The PlayStation has been a colossal consumer hit, but three decades ago, its creator Ken Kutaragi struggled to convince both game-makers and his bosses at Sony that his console would be a winner.

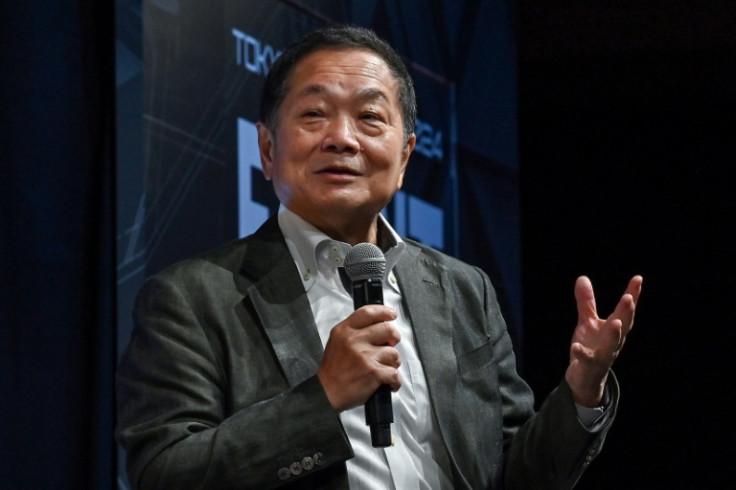

"Everyone told us we would fail," Kutaragi told AFP in a rare interview.

With revolutionary 3D graphics and grown-up titles like "Tomb Raider" and "Metal Gear Solid", the device first hit shelves on December 3, 1994.

Before that, Nintendo's NES console and similar gaming machines were considered "children's toys", the 74-year-old Kutaragi said.

Popular games like "Super Mario Bros" were two-dimensional, and computer-generated imagery (CGI) was a rarity even in Hollywood.

"Most of the executives (at Sony) were fiercely opposed," fearing for the Japanese giant's reputation as a producer of high-end electronics, Kutaragi said.

Japanese game-makers gave a "frosty response" too, as creating 3D games in real time seemed "unthinkable" at the time.

Films with CGI took one or two years to make in those days, with budgets of tens of millions of dollars, he said.

But Kutaragi, then a Sony employee, was not deterred.

"We wanted to make the most of technological progress to create a new form of entertainment," the engineer said, his eyes gleaming.

His ambition paid off: the console -- now in its fifth generation -- became a household name. The PlayStation 2 was the world's top-selling games console with 160 million units sold.

Sony and fellow Japanese game giant Nintendo are industry rivals, but more than three decades ago they worked together to make a CD-ROM reader compatible with the Super Nintendo console, which could only take game cartridges.

With Nintendo's permission, Sony was also developing a machine capable of reading both CDs and cartridges, with the working title "Play Station" -- the first time the famous name was used.

But the pair's bonhomie ended dramatically.

Hours after Sony unveiled its new project at a 1991 Las Vegas trade show, Nintendo, spooked by Sony's rights over the games, announced it would team up with Dutch firm Philips instead.

The episode was seen as a betrayal and humiliation for Sony, and all of these burgeoning projects failed to materialise.

"Newspapers said it was bad for us," Kutaragi said. But "it was inevitable that we and Nintendo would follow our own paths, because our approaches were totally different".

For Nintendo, "video games were toys that had nothing to do with technology," he said.

And without the snub, the PlayStation as we know it "would never have seen the light of day".

When Sony launched its PlayStation and CD games in Japan in 1994, and in Western countries some months later, Nintendo had a stranglehold on console sales.

So Sony used its experience in the music industry to develop a new distribution model, selling the gadgets at electronics stores instead of toy stores and creating new supply chains adapted to local markets.

Kutaragi eventually became vice president of Sony but left the conglomerate in 2007 after the launch of the PlayStation 3, which initially struggled commercially.

Now the future of the console market is less rosy as "cloud gaming" grows in popularity, something that Kutaragi also predicted -- along with mobile gaming years in advance.

"I'd often reflect on the future of technology, over 10 or 20 years, to predict new trends," although "many people found that hard to understand", he said.

The engineer now runs a start-up focused on robotics and artificial intelligence and teaches at a Japanese university.

"We are entering a world where everything can be calculated" by a computer with the help of AI, Kutaragi said.

For example, generative AI chatbot ChatGPT "exists because language has become computable", and similar technology is being used in sectors as diverse as medicine, music and visual art.

"Imagine if time and space were also computable," he said.

"For the moment, this is a possibility limited to the world of video games," but "imagine that we could move instantly to any place", Kutaragi said.

"What was once science fiction could become reality."