Chances are, someone somewhere in the world sits on a toilet or scrambles eggs, oblivious to the origins of the greenish-gray blob embedded in their limestone bathroom floor or kitchen counter.

They would likely not know that the golf-ball-sized blob was formed some 467 million years ago — long before the arrival of the first dinosaurs — during the most violent of cosmic collisions somewhere between Mars and Jupiter and that the chunk of rock to which they pay scant attention then fell to Earth, becoming buried in ocean sediment.

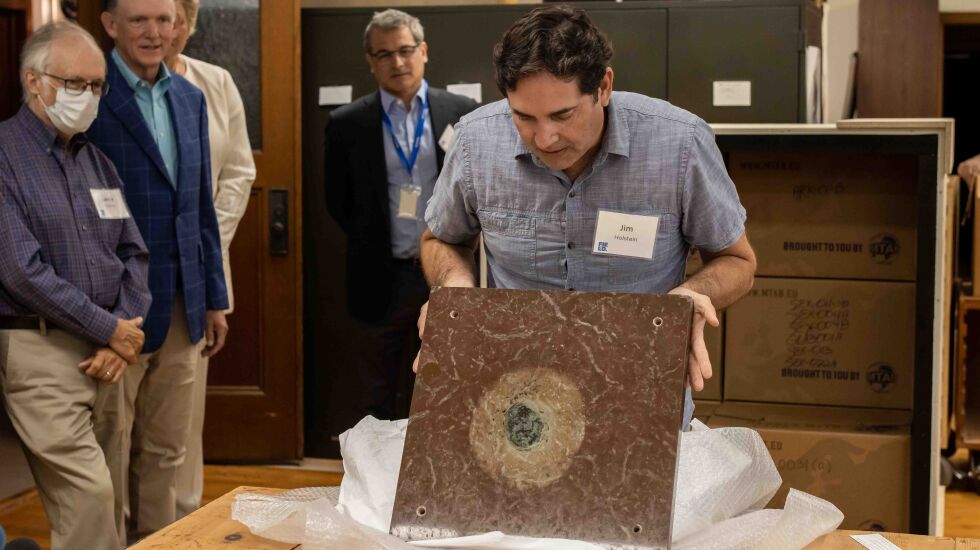

But Philipp Heck knows. The Field Museum curator of meteoritics and polar studies was as proud as a new dad Monday as he and his colleagues unpacked two giant crates filled with fossilized meteorites that originally came from a commercial limestone quarry in Sweden.

“Christmas!” said a beaming Heck, as the lid came off the front of a colossal wooden box — like something out of the crate-filled hall in the final scene of “Raiders of the Lost Ark.”

In all, the Field last month received 115 specimens, all of which came from the quarry and rained down on Earth.

Half a billion years ago or so — when the oceans were populated with trilobites and squid-like creatures with long, pointy shells — something smashed into an asteroid about 70 miles wide, which is about 10 times as large as the object believed to have wiped out the dinosaurs.

“Luckily, this collision happened far away from Earth,” Heck said.

Over the next 1 million years, debris and lots of dust rained down on Earth. Some of it ended up in what is now present-day Sweden, Heck said. The space rocks were buried in layers of sediment, preserving them.

“These meteorites were found by accident, and once they were recognized as such in the 1980s, the quarry workers were trained to spot them,” Heck said. “They put them aside.”

Before that, the polished limestone was used for everything from countertops to stair steps to church wall paneling, Heck said.

“If someone has them in their kitchen, I’m very happy for them. Maybe at some point, they will let us sample them,” Heck said. “Even if they don’t, we have a lot of material to work with.”

Heck described the new arrivals — gifted to the museum by longtime donors Terry and Gail Boudreaux — as “spectacular.” It’s perhaps a little harder to drum up the same kind of enthusiasm among museum visitors, who gravitate toward fossils with 6-inch-long teeth and flesh-shredding claws.

“The whole story needs to be told — the collision. We don’t have pictures of the collision, but the breakup event needs to be told,” Heck said. “The influence it had on Earth’s systems.”