Most of the fossil fuel sources of methane, such as leaks from wells and pipelines, can be easily and cheaply fixed. But solving agricultural and food emissions is a much bigger task requiring much research and new technology

Opinion: New Zealand farmers have a great responsibility to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions, and they have beneficial ways of doing so, Simon Upton, Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment, laid out in a recent speech to an agricultural climate conference.

“And there is pure self-interest in this," he said. "We have an interest in continuing to sell products to high-income markets where consumers are taking an increasing interest in the emissions footprint of their food and drink. Being able to show that New Zealand products are associated with the lowest possible emissions will be essential if we are to continue to be a preferred supplier.”

READ MORE: * Farmers' self-interest should encourage climate mitigation, if nothing else * New research must be on regenerative farming, not methane inhibitors

His fully-evidenced speech is one of the most compelling arguments yet for the superior future farmers can make for themselves. And that’s even before including related biodiversity benefits which in turn will give their businesses greater ecological and economic resilience.

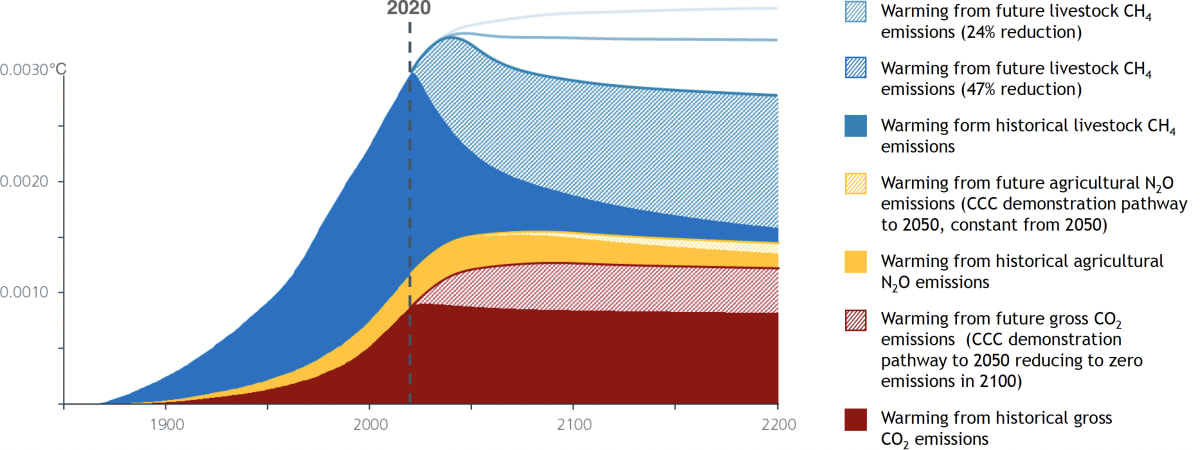

They’ll need all of that, as his most telling chart demonstrates below. This shows the substantial warming caused by our past emissions, and by those forecast. Note that this chart does not include the 18 billion tonnes of CO2 we released by clearing NZ forests for farming – roughly 10 times the amount we have ever emitted from burning fossil fuels, as Upton pointed out in his speech.

Warming from past and future emissions

Red are emissions of CO2, blue methane from livestock and yellow from agricultural nitrous oxide. All peak around 2050. The warming effect of these long-lived gases, CO2 and N20, essentially lasts for ever.

But the warming impact of methane, a shorter-lived gas, at its peak is considerably larger than of the other two gases. Worse, even if we make some reduction in methane emissions from ruminant animals but keep farming them, methane will still dominate out to 2200, the end point of the chart, and beyond.

Thus, methane continues to be our largest source of warming in perpetuity – unless we achieve the desirable state of zero-methane animals. That’s the challenge farmers must rise to. If they accept that responsibility to work towards zero-methane animals, they can be sure of lots of support from government and many consumers.

READ MORE:

* Surprise! Farmers can be the new heroes of climate mitigation

* Let’s hope we respond to these sudden shocks by ditching short-termism

* NZ’s farmers’ global customers demand more rigorous climate response

Upton’s speech was timely. Around the world, agriculture and food are attracting ever greater scrutiny as key drivers of climate change. For example, this week Nature Climate Change, a peer-reviewed journal, published a paper on food’s climate impact.

The authors concluded that if the world’s food systems continued unchanged, they will cause 0.7C of additional warming by 2100, pushing the planet past the 1.5C threshold set by the Paris Agreement, even if fossil fuel use is drastically reduced.

"I think the biggest takeaway that I would want to have is the fact that methane emissions are really dominating the future warming associated with the food sector." – Catherine Ivanovich, Columbia University

The authors analysed emissions from nearly 100 types of food and ran the data, along with estimates for population growth in the coming years, in a climate model frequently used by the United Nations for its global warming projections. The analysis found that production of meat accounted for 42 percent of agricultural emissions, rice 23 percent and dairy 19 percent.

“I think the biggest takeaway that I would want [policymakers] to have is the fact that methane emissions are really dominating the future warming associated with the food sector,” said Catherine Ivanovich, a climate scientist at Columbia University and the study’s lead author.

Moreover agricultural methane accounts for 40 percent of all human-induced methane emissions, with fossil fuels accounting for a similar share and the other 20 percent coming from rotting waste (natural, and human-sourced).

Most of the fossil fuel sources of methane, such as leaks from wells and pipelines, can be easily and inexpensively fixed. But solving agricultural and food emissions is a much bigger task requiring much research and new technology.

"When it comes to agricultural emissions, who are we waiting to follow? We have more skin in this game than others. We have serious research capacity ... We have to tackle this problem head on.” – Simon Upton, Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment

As Upton noted in his speech, some New Zealand farmers argue they only need to achieve a minor reduction in methane emissions to show their warming impact is flat-lining.

But that ploy won’t work, he said. “Under the Paris Agreement, New Zealand has an international obligation to do as much as it can to keep the 1.5C global goal within reach. It is not a credible negotiating position to say that our largest contribution to warming is off limits when we have the option to reduce it.

“Neither, by the way, is it credible to say that global mitigation has failed so we may as well just get on with adapting. A 3C-4C warmer world won’t be a very happy place for agriculture. As a little country we need to argue hard for international action, and we have no credibility if we seek a leave pass for our largest contributor.

“Neither should we be tempted by the argument that since we’re a little country it doesn’t make sense for us to develop the technologies needed to solve the world’s problems and that we should instead be a fast follower. That might be true of concrete or steel but when it comes to agricultural emissions, who are we waiting to follow? We have more skin in this game than others. We have serious research capacity. We have long congratulated ourselves on our productivity and resourcefulness. The logic all leads to the conclusion that we have to tackle this problem head on.”

Our current national goal for reducing methane is a 10 percent cut by 2030 from 2017 levels; and a 24-27 percent cut by 2050. Upton said we can achieve both through two broad strategies:

* Reducing livestock numbers, through lower stocking rates per hectare and land use change.

* Reducing emissions per animal, through changes in management practices and the uptake of new on-farm mitigation technologies as they become available.

He said dairy farmers can likely achieve a 10 percent cut in emissions by using existing management techniques such as keeping livestock off pasture at sensitive times, once-a-day milking, improved effluent management, low-nitrogen feeds and reducing nitrogen fertiliser use. However, their practicality and impact on profitability varies from farm to farm. Moreover, sheep and beef farmers have fewer options.

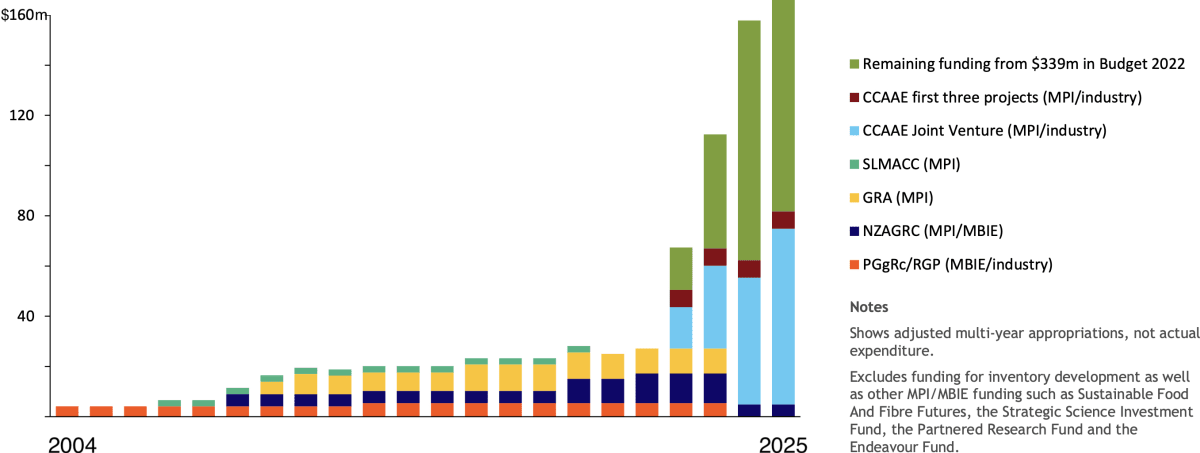

Achieving bigger reductions requires substantial investment in research and development. At the Copenhagen climate summit in 2019 New Zealand advocated establishing the Global Research Alliance on Agricultural Greenhouse Gases. But in the following decade our Government only funded $20 million a year of such research – a pittance for a sector generating $24 billion a year in export revenues.

Funding for agricultural greenhouse gas mitigation research

Then finally in Budget 2022, the current government added an additional $340m over four years. “It’s worth noting that since this initiative is funded from the Climate Emergency Response Fund, it is effectively being paid for by the fossil fuel emitting sector of the economy,” Upton said in his speech. In addition, agribusinesses have committed to spend at least $35m per year by 2025.

“It is well overdue. What a pity that we didn’t take the challenge more seriously two decades ago.”

Rod Oram will be taking a three-week break and his column will resume on Friday April 7.