Editor's note: This story was originally published on June 5, 2023 date, and was updated at 5:15 p.m. EDT on March 28, 2025, to add information from a newly published study.

Homo naledi, an extinct relative of modern humans whose brain was one-third the size of ours, buried their dead and engraved cave walls about 250,000 years ago, according to new research.

The findings are overturning long-held theories that only modern humans and our Neanderthal cousins could do these complex activities.

Evidence of burial practices in this early hominin would be a "landmark finding," according to a team of researchers who published their hypothesis in the journal eLife in 2023. But their theory became controversial, with numerous experts saying the evidence wasn't enough to conclude that H. naledi buried or memorialized their dead.

In a revised study published Friday (March 28) in eLife, the researchers laid out 250 pages' worth of proof of purposeful burial that they say has convinced more people.

Archaeologists first discovered the remains of H. naledi in South Africa's Rising Star cave system in 2013. Since then, over 1,500 bones from multiple individuals have been found throughout the 2.5-mile-long (4 kilometers) system.

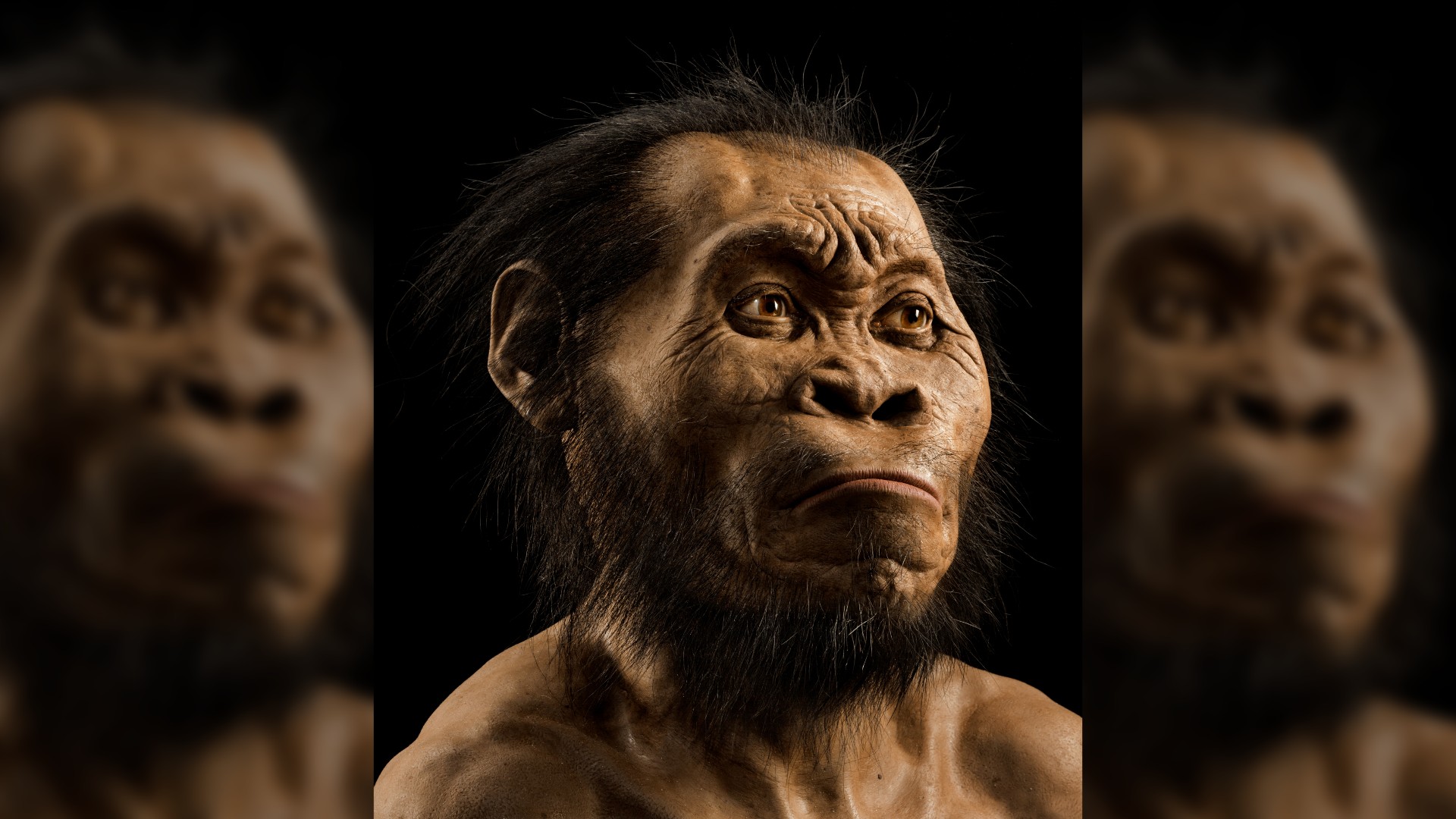

The anatomy of H. naledi is well known due to the remarkable preservation of the remains. They were bipedal, stood around 5 feet (1.5 meters) tall and weighed about 100 pounds (45 kilograms). They had dexterous hands and small-but-complex brains — traits that have led to a debate about the complexity of their behavior.

In a 2017 study published in the journal eLife, the Rising Star team first suggested that H. naledi had purposefully buried their dead in the cave system. And then, in a news conference in 2023, paleoanthropologist Lee Berger, the Rising Star program lead, and his colleagues buttressed that claim with three studies, published on the preprint server bioRxiv, that together put forth the most substantial evidence so far that H. naledi purposefully buried their dead and created meaningful engravings on the rock above the burials.

The research studies described two shallow, oval-shaped pits on the floor of one cave chamber that contained skeletal remains consistent with the burial of fleshed bodies that were covered in sediment and that then decomposed. One of the burials may have even included a grave offering; a single stone artifact was found in close contact with the hand and wrist bones.

At the 2023 news conference, Berger said "we feel that they've met the litmus test of human burials or archaic human burials." But many experts did not buy the researchers' interpretations, which would push back the earliest evidence of purposeful burial by 100,000 years, a record previously held by Homo sapiens.

"I can see where they are connecting the dots with this data and do think it was worth reporting, but it should have been done with many more caveats," Sheela Athreya, an anthropologist at Texas A&M University who was not involved with the research, told Live Science in a 2023 email.

In response, Rising Star team members have been collecting additional evidence to support their claim of purposeful burial, which they published — along with new peer reviews — in eLife. These changes included adding a comprehensive reconstruction of how the H. naledi bodies wound up in the cave system, including a timeline ranging from death to decomposition.

One expert, who had reviewed the 2023 study and declared it inconclusive, reviewed the new study and wrote, "I now think that the authors provide sufficient evidence for the presence of 'repeated and patterned' deliberate burials" by H. naledi.

However, a second reviewer wrote that the new paper remains unconvincing, noting that although "the world cares deeply about the H. naledi hominins and their story," it would be beneficial for other, independent teams to undertake a full analysis, "since science is about replication."

To date, the two other H. naledi preprints Berger's team released in 2023 have not been fully revised.

Controversial evidence of culture

One 2023 study suggested that the discovery of abstract engravings on the rock walls of the Rising Star cave system also signaled that H. naledi had complex behavior. These lines, shapes and "hashtag"-like figures appear to have been made on specially prepared surfaces created by H. naledi individuals, who sanded the rock prior to engraving it with a stone tool. The line depth, composition and order suggested that they were purposefully made rather than naturally formed.

"There are burials of this species directly below these [engravings]," Berger said, which suggests this was an H. naledi cultural space. "They've intensely altered this space across kilometers of underground cave systems."

In another preprint, which has not yet been published, Agustín Fuentes, an anthropologist at Princeton University, and colleagues explored why H. naledi used the cave system.

"The shared and planned deposition of several bodies in the Rising Star system" and the engravings are evidence that these individuals had a shared set of beliefs or assumptions surrounding death and may have memorialized the dead — "something one would term 'shared grief' in contemporary humans," they wrote.

Other researchers, however, are not fully convinced by those interpretations.

"They are also hard to prove as being intentional or forms of abstract thinking," Athreya said in 2023.

There are also questions about how H. naledi got into the Rising Star cave system; the assumption that it was difficult underlies many of the researchers' interpretations of meaningful behavior.

"Did they get in there the same way that we are getting in there, or might there have been another way in?" Jonathan Marks, an anthropologist at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte who was not involved in the research, told Live Science in 2023. "This is a job for archaeology — lots of archaeology."