The story so far: Dengue is the world’s fastest-growing vector borne disease: evidence shows over the past 50 years, there was a 30-50-fold increase in dengue cases in tropical and subtropical countries, like India. While dengue is largely accepted as an annual epidemic in several countries (impacting more than 3.6 billion people) recurring every monsoon, the face and anatomy of the disease are changing.

A new study led by researchers at the Indian Institute of Science found the dengue virus has evolved “dramatically” over the last five decades in India. A Lancet study this year drew a similar conclusion, adding that urbanisation, population growth, rising temperatures, and climate change created “conditions for the dengue vectors and viruses to multiply”. In April, Argentina saw its worst dengue outbreak in 25 years.

There is no specific medicine or cure for dengue, making vaccines crucial in preventing infection and disease progression. However, developing a universal vaccine has remained a challenge.

The science of dengue vaccines

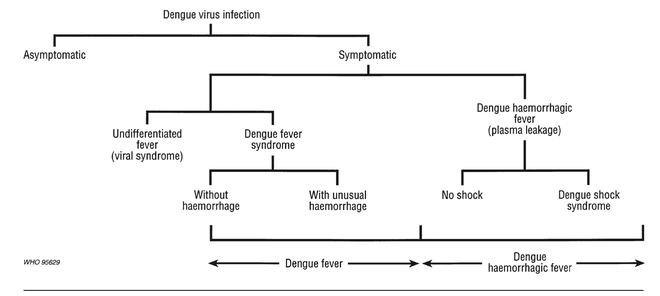

Dengue is transmitted to humans by the Aedes mosquito species, A e. aegypti or Ae. albopictus, which also spreads Chikungunya and Zika virus. There are four serotypes (or types) of the dengue virus — DEN-1, DEN-2, DEN-3 and DEN-4 — each virus interacting differently with antibodies in the human body. Each serotype is capable of manifesting into dengue fever, dengue hemorrhagic fever and dengue shock syndrome.

Five types of dengue vaccines are currently being investigated: live attenuated vaccine (which uses the weakened or “attenuated” form of the virus, such as the measles or chickenpox vaccine); inactivated vaccine (using the dead virus, used for Hepatitis A and rabies), recombinant subunit vaccine (as in COVISHIELD, where non-structural proteins of the dengue virus are used, aiding a balanced immune response), viral vectored vaccine (such as the vaccine against Ebola) and DNA vaccine (for HIV, malaria, TB).

Progress of vaccine trials

The first documented (albeit unsuccessful) clinical trial dates back to 1929, when scientists used virus inactivated using phenol or bile; then during World War II, scientists used weakened strains of DEN-1 and passed it through mouse brain.

Sanofi Pasteur’s Dengvaxia, a live attenuated vaccine, was the first vaccine to receive a nod in 2015, and has been licensed in 20 countries (not in India) since. Other key players include Takeda’s Qdenga (TAK-003), which was recently approved in Brazil and Indonesia, and by the U.S. Food and Drugs Administration (FDA) for priority clearance in November 2022. Another live-attenuated vaccine (TV003/TV005) was developed by the U.S. National Institutes of Health. The TV003/TV005 was licensed to three well-established manufacturers in India (and in China, Japan and Europe) and is under clinical trials.

A host of other vaccine candidates are in varying pre-clinical and clinical trial stages. The Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) in November last year sought approval for clinical trials of a vaccine in works with drugmakers Serum Institute of India and Panacea Biotec. Per a recent Hindu report, Panacea’s vaccine is conducting Phase-III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in 10,335 healthy adults (aged 18-80 years) in 20 sites (ICMR-funded), and the trials were approved by the Drugs Controller General of India in January this year. Serum Institute of India’s vaccine has initiated one-two studies in the paediatric population.

Also under evaluation are 19 DNA dengue vaccines, which are yet to reach final clinical trials, as of 2021.

The picture of an ideal vaccine is thus: it should be safe, provides complete long-lasting protection against all four serotypes (so as to avoid illness after recurring infection), affordable and accessible at an initial stage, and is able to weaken the virus whilst making the body immune (immunogenicity) to subsequent infections.

Why is there no vaccine yet?

Experts ascribe the lag to a dearth of research around different dengue types; the evolving ‘inimitable’ nature of the virus, making vaccine development a dynamic challenge; apprehensions over vaccine safety; lack of funding for a disease that predominantly impacts poorer populations.

A person can be infected with DEN-1, recover with antibodies, but get reinfected with DEN-3 later. The four serotypes effectively require research for four different vaccines — because one may be protected against one serotype for life, but not against the other types. It is difficult to develop a vaccine that effectively targets all four serotypes, experts say. Takeda’s vaccine claims to protect against all four types, but there’s a need to monitor long-term data, experts say.

Another challenge pertains to testing: the lack of a cheap, accessible and sensitive animal model which mimics immune responses in humans after an infection. Mice, for instance, are resistant to dengue infection in itself. The consensus among experts is laboratory animals, used for testing dengue vaccine efficacy, do not reflect the disease’s progression in humans accurately.

The India story

The virus is evolving too, and how the human body responds to it is becoming complex. Dr. Neelika Malavige, a Sri Lanka-based researcher and doctor who has studied dengue’s spread, notes many countries are experiencing a shift in the population pyramids; earlier dengue cases were more prevalent among children, now cases are rising among young adults. As the Indian Institute of Science study also found, DEN-1 and DEN-3 were the dominant strains in India until 2012, post which DEN-2 accounted for the majority of cases. In recent years, cases of DEN-4, which was once considered the least infectious, is now commonly being reported in parts of South India.

The researchers looked at genetic data of serotypes between 1956 and 2018 to find a deviation: the genetic sequence strayed from ancestral patterns and did not match global patterns. This could be due to Antibody-Dependent Enhancement (ADE), when someone infected with one serotype develops a second infection with a different serotype, leading to more severe symptoms. ADE may not only enhance the severity of the infection, the research found, but also change the characteristics of the virus itself. Vaccines work by triggering the immune system, which produces antibodies to fight the infection. Dengue antibodies do the opposite — the virus uses the antibodies itself, giving a boost to the virus, making a second infection more dangerous.

Studying populations with previous infections presents a region-specific research gap that will have a bearing on how effective a vaccine is for a particular target group. Rahul Roy, one of the authors of the study, said that while evaluating the diversity of Indian variants, “we found that they are very different from the original strains used to develop the vaccines”. In other words, research for current vaccines may not account for the virus’s characteristics in countries in which dengue is most endemic. “Such insights are possible only from studying the disease in countries like India with genomic surveillance because the infection rates here have been historically high and a huge population carries antibodies from a previous infection,” said Mr. Roy.

Also read | Climate change increasing risk of new emerging viruses, infectious diseases in India

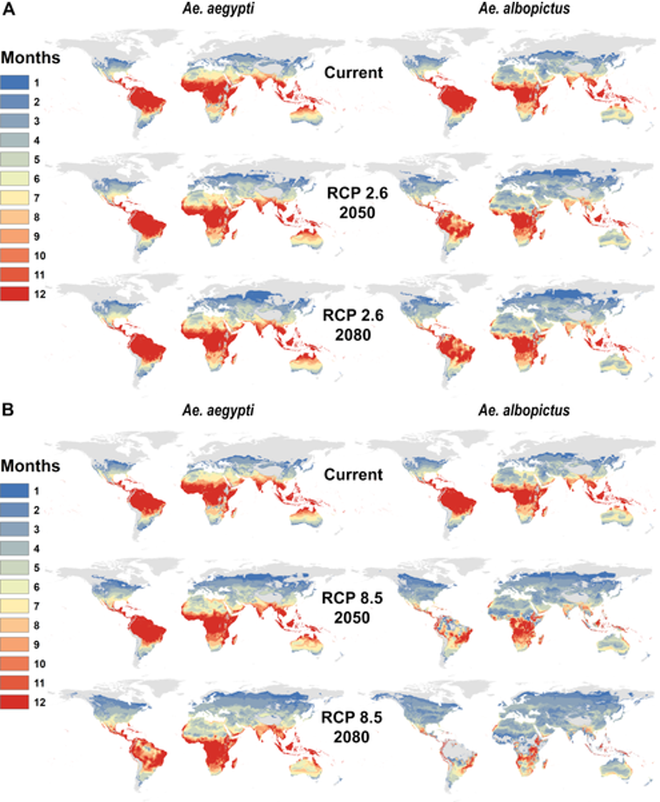

The disease is becoming dangerous, not only due to human vulnerability but also climate change and urbanisation. Climatic factors — including temperature, humidity and rainfall — impact the life cycle and transmission of vector-borne viruses (such as dengue and malaria), such that they are able to grow faster, survive for longer periods of time in the host population and spread to geographies without histories of reported infection. Transmission months of the virus have increased too, research shows, due to shifting monsoon and urbanisation. The number of months suitable for dengue transmission by Aedes aegypti mosquitoes has risen to 5.6 months each year, per a 2022 Lancet report

Prior to 2010, Bihar recorded almost zero cases of dengue, excluding any major outbreaks. The caseload reached 6,712 infections in 2019. “The spread of dengue fever in rural and semi-urban areas is a matter of concern for public health and it can be correlated with unusual climatic patterns arising on account of global warming,” a 2019 study showed. A more recent study projected “expansion of Aedes aegypti in the hot arid regions of the Thar Desert and Aedes albopictus in cold upper Himalayas as a result of future climatic changes”.

Previously reported adverse events to the vaccine may have cast a pall on future development, some say. Take Dengvaxia, the world’s first licensed dengue, which WHO recommended for children aged 9 to 16 years. Almost 14 children in Phillippines who received the vaccine died, and several others were hospitalised. It was found that the immune responses to some dengue virus serotypes waned with time, especially in those who were not infected with any dengue virus previously. In its assessment, WHO noted the vaccine “may be ineffective or may theoretically even increase the future risk of [being] hospitalised or severe dengue illness”. Dengvaxia’s efficacy is limited to those with confirmed previous infections (people living in endemic areas), but its use has declined because it’s difficult to test individuals if they have had dengue in the past, says Dr. Malavige.

Research is thus needed to understand how the genetics of different types of dengue differ, their distribution and how the virus evolves.

Dengue is hugely prevalent. Why is there not enough funding for R&D?

Dengue is a neglected tropical disease, one of 20 recognised by the World Health Organisation. These diseases are historically concentrated among low-income countries, become a “proxy for poverty and disadvantage”, as WHO notes, and thus are ‘non-profitable markets’. Joelle Tanguy, Director of External Affairs at the Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative (DNDi), in a blog post, noted, “There is a pressing need to prioritise R&D for climate-sensitive diseases for which drugs and diagnostics are not developed or are not available, as the medical and pharmaceutical industry focuses on more profitable markets.”

Dengue is also encased in a knowledge gap. There is very little public education, say, about how dengue infection affects pregnant women or may influence outcomes during childbirth, or how dengue worsens with climate change. It is relegated as a non-urgent, recurring endemic that doesn’t demand as much energy or investment as a global pandemic should.

“The fact is that very little funding is available for dengue and to answer these very important questions.”Dr. Neelika Malavige

The funding is linked to lack of awareness, and a sense of misinformed complacency. Radha Pradhan, who works as a nurse trainer with Antara Foundation in Madhya Pradesh and comes across such cases, mentions a significant knowledge gap among local healthcare workers as well. For people working in areas where dengue cases have historically been low but are now rising, it becomes a concern because “those who haven’t experienced cases, they won’t be able to tell the basic symptoms and differences about dengue diagnosis.”

The unfavourable history of safety risks may also present a challenge to how the vaccine is accepted, more so by vulnerable groups such as children and pregnant women. For vaccine acceptance of any kind, however, awareness and knowledge of dengue’s anatomy is critical, experts say.

What does dengue treatment look like right now?

There is no prescribed treatment plan for the dengue virus. The focus remains on treating symptoms, such as fever and fatigue, and platelet transfusion for those in whom the count drops drastically. Health practitioners argue for better diagnostic facilities and public health infrastructure, for early detection and timely intervention.

An editorial in the International Journal of Infection Diseases acknowledges that the development and testing of dengue vaccines, along with a concerted national effort to establish surveillance systems and effective vector control, could bring about a “paradigm shift in global dengue control”.