Formed in Austin, Texas, Explosions in the Sky have built a loyal following over the past 25 years. The band, consisting of drummer Chris Hrasky and guitarists Michael James, Munaf Rayani and Mark Smith, have been acclaimed beyond the post-rock scene for their elaborate guitar work and catalogue of dynamic, narratively‑styled albums.

Perhaps unusually for an instrumental four-piece, their cathartic, emotive-led sound has seen them open for bands such Nine Inch Nails, Fugazi and Godspeed You! Black Emperor amidst invitations to score for numerous film and TV projects, with dozens of tracks licensed for commercials and even video games.

The collective’s latest album, titled End, has caused inevitable consternation amongst their fan base, forcing Explosions in the Sky to reject rumours of their impending demise. Instead, the LP is touted as their most grandiose to date; brooding, restrained and melancholy, yet uplifted by their trademark sonic crescendos.

Can you remember how you got signed by Temporary Residence – the label you’re still on 20 years later?

“Some friends of ours from an amazing band out of Austin called the The American Analog Set recorded one of our early live shows and sent the recording to the label. They liked it a lot, called us up and asked if we wanted to put a record out and we’ve been with them ever since – at least in the US. We’ve had other offers through the years, but we don’t want to have to deal with the bureaucracy of bigger labels so we’ve stuck with Temporary Residence and it’s been great.”

People often describe Explosions in the Sky as a post-rock band, whereas you’d rather be known as straight-up rock. Do you feel there’s a disparity in how you’re perceived?

“We’re probably called post-rock because the songs are long and instrumental, and that’s fine, but even though our songs are pretty crazy and different to typical rock, that’s the music that we all grew up on. We still think of ourselves as a bunch of friends with guitars and drums playing loud rock music.

“Even if the songs are long and excessive in some ways, we want the music to have immediacy and be, for lack of a better term, hummable. We’ve always approached the music as songwriters rather than soundscape artists, which is probably more applicable to the post-rock tag.”

Did the band ever think about employing a vocalist?

“We never really thought about it. When we formed we were heavily into two or three instrumental bands that were very important to us because their music was so emotionally charged and visceral. We wanted to emulate and pursue that route and never thought Explosions in the Sky would still be going 24 years later. Things seem to have worked out without the need for vocals, so the question’s never really come up in a serious way – it would create a completely different dynamic in the band.”

Your third album The Earth is Not a Cold Dead Place was unilaterally described as a concept album. By the very nature of your music, aren’t all your albums conceptual?

“We like to think that each song has its only little narrative arc that flows like a story, but specific concepts are very vague to us. We like the idea of writing songs that people can adapt to their own life circumstances – soundtracking their lives without them being told what a song’s supposed to mean.

“We’ve also always had this notion of wanting to write self-contained instrumental music that doesn’t feel like it’s in the background. It sounds silly, but a bit like pop music we want it to be immediate and memorable and not something you just zone out to. But that’s hard to do, and probably why the whole process takes us so long.”

Was there a particular reason for the seven year delay between this LP and your last one, The Wilderness?

“We toured The Wilderness for a couple of years and did a 20th anniversary tour 12 months after that. When that ended, the pandemic hit. The four of us are scattered across the country and in the first year of Covid none of us felt particularly creative or excited. It was more about… well let’s see how this turns out. We did work on a soundtrack during that period and when that finished we slowly started putting music together for this record.

“Being so distant from each other means that everything takes longer – there’s lots of file sharing and every couple of months we get together to work on stuff. It seems like the longer we’ve been a band, the longer it takes us to write songs, and part of that’s because we’ve got a little more self-critical. As you build a catalogue you don’t want to repeat things or make something feel any lesser and we don’t write on tour either.”

In general, bands do seem to take much longer to make music. Do you think that’s because there’s less financial incentive than there was 20 or 30 years ago?

“When you think about The Beatles, they weren’t really around for that long but look how much stuff they put out? I don’t really have an answer for that – maybe there was just a lot more cocaine back then. As you get older, people have families and kids and the constant focus on music blurs as other priorities come in, but I’m sure there was a bigger push from labels back then.

“At least for us, touring is where the bulk of our income comes from – for us to maintain this as a career we have to tour for a couple of years to keep ourselves funded. Playing live is such a big part of what we do.”

You’ve done a lot of soundtrack work throughout your career. Are those projects much different to how you might write traditional Explosions in the Sky songs?

“It’s completely different, but much easier for a number of reasons. First, there’s a deadline that a score has to be done by and you also have a guide, story, image or scene to write to. We have to make music that supports and accentuates that and a director or music supervisor is always there to tell us if something doesn’t work or that we should lean further into a particular direction. With soundtracks there’s a roadmap, but with our own records we just start from scratch with no real idea of where we’re heading.

When you think about The Beatles, they weren’t really around for that long but look how much stuff they put out? I don’t really have an answer for that – maybe there was just a lot more cocaine back then

“Soundtracks are also often background music. You don’t have that pressure for every moment to be memorable and that’s also an opportunity for us to mess about with things that we haven’t tried before and sometimes things bleed over. We’re actually working on a TV series now and although we haven’t seen a lot of it yet, we’re coming up with concepts based on the script and the little bits that we have seen. We’ll hand that over to their editors and they’ll place it, tell us what works and what doesn’t and we’ll keep editing and scoring to picture as the process goes on.”

Are you able to us what TV show that’s for yet?

“It’s a historical piece about the late 1800s in the Western United States. It’s not really a Western though; it’s about lots of competing companies and religions all fighting each other and the natives trying to hold back the virus of American expansionism. It’s going to be amazing and hopefully what we’re doing is going to be suitable for it. In the past, we’ve done some weird comedies and that was fun, too. We didn’t make goofy music, but it was a different feel to what we’ve normally done.”

Back to your latest album, titled End. You must have prepared yourself for people assuming this would be the last Explosions in the Sky album?

“Of course. We knew that was going to happen and were worried about that, because we didn’t want to make a declaration that we’re done as a band. We’re always emailing and texting each other ideas for songs and album titles and, for whatever reason, someone came up with End and the absurd boldness of it really struck us. It wasn’t meant to be an apocalyptic statement, it relates to how we, and maybe a lot of people in society, have this pleading of, god, can all of this insanity please just end?

“The last several years have been so crazy – the rug has been pulled from under us and the curtains pulled back on a lot of things. Humanity is always unstable and on the precipice, but it definitely feels heightened now. It’s not just politics; it comes back to the constant barrage of information being blasted at us all the time. At this point, the US feels like a very lost, confused and mentally ill country. People are not getting along.”

Given the subject matter, how does the album reflect that tone sonically?

“There are a couple of dark, harsh-sounding songs on there, but for the most part it’s a pretty optimistic-sounding record. I don’t know if we’re optimistic people – I think of myself as a naively hopeful pessimist. The four of us are probably all that way and that tone seeps into what we do. At the same time, we don’t want the songs to sound monotonous. Like any narrative, there are ups and downs, arcs, dips and valleys, and the goal is to always encompass those emotional dynamics.”

Do you work on tracks in a very traditional way by jamming stuff out in a particular location?

“That used to be the case, but for this record, and to some extent the last one, someone would share an idea, put it up on Dropbox and we’d all listen to it and start discussing and adding our own. Every few months we’ll get together and try to hash out and build stuff that way, so we weren’t really hanging out in a room trying to come up with stuff.

“At the same time, we still wanted End to feel layered and have as much crazy stuff going on as ever and for it to feel live and visceral even though that’s really not how the music was written. Our long-time engineer did a really great job of making it feel very immediate and sounding like a rock record even though none of it was about us actually playing live together in a room.”

In what form do those song ideas tend to take?

“It could be anything – sharing melodies, weird keyboard things or drum parts. We have all of these folders with song ideas and we’ll discuss how they might match together, so there are a lot of ideas going back and forth and because that process is so long and sustained it’s hard to really remember how we actually wrote a song.

Our long-time engineer did a really great job of making it feel very immediate and sounding like a rock record, even though none of it was about us actually playing live together in a room

“The final call has to be unanimous, so nothing gets by that all four of us didn’t sign off on. That can make the process frustrating because trying to get four dudes to agree on everything is not that easy, but it’s very rewarding in the end because we all feel like we have ownership of the songs and our personality is in there. It would probably be easier if one person was calling the shots or leading the charge, but that would be a different band – albeit a more prolific one [laughs].”

Is there a demo stage that you fine-tune in a more professional studio environment?

“We did demos for all of the songs over the course of around 18 months and went to a studio almost a year ago to spend a couple of weeks coming up with more ideas for them. We like to be as prepared as possible because it’s extremely expensive these days to spend two months in a studio, so the songs are fleshed out before we go in with enough room to leave things open for something new to happen.”

What studio did you record at?

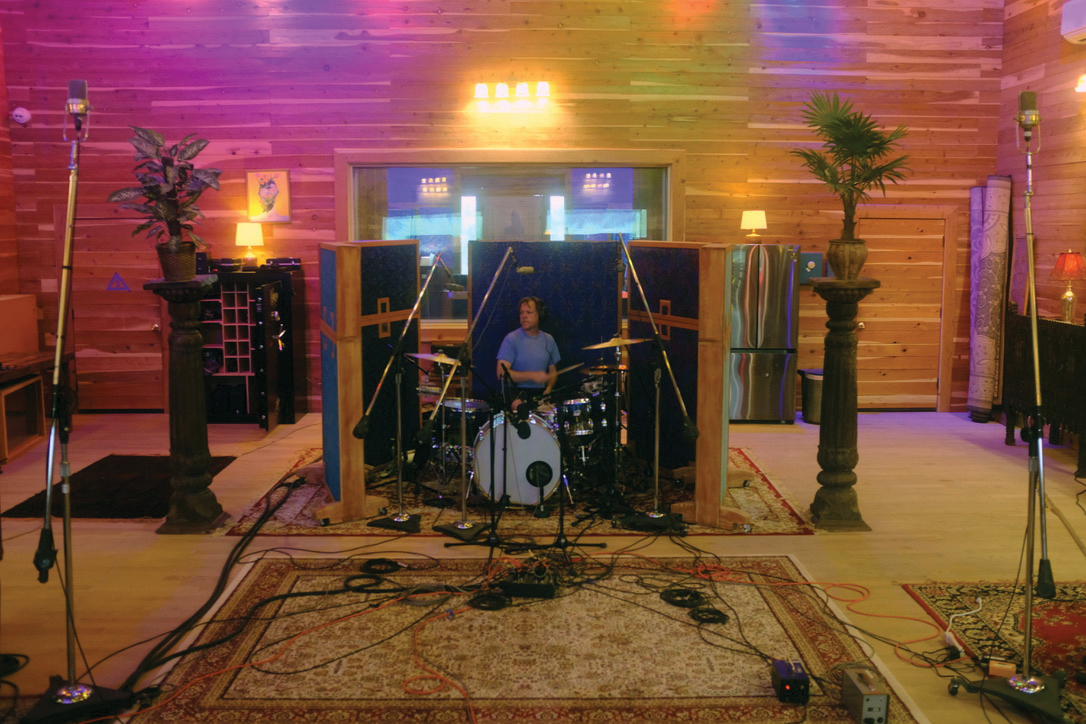

“We recorded the album at a beautiful studio out in the middle of the desert, around 20 miles from El Paso, Texas, and we were pretty much isolated from everything. There were a few different studios on the compound and a house for us to stay at, so I was able to bring my dog for two weeks. To us, that’s ideal. Our engineer John Congleton showed up and there were a couple of assistant engineers there to help us, too.”

John has a vast history in production; you must have been delighted to get him on board?

“We first recorded with John in 2002 and have done every record with him since. We trust him a lot and it’s great to have this other person acting as a soundboard and telling us how he thinks something should be. He’s so good at what he does and always gets what we’re going for, so it’s easy to communicate what we want even if we don’t exactly know how to articulate things.”

You’re the drummer in the band, but it also sounds like everybody is able to get hands on with a variety of instruments if they want?

“I mostly play drums but I’ve definitely created some weird synth parts for songs in the past. We’re all given the freedom to express our views, so I can tell any of the guitar players if a part goes on too long and they’ll do the same if they think I should pull back on the drums or be more aggressive. In those terms, no one feels particularly precious about what they’re doing, it’s all about how do we make this thing that we’re creating better. We constructively criticise and luckily there’s not a lot of ego in the band.”

What kit are you using?

“I’ve been playing the same kit since 2009. It’s made by a father and son team from a company called C&C based out of Kansas City who make these custom drum sets. You can pick the size and finish you want and the drums look beautiful and sound amazing.

“After all these years, I know how my kit feels and what height to put everything at so it feels like an extension of me. I see no reason to get another one until this one blows up or gets stolen. Sometimes I’ll use electronic pads – not for percussion, but a sound effect that we might need to trigger in a live situation.”

As a group, how did you approach recording various takes at the studio?

“Most of the time, everybody tends to work on their individual parts and we decide between us who goes first on which song. Everything was miked up and we created isolation chambers for the amps and built a little drum area. When I’m recording a drum part, I’ll have the demo playing in my headphones and just play along to that while most of the synth stuff goes straight into the desk.”

On the topic of synths, that aspect of your music seems to be quite well-disguised. Is that deliberate?

“There’s definitely some synth on this record and a lot of piano, which we’ve used sporadically in the past. Most of that was done by our guitarist Michael [James]. Synth-wise, it’s often about us just having fun, playing around and looking to add a rhythmic enhancement or drone. We like to layer songs as much as possible and then pull things back where necessary. As you mentioned, the synth stuff never really takes the lead – it’s more like a garnish.”

Do you each have your own synth gear?

“We have bits and pieces at home, but none of us have big synth collections or anything. For the demos, we’ll create a basic idea and use MIDI to run it through Ableton or Pro Tools plugins. At that stage we’re basically creating an approximation of what we’re looking for so when we go to the studio we can hopefully flesh it out with better gear or have a look around to see what they have in storage and start messing around.

“For this record, the studio had a Roland Juno synth that appears in some capacity on every song, and there was a Moog that we used but my memory of it is quite foggy.”

As mentioned, your use of keys is typically textural, but the piano is quite prominent on tracks like Loved Ones and The Fight, which is an exception to the rule…

“I don’t really know why we took that route or remember how it ended up being that way. The track may have started with that piano melody, so it’s possible that Michael simply sent us that piano line and we built the track up from there. Again, the whole process is so scattered that how we made things tends to fade in our memories.”

Are you also using pedals to achieve some of the textural effects you’re looking for?

“Pedals definitely play a big role, but to be honest people always imagine that our pedal boards are three times the actual size. We’ve all got pedals, but we don’t have a crazy arsenal of them.

“We’ve each got a reverb, distortion or sample pedal and a couple of toys or expression pedals that we bring to the studio with us, but like everything else we’ll talk to the engineer and he’ll persuade us to try out other things. It’s the same with amps, we brought all of ours along but don’t remember actually using any of them.”

Are you all equally involved in the mixing and mastering process?

“For this record, we finished recording then John went back home to LA and told us to take a week or two off, step away and just forget about things for a while. That was hard because by the time we got home we really wanted to listen to everything. At some point, John started recording the mix downs and would send those to us daily for us to chime in on what we thought would or would not work. That’s John’s preferred way to do things and I think it’s ultimately the best way to go about the mix stage as opposed to five guys sitting in a room together and nit-picking over every detail.

On our early records, we didn’t have any money so we had to record and mix everything in one day

“On our early records, we didn’t have any money so we had to record and mix everything in one day. That meant we didn’t get the chance to get out of that studio mind-set and come back to the songs with fresh ears. For mastering, we just make some notes for the mastering engineer but tend not to sit with them – they’ll just send a pass for us to make notes or approvals.”

Having a traditional band ethos, we assume that you’re fairly comfortable translating everything to the live stage?

“The last couple of records have definitely been more layered so there are things that we have to trigger. Not the guitar parts, but some of the more textural supplemental stuff will be triggered depending on the song. We have a Mac with Ableton on stage, but for the most part it’s pretty live and none of the guitar parts, piano lines, drums or bass need to be tracked.

“I don’t have a problem with bands who track stuff, but it’s not what we want to do. Because of the process of recording, some of us are playing multiple parts, so we have a guy called Jay Demko who comes with us on the road to play bass or keyboard parts when one of us has to switch instruments.”

Upon completion of the album we understand you got a nice message from Simon Raymonde of Cocteau Twins. It must be nice to receive compliments from such a guitar legend?

“We sent him the record and a couple of days later he sent us a really nice long email going song by song. He’s become a good friend and a mentor in some ways. It’s very weird when you tell people that one of your friends was in Cocteau Twins. In our mind, they’re still this legendary and hugely influential band, so it’s nice to have someone like that who’s been in the industry for so long running the Bella Union label.

“Simon has a pretty spectacular taste in things – so that’s definitely a feather in the cap. For people who like to make interesting, shoegaze-style atmospheres and beautiful guitar stuff, Cocteau Twins are one of the touchstones for sure, alongside Robert Smith of The Cure. They’re bands who used the guitar in very evocative ways but still wrote memorable songs.”

Explosions in the Sky's End is out now on Temporary Residence.