Singapore is set to resume executions for the first time in six months on Wednesday, with a 46-year-old man facing the gallows in a case that has reignited criticism of the city-state’s use of the death penalty.

Singaporean national Tangaraju Suppiah was sentenced to death in 2018 for abetting the attempted trafficking of just more than a kilogram (1,017.9 grams) of cannabis. A judge found that he was using a phone number that was communicating with traffickers who were attempting to smuggle the drugs into Singapore.

Tangaraju’s family and anti-death penalty campaigners have attacked the authorities’ handling of the case, claiming that the defendant was not provided with adequate legal counsel.

They also say that Tangaraju was denied access to a Tamil interpreter while he was being questioned by the police.

“Tangaraju said his English is not that good, he wanted an interpreter but he couldn’t get one. Then he’s really disadvantaged because if he can’t properly understand the police statement that was read back to him, how could he make any amendments?” activist Kirsten Han told Al Jazeera.

“It really disadvantages people who might not have the language skills or the education level to advocate for themselves in that situation when they don’t have lawyers who are looking out for their interests.”

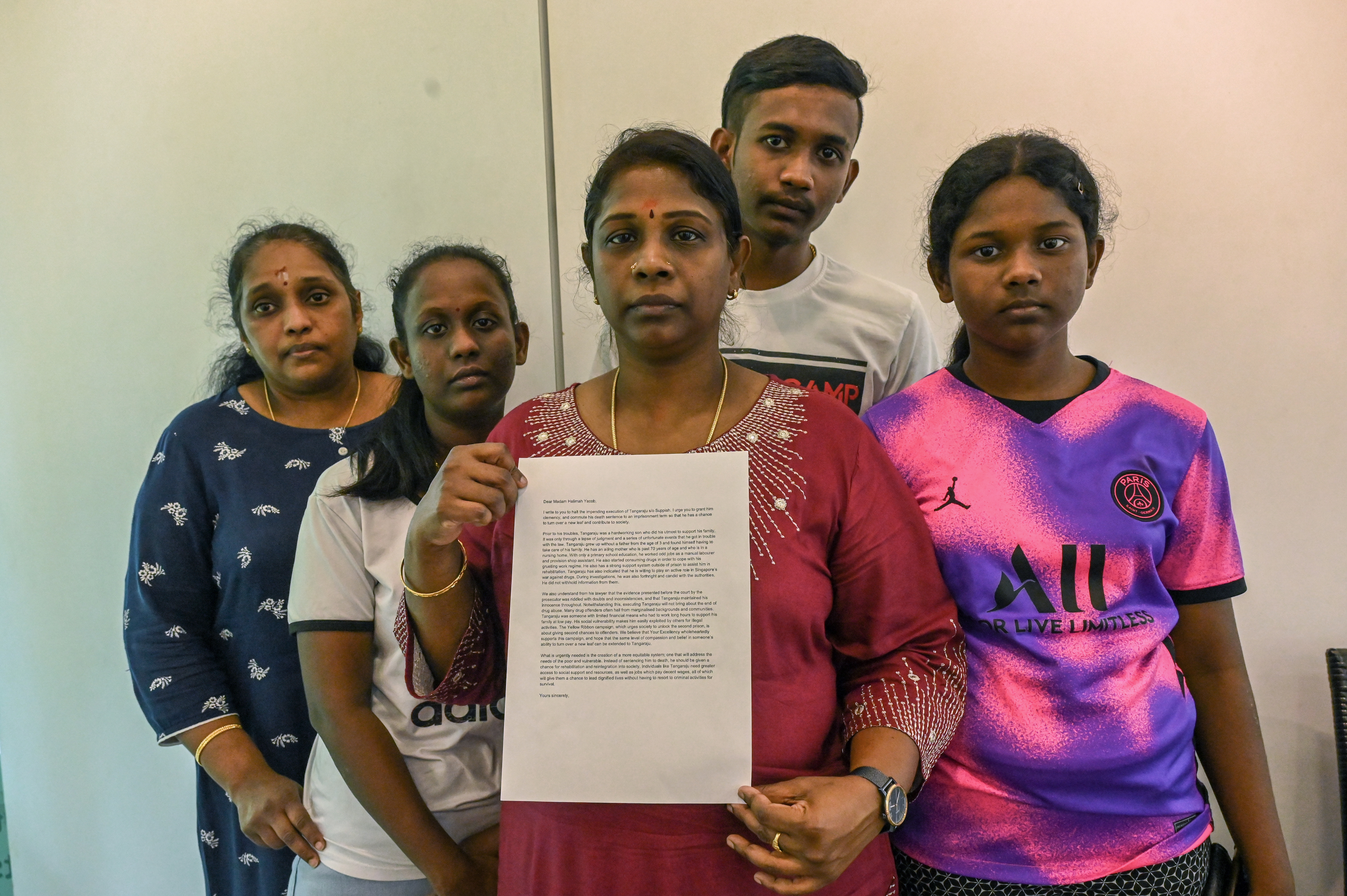

Tangaraju’s family have desperately tried to halt the impending execution, delivering dozens of letters to Singapore’s President Halimah Yacob, asking her for clemency.

They have yet to receive a response from the president or her staff.

Prominent campaigners, including British billionaire Richard Branson, have also pleaded for the execution to be halted.

But as the clock ticks down towards the scheduled hanging on Wednesday, the authorities appear unwilling to listen to any last-ditch appeals.

“They took his height and weight to measure the rope for the execution,” Tangaraju’s sister Leelavathy told Al Jazeera.

“He told us that he will be taken to visit the execution chamber, so that they can explain to him how things will happen and where he will be standing and things like that. That was obviously very difficult to listen to.”

With his execution potentially just a matter of hours away, Leelavathy says her brother remains “confident that there will be justice” and is “in good spirits”.

‘Fair trial concerns’

Tangaraju was first detained by police in 2014 for drug consumption and failing to report for a urine test.

Leelavathy says he started using drugs after being offered them by older friends in his neighbourhood.

“He was never given any support or tools to understand or cope with his habits or find any help for his dependence on drugs,” she said.

“He’s never received counselling or therapy, or even education about drugs. He’s only been punished his whole life.”

While on remand in 2014, police investigated Tangaraju for suspected links to a cannabis trafficking case from the previous year involving two smugglers.

“He was not arrested with the drugs, he was not even on the scene. He was basically tied to this case after the fact — they arrested those two other guys in September 2013,” said Han.

Those caught with the drugs were not charged with capital crimes.

Tangaraju was eventually found guilty of conspiring to traffic cannabis after the court ruled that he was linked to the traffickers through a phone number that the prosecution said belonged to him.

He appealed his conviction in 2019 but the case was dismissed by Singapore’s Court of Appeal.

Tangaraju unsuccessfully filed an application for his case to be reviewed late last year. He had to represent himself in court as he could not find a lawyer to take on his case.

“Access to counsel has to start from the moment a police investigation is commenced until the moment a person has been escorted to the gallows,” said Sara Kowal, vice president of the Capital Punishment Justice Project.

“We have real fair trial concerns in this case, in terms of access to counsel, access to interpreters, and just even the nature of the charge itself.

“If you’re going to have the death penalty, you also have to have the highest standard of fair trial rights and not be afraid of extreme rigour and review being applied to it,” Kowal told Al Jazeera.

The United Nations has said those countries that do retain the death penalty should use it only for the “most serious” of crimes, and drug offences do not meet that threshold.

In an online statement, Singapore’s Central Narcotics Bureau said: “Tangaraju was accorded full due process under the law, and had access to legal counsel throughout the process.”

Tangaraju’s hanging is set to be the first in Singapore this year. Local campaign group the Transformative Justice Collective says the country hanged 11 people for drug offences in 2022.

One of those killed was Malaysian national Nagaenthran Dharmalingam, with his case attracting international attention after he was found to have an IQ of 69, suggesting an intellectual disability.

Singapore’s unwavering commitment to its zero-tolerance stance on drugs is in stark contrast to some nearby countries that have eased policies around drugs.

Last year, Thailand removed cannabis from its banned list of narcotics, legalising the growing and possession of the drug.

Earlier this month, Malaysian legislators approved legal reforms to abolish the mandatory death penalty for serious offences, including drug trafficking.

Singapore, however, shows no sign of letting up. Minister for Home Affairs and the Minister for Law, K Shanmugam, explained the reasoning for his country’s tough drug rules to Malaysian media last year.

“If we are not tough in Singapore, we would be flooded with drugs. Look at the countries in the region and the impact of drugs on them. You don’t even need to guess what the result would be, if we are not tough,” he said.

But as Tangaraju sits down for his final meal ahead of his execution at Changi Prison, campaigners like Han maintain that Singapore’s hardline drug policies have done little to tackle the root of the problem.

“It just shows that the focus is really on punishment and delivering pain. It’s not about harm — it’s not looking at harm and who is harmed by this? And how do we keep people safe?

“It’s just punishment. Anyone who’s involved or linked to drugs in any way needs to be punished. That’s the overriding principle of Singapore’s war on drugs.”