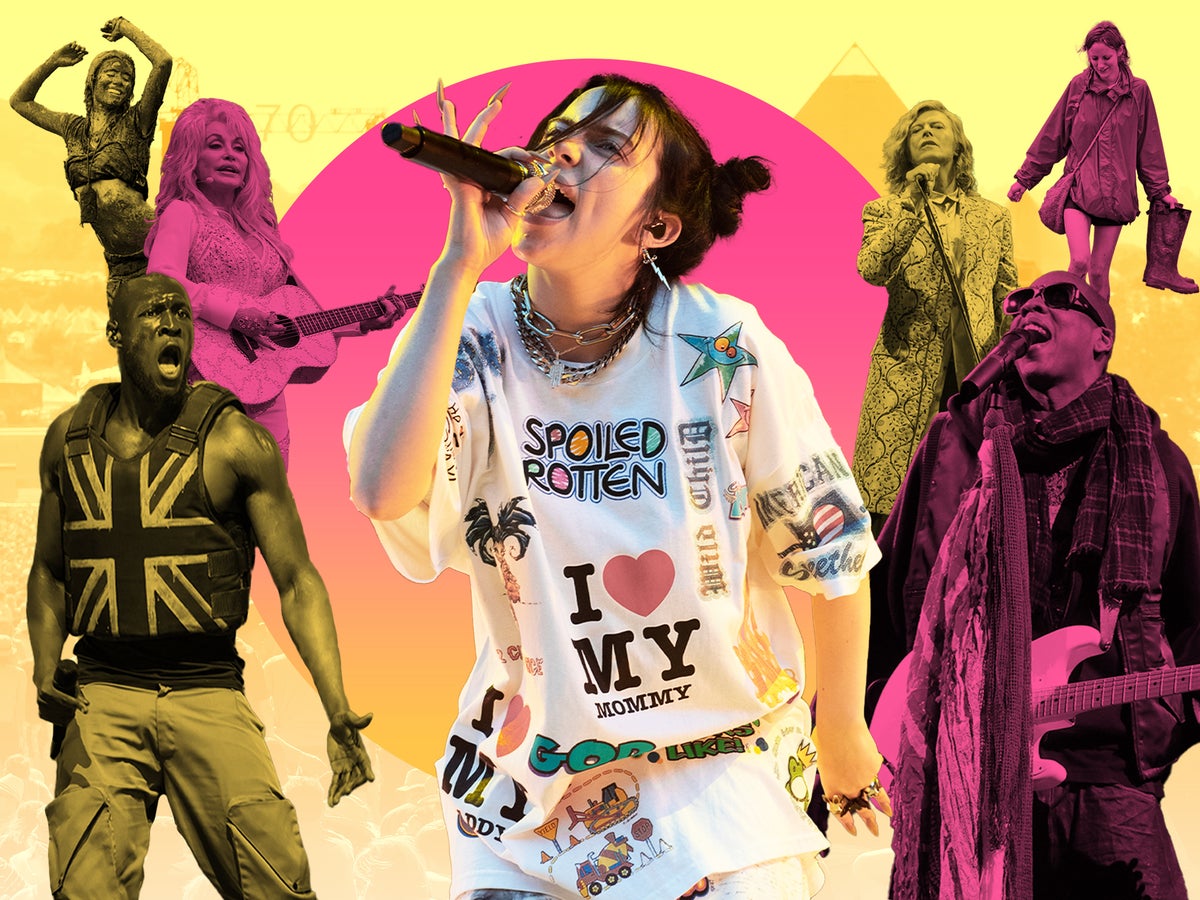

Along the way, a few key Glastonbury Moments are touched on; those sets that united generations, broke barriers and back-handed music into unexpected directions. Much is made, as usual, of the 1997 festival being so miserable thanks to bad weather and the impending turbo-Thatcherism of New Labour that Radiohead’s headline set encapsulated. But this was also where the hip-hop war of 2008 blew open alternative culture to all its rebel voices, at the moment Jay-Z strode onto the Pyramid stage with an acoustic guitar and sang a snippet of Oasis’ “Wonderwall” to prove that he had 99 problems, but Noel Gallagher’s outdated belief that rap had no place at Glastonbury certainly wasn’t one. It's where Stormzy similarly planted grime’s flag at the peak of British culture in 2019. “I feel my entire life has led to this moment,” he told the crowd. And, it seemed, the entire course of UK rap music too.

I feel my entire life has led to this moment— Stormzy, Glastonbury 2019

Glastonbury’s history-making moments are legion. Orbital bringing dance music to the main stages. Dolly Parton and Paul McCartney prompting singalongs that rattled the Tor. Pulp premiering “Sorted For E’s And Whizz” as show-stealing surprise headliners in 1995, replacing The Stone Roses. David Bowie returning 29 years after headlining the second Glastonbury to 12 hippies and a dog in 1971, finding it somewhat changed in his absence. This was the scene of Arctic Monkeys’ triumphant ascendence, of The Rolling Stones’ belated appearance and of Pussy Riot, in 2015, invading the Park Stage in a tank. But these are merely the tip of the experiential pyramid. As much as Glastonbury’s banner message is one of communal bonding, it’s the personal connections that are made at, and with, the festival that make it feel so much like a home – and occasional swamp – from home.

As a utopian pop-up city where hedonism and communal goodwill are expected norms, Glastonbury is responsible for life stories that can’t happen anywhere else. We all know someone who was conceived at Shangri-La or fell in a long drop. A friend told me this week of the time they jumped the fence in 2000 only for their gig-mate to slip and fall on the other side; the man who rushed to her aid became her husband a few years later. I’ll never forget sitting in the guest bar in the early hours, some time in the Noughties, asking every passer-by if they liked Weezer and, if they did, recruiting them into my impromptu Weezer and Wine Choir. If you’ve ever been, you’ve got your own personal legend to spin.

Glastonbury 2022, then, isn’t any mere mega-festival. It’s 200,000 people making a long-awaited pilgrimage back to their hallucinatory happy place, and pop culture’s most permeable looking glass hoisted high above the summer once more. If you can remember it, you’re probably watching it again on catch-up.