We’re halfway through the federal election campaign, and by now you’ve probably seen a significant amount of political advertising – much of it online.

Online political advertising is more pervasive than its analogue predecessors, it can cost less (per individual ad), be deployed more rapidly, and can be micro-targeted towards specific audiences. The targeting can be aimed at protected social categories such as race and gender, and has been used to amplify mis- and disinformation.

Unlike billboards or TV ads which can be widely seen, targeted ads may be invisible beyond their intended audience. Researchers like us try to get a handle on online advertising through projects like the Australian Ad Observatory.

Here’s what we know so far about the state of online advertising in the federal election.

Dashboards

The big dogs in the online advertising world are Meta and Google. Meta allows advertising across its products including Facebook, Messenger, Instagram, and WhatsApp. Google allows ads in its search products, YouTube, and on Android.

Both companies have ad transparency dashboards. (Here is Meta’s, and here is Google’s.)

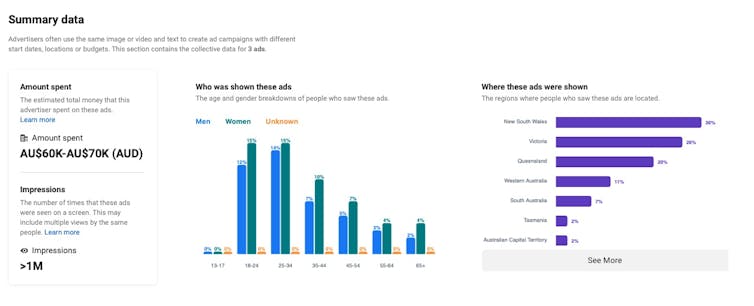

The dashboards detail the ads that are running, who is running them, and some basic aggregate data on targeting by geography, gender, and age.

For example, we can see the Australian Electoral Commission has spent around $383,000 on Facebook advertising in the past month, largely promoting election-related facts and voter registration information.

However, these tools are quite basic, and don’t offer all the information on how ads are targeted, nor insights into trends and patterns. To fill the void, researchers and journalists have been building their own.

For Facebook, we have partnered with colleagues at Ryerson University in Canada to extend their PoliDashboard to Australia. Colleagues at The University of Queensland have also released an excellent Facebook ad spend tracker.

For Google, The Guardian Australia has released data visualisations extending Google’s transparency dashboard with more useful data aggregation and geo-visual elements.

So what have we seen so far in this campaign?

Facebook focus

Analysing spending data from April 1 2022 onward, we can already see differences in how particular parties are strategically purchasing ads on platforms like Facebook.

In the lower house, the traditional Liberal stronghold of Kooyong has been an early standout. Polling suggests the incumbent, Treasurer Josh Frydenberg, is under threat from “teal” independent Dr Monique Ryan.

Read more: View from The Hill: Warring within Coalition over 2050 target brings some gold dust for 'teals'

Since the start of April Frydenberg has tipped around $80,000 into Facebook advertising in his own seat, while Ryan has spent around $41,000. Altogether, more than twice as much has been spent in Kooyong as in the next highest spending seats of Maribyrnong, North Sydney, and Wentworth.

In the senate, Queensland has so far attracted the most spending at around $110,000. Here, a rogues’ gallery of former LNP and other far-right candidates are scrambling to win one of the two seats that are likely to be up for grabs.

Beyond Facebook

We have also seen significant spending from political parties and registered organisations on Google ads. The total amount has been $17.7 million since 15 November 2021, of which United Australia Party’s ads account for a whopping $15 million, which includes many YouTube ads.

Over the past two years, Google has also introduced more advertising products and services in Android mobile games.

Ads in this gaming ecosystem are very difficult to track. The Google transparency dashboard doens’t include data that enables us to determine which ads appear in this specific ecosystem. However, users of our Ad Observatory have sent us photos and screenshots of UAP ads appearing within their mobile games. It seems some of that $15 million is finding its way into mobile in-game advertising.

Perhaps the most creative use of online advertising so far has come from Stephen Bates, the Greens candidate for Brisbane. Bates took out a series of ads on Grindr, a social networking and dating app for gay, bi, trans, and queer people, and men who have sex with men.

Bates’ tongue-in-cheek ads have slogans like “Spice up Canberra with a third” and “The best parliaments are hung”. Unlike other sometimes cringe-worthy attempts by politicians to appeal to specific communities, Bates has leaned into his own identity as an openly gay candidate in selecting this platform and developing ads using Grindr’s platform-specific vernacular.

What about Twitter, TikTok and the other big platforms?

Meanwhile, if you spend your time on Twitter or TikTok you won’t see any political advertising during this campaign.

Why not? It’s complicated, but it mainly goes back to the Cambridge Analytica scandal of the mid 2010s, in which personal profile data of more than 50 million Facebook users was siphoned from the platform and used to build a profiling tool that was then leveraged for political gain.

Mass-scale online ad microtargeting using this tool may have played a significant role in the success of Donald Trump’s 2016 US presidential campaign and the Brexit “leave” campaign the same year.

These events thrust online political advertising into the spotlight. In its wake lawmakers and civil society groups around the globe have steadily ramped up pressure on the platforms regarding online political advertising.

Read more: Twitter is banning political ads – but the real battle for democracy is with Facebook and Google

In response, Twitter and TikTok have decided political ads aren’t worth the trouble, and banned them outright.

Facebook instead shut access to third-party data gathering – which had the side effect of making genuine, ethical scholarly research more difficult.

Does any of this work, though?

Online political advertising is but one part of an overall campaign, but it can be used to tip the balance in one party’s favour.

In other countries, online advertising may focus on encouraging supporters to vote and discouraging opponents. However, Australia’s compulsory voting means campaigns are likely to focus on persuading a relatively small number of swinging voters. This in turn means specific highly contested seats (such as Kooyong) may play an amplified role within our elections.

One thing to watch in this election and beyond are the growing calls for truth in political advertising. Online election advertising will only become more intense, so we will need ways to reign in mis- and disinformation.

Daniel Angus receives funding from Australian Research Council through Discovery Projects DP200100519 ‘Using machine vision to explore Instagram’s everyday promotional cultures’, DP200101317 ‘Evaluating the Challenge of ‘Fake News’ and Other Malinformation’, and Linkage Project LP190101051 'Young Australians and the Promotion of Alcohol on Social Media'. He is an Associate Investigator with the ARC Centre of Excellence for Automated Decision Making & Society, CE200100005.

Axel Bruns receives funding from the Australian Research Council through Discovery project DP200101317 Evaluating the Challenge of ‘Fake News’ and Other Malinformation, Laureate Fellowship FL210100051 Dynamics of Partisanship and Polarisation in Online Public Debate, and the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Automated Decision-Making and Society (ADM+S).

Ehsan Dehghan receives funding from the Digital Society Project, for a project to create a dataset of candidates in the 2022 Australian federal elections

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.