Michigan authorities have long promised to hold key officials criminally responsible for lead contamination and health problems arising from a disastrous water switch in Flint in 2014.

There's not much to show more than eight years later.

The latest: an extraordinary rebuke Tuesday from the state Supreme Court, which unanimously dismissed indictments against former Gov. Rick Snyder and eight others.

The attorney general's office is promising to press on, though hurdles remain even if fresh charges are pursued, including the age of any alleged crimes and a dispute over documents that could take years to resolve.

Solicitor General Fadwa Hammoud, who has led the investigation since 2019, said she's “committed to seeing this process through.”

A look at where things stand:

WHAT HAPPENED AT THE SUPREME COURT?

The court ruled 6-0 that a judge hearing evidence in secret while sitting as a one-person grand jury had no authority to issue indictments, derisively likening it to closed-door justice in the Middle Ages.

The method is so unusual in Michigan that the court said it apparently had never been challenged. Prosecutors typically file charges, then lock horns with defense lawyers in front a judge who decides whether there's enough evidence to go to trial.

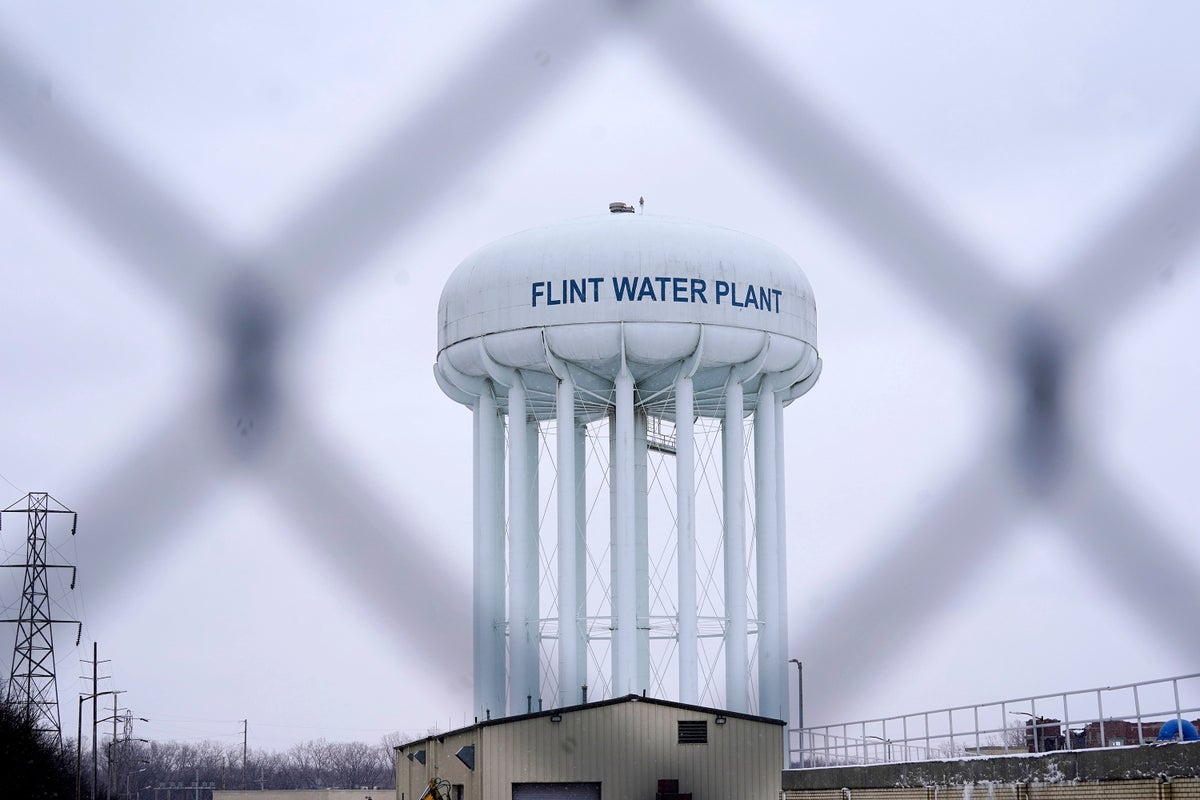

Snyder, a Republican, faced indictment for willful neglect of duty. Flint managers appointed by him tapped the Flint River for water in 2014 while a new pipeline to Lake Huron was under construction. Lead from the city's aging pipes infected the system for more than a year because the corrosive water wasn't properly treated.

Snyder's health department director, Nick Lyon, and Michigan’s former chief medical executive, Dr. Eden Wells, were charged with involuntary manslaughter for nine deaths related to Legionnaires’ disease. Experts say Flint’s water might have lacked enough chlorine to combat bacteria.

CAN NEW CHARGES BE FILED?

Yes, in a more traditional way, but defense lawyers will aggressively challenge them again.

There is a six-year deadline to file misdemeanors, such as the two counts against Snyder and two against former Flint public works chief Howard Croft. Nearly seven years have passed since Snyder acknowledged in 2015 that Flint had a dangerous lead problem and switched the city back to a regional water system.

“That's going to be a problem for a number of these prosecutions,” said attorney John Bursch, a member of Lyon's legal team.

Lyon and Wells were accused of failing to alert the public in a timely manner about the Legionnaires' outbreak. They deny wrongdoing. The deaths appear to fall within the 10-year limit to file felonies.

“It is a great injustice to allow politicians — acting in their own interests — to sacrifice government servants who are performing their roles in good faith under difficult circumstances,” Lyon said Tuesday, referring to Attorney General Dana Nessel, a Democrat.

ARE THERE OTHER STICKY ISSUES?:

Millions of documents — and millions of dollars.

When Nessel's staff took over the Flint water investigation, they seized Snyder-era records from state government that apparently included confidential documents and papers protected by attorney-client privilege.

Defense lawyers cried foul, insisting the records should have been screened by an independent team. They've won so far in two courts, though prosecutors claim it could cost more than $30 million and take years to look at the documents, depending on the number.

The cost and time are irrelevant, Lyon's lawyers said in opposition to an appeal pending at the state Supreme Court.

“No amount of time or money allows the prosecution to keep and use privileged materials against a criminal defendant,” attorney Ronald DeWaard wrote.

HAS ANYONE BEEN CONVICTED?

The criminal investigation of the Flint water crisis began in 2016 under then-Attorney General Bill Schuette and special prosecutor Todd Flood. No one has been sentenced to jail.

Seven people pleaded no contest to misdemeanors that were eventually scrubbed from their records. They included Liane Shekter Smith, who was head of the state’s drinking water division, and Stephen Busch, another key water expert.

Flood insisted he was winning cooperation from key witnesses and moving toward bigger names, but he was canned after Nessel took office in 2019.

Shekter Smith was the only state employee to be fired because of what happened in Flint. But an arbitrator said she was wrongly dismissed in the rush to find a “public scapegoat,” and the state agreed to pay her $300,000.

Busch was paid $522,000 while on leave before returning to work last November, according to records.

Charles Williams II, a Detroit pastor and civil rights activist, said accountability is overdue in Flint.

Families in the majority-Black city, he added, deserve “truth and justice."