Freshwater turtles live in farm dams, creeks and wetlands across Australia. They often travel over land when these wetlands or farm dams dry up, or during breeding season.

But when a turtle encounters a fence, they can get stuck on one side, become entangled, overheat or even die.

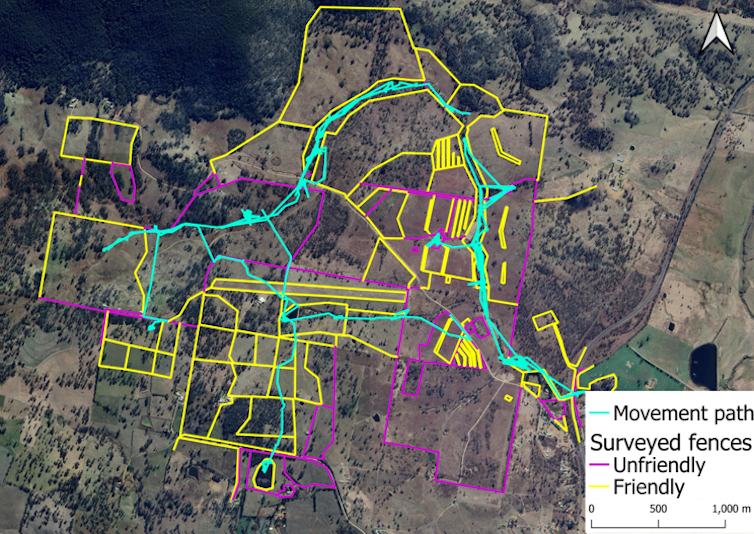

We wanted to test how different fence types influence turtle movement patterns. In our latest research, we attached GPS tracking devices to 20 adult eastern long-neck turtles in Armidale, New South Wales. Each week, we located the turtles and recorded how far they had moved, what habitat they were in, and how many fences they had encountered.

We found turtles often encountered fences. Sometimes they had to walk long distances, for days, before finding a suitable place to cross. Here we recommend some simple, cheap ways to make fences more turtle-friendly – and help other wildlife too.

Active in agricultural lands

The eastern long-neck turtle is one of Australia’s most widespread turtle species, but populations may be in decline. As a result, their conservation status could soon be upgraded to “vulnerable”.

Its range includes the Murray-Darling, Australia’s longest river system and most intensive agricultural area.

Long-neck turtles are also among the most active turtles on land, often travelling kilometres to find water. So they frequently encounter fences.

We found all sorts of farm fences in our 1,000 hectare study area, stretching over 95km in total. Fencing materials included:

- plain or barbed wire

- “hinge joint” wire (grid pattern)

- single-strand electric wire

- chicken wire

- corrugated iron.

We classified the different types of fences as turtle-friendly, or not. In turtle-friendly fences, the mesh or wire spacing is greater than the body size of the turtle. Unfriendly fences, in contrast, have mesh or wire spacing smaller than turtle, barring their passage.

Our turtles encountered fences 120 times in the ten months of the study, from November 2022 to September 2023. Most of the time they managed to get through. But in some cases, turtles had to walk up to four times further before finding a suitable gap or fault in the fence.

Some fences at our study site were damaged. Broken wire, gaps or holes from fallen trees or burrowing wildlife actually turned an unfriendly fence into a turtle-friendly fence. So turtles were able to walk along the fence and locate a suitable gap or fault that allowed them to cross.

However, this meant turtles had to walk up to four times further along unfriendly fences before finding suitable passage. Turtles were walking an additional 1,000 metres over the course of nine days in some cases.

The search for a gap or hole potentially exposed turtles to predators, excessive heat and dehydration.

In Armidale, adult eastern long-neck turtles are smaller than in other parts of its range. This means they fit through fences more easily than larger eastern long-necks from other regions, or other larger turtle species.

So, while turtle-friendly fences were abundant in our study, many of these would have been unfriendly fences for larger turtles living elsewhere.

How to make farm fences more wildlife-friendly

Replacing millions of kilometres of farm fencing around the world is not feasible, so we recommend a range of targeted and realistic tactics.

Species-specific wildlife gates allow wildlife such as bettongs and wombats to travel in and out of fenced areas. These gates can be installed in places where wildlife are most likely to encounter fences, such as wildlife corridors, rather than randomly throughout a property.

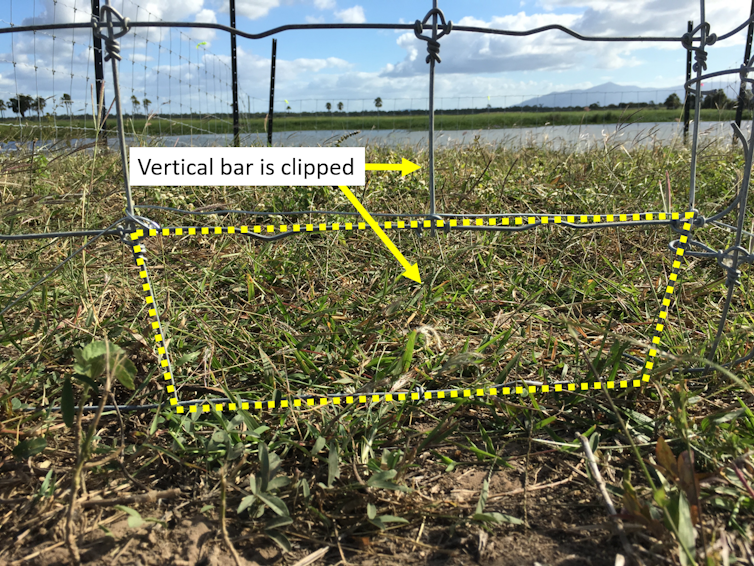

Other strategies are more simple and cost effective, such as clipping one vertical bar of hinge joint fencing to make the mesh gap twice as large. This creates a “turtle gate” that allows larger turtle species to move through the fence.

Similarly, ensuring the bottom of the fence is at least 50mm above the ground can help facilitate movement by small animals.

Where possible, chicken wire style fencing should be avoided because the mesh diameter is too small to allow turtles and many other wildlife species to pass through.

For more tips on building your own turtle-friendly fence and information on other turtle projects, check out our downloadable fencing brochure.

Reducing the harm of fences

Although fences are useful for managing livestock, protecting crops and keeping out predators, they can have unintentional and harmful effects on other species such as turtles.

Fence design, location and upkeep should be more carefully considered, with wildlife in mind.

Eco-friendly fence designs (for turtles, mammals, or any other wildlife) should be used whenever possible, to help wildlife travel through their now-fragmented habitat.

Eric Nordberg is affiliated with the University of New England and receives external grant funding through NSW, SA, and QLD governments.

Deborah Bower works for the University of New England. She receives funding from the Australian Research Council, NSW, SA, QLD and Commonwealth Governments.

James Dowling is affiliated with The University of New England and The Ohio State University. He receives no external funding directly.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.