The story so far: In 2020, a study on Maharashtra’s cane cutters identified a widening blind spot in women’s health: the unchecked rise of hysterectomies. Laws regulating private clinics were poorly implemented, awareness about the procedure of uterus removal was dismal, gynaecological services were absent and no standard protocols existed, the authors noted.

The problems remain the same three years later. Half of the women reportedly go through hysterectomies before they turn 35, per National Family Health Survey-5 data. The Union Health Ministry recently urged State Governments to audit hysterectomy trends in public and private hospitals, in response to a Supreme Court petition arguing that women from marginalised locations are at risk of unjustified hysterectomies for economic gains and exploitation. The top Court last month also gave a three-month deadline to States and Union Territories, directing them to implement these Health Ministry guidelines. “There has been a serious violation of the fundamental rights of the women who underwent unnecessary hysterectomies,” the judgment said.

Somya Gupta, a Delhi-based gynaecologist, says the intervention is a “welcome step”, adding that a hysterectomy “should be a last resort when you can’t treat something with medicine”.

What are the criteria for getting a hysterectomy?

After caesarean deliveries, hysterectomies are the second-most frequent procedure in women of the reproductive age group. Medically, hysterectomies should be conducted in the later part of an individual’s reproductive life, or as an intervention during emergencies. Noted medical indications for removing a uterus include fibroids (growths around the uterus), abnormal uterine bleeding and uterine prolapse, chronic pelvic pain, and premalignant and malignant tumours of the uterus and cervix. In some cases, oophorectomy, the removal of ovaries (the primary source of estrogen), is also frequently performed, which is a form of surgical menopause and linked to several chronic conditions.

Reports suggest that in many cases, hysterectomies are presented to women as a “permanent solution” for health issues, even when other low-invasive treatments could work.

The highest percentage of hysterectomies (51.8%) were to treat excessive menstrual bleeding or pain; 24.94% for fibroids; 24.94% for cysts; 11.08% for uterine disorder or rupture, according to NFHS-5 data. Yet, studies have shown that “many of these causes were considered to be treatable and surgery could be avoided”.

Health risks

Health practitioners have witnessed worrying trends over the years with respect to age, location, social-economic background and intention.

The average age at which hysterectomies are conducted among Indian women is 34, per community-based studies. This is a deviation from the global trend: in high-income countries, the procedure is typically for women aged above 45. Most surgeries happen in private hospitals (33,559 procedures) as opposed to government hospitals (11, 875), the Union Government said in March this year. A majority of these cases are reported among socially and economically disadvantaged women (the Supreme Court petition argued most women belonged to Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, or Other Backward Communities). And the procedure can be easily misused — either in the hands of private clinics who earn profits (from insurance money) or by contractors in unorganised sectors such as the sugar-cane-cutting industry, where ‘wombless women’ are the norm to eliminate the need for menstrual care and hygiene among workers.

What measures has the government taken so far?

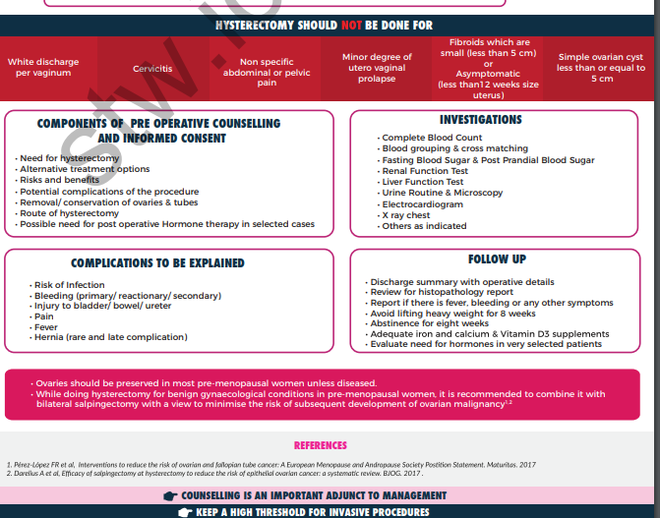

The Union Health Ministry in 2022 issued guidelines to prevent unnecessary hysterectomies — listing possible indications of when hysterectomy may be required and alternative clinical treatments for gynaecological issues. Further, they recommended setting up district, State-level and national hysterectomy monitoring committees which to collect data on age, mortality, and occupations, among other details. States and Union Territories are expected to conduct audits of hysterectomy trends and furnish a report, as per the Supreme Court order.

The government also proposed a grievance portal, monitored by the National Hysterectomy Monitoring Committee, for hysterectomy beneficiaries.

In particular, the guidelines emphasise that authorities should report hysterectomies conducted for women less than 40 years of age and incorporate the reason for hysterectomy into the existing screening checklist. “All States and Union Territories shall adopt the Guidelines within three months and report compliance to MoHFW,” the Supreme Court said.

The monitoring committees are also tasked with creating awareness, among both practitioners and patients, about bodily anatomy, the role of uterus and when hysterectomies are actually indicated. A 2017 study from Gujarat found most women assumed that the uterus served no role outside of pregnancy and that removing the uterus would solve their health issues. There is a dearth of awareness, experts say, and in the absence of sexual and reproductive health education, “informed consent” can never be taken.

“The number one problem [with hysterectomies] is that the patient is ignorant about their own physiology and anatomy, and they need to be educated,” says Dr. Gupta, adding that in many cases women may relate migraines, gastric reflux, weakness or muscle cramps with the vagina or uterus. The most common misconception is that of vaginal discharge, which happens due to estrogen and is perfectly normal. But in many cases where women experience white discharge and may have lower back aches, “they think it is their bone which is melting and coming out through the uterus”.

A 2019 investigation also found that women from rural areas look at hysterectomies as a way of increasing days of productive work and earning more wages. “People have turned healthcare into a business”, and “on the other side of the table is somebody who is just out to make quick money and do quick surgery,” Dr. Gupta says.

The government’s flagship health insurance programme Ayushman Bharat Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana provides health cover of ₹5 lakhs for 1,949 procedures— including hysterectomies. The government has authorised 45,434 hospitals to conduct these operations and also developed two standard treatment guidelines for hysterectomy-related procedures. These guidelines, developed by the Union Health Ministry and the Indian Council for Medical Research (ICMR) in consultation with health experts, explicitly state that the procedure should be “considered only when childbearing is completed and rarely in younger patients”.

Under the Clinical Establishments (Registration and Regulation) Act, 2010, hospitals and healthcare facilities found to have coerced women into hysterectomies without informed consent can be blacklisted. The Centre told the Supreme Court that several hospitals were blacklisted and FIRs were filed against facilities that violated norms. Some were also de-empanelled from the government health insurance programme Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana after investigations found that private practitioners coerced women, to rake in insurance profits from the State.

11 States, including Arunachal Pradesh, Sikkim, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Bihar, Jharkhand and Karnataka, have adopted the Act. Maharashtra has not. In response to the petition, Bihar said that it has also directed hospitals to obtain permission from the concerned insurance provider before conducting hysterectomies for those aged forty or below.

The petition noted that unnecessary hysterectomies violate international conventions to which India is a signatory. These include the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (which recognises people’s right to control their health and body, including reproductive and sexual freedom), the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

Is there an implementation gap?

The Supreme Court and Centre’s reiteration of guidelines came in response to a petition by Dr. Narendra Gupta, a public health expert. He argued that despite the provisions, private hospitals in Bihar, Chhattisgarh and Rajasthan engaged in unethical practices and unnecessary procedures, did not inform women of side effects or take their informed content. . In doing so, they “failed in providing and regulating constitutionally mandated reproductive healthcare to women” and violated their “rights to health, bodily integrity and informed consent,” the petition said.

It added that patients visited private hospitals, which increased in visibility despite being located at a distance, due to gaps in the National Rural Health Mission, a 2005 scheme to provide healthcare to poor women, children and rural populations. The same hospitals recorded an “unnatural” hike in the number of hysterectomies performed under the RSBY scheme. An Andhra Pradesh study found nearly 60% of hysterectomies were conducted on women aged under 30, with 95% odone in private hospitals; there was no information on follow-up procedures or case details in the discharge summaries.

In 2019, the Maharashtra Government commissioned a study of women cane cutters’ concerns in eight districts of Marathwada. The recommendations — including passing the Maharashtra Clinical Establishment Act and conducting regular clinical audits of private hospitals — were not implemented even as of 2023, as per reports.

Lack of awareness of gynaecological issues

The gap thrives in a culture where gynaecological care and disorders — outside of pregnancy — exist in oblivion, experts say.

Some reports show “rasoli” — indicating a tumour or growth— is often cited as a reason for hysterectomies in medical documents. These may be benign growths, manageable by conducting investigative tests and undertaking alternative treatments. This rarely happens, the petition noted, as women are made to believe the surgery is an emergency.

Moreover, medical ailments are not adequately investigated due to lack of resources, unawareness about gynaecological diseases and misinformation. Dr. Gupta explains that non-invasive interventions, such as laparoscopy, become unfeasible because they are expensive, unavailable in public hospitals and require expertise.

While India has a Draft National Policy for Women which recognises gaps in healthcare for menopausal women, there is little focus on women in their procreating ages or when they cross 45.

NFHS data on hysterectomies

What about long-term treatment of women?

Hysterectomies may cause long-term injuries and disabilities, requiring follow-up and post-operative care, both rarely available or affordable. In some cases, when hysterectomies are unindicated, women may continue to suffer post-surgery and need additional surgery. “If they had pelvic pain due to endometriosis, it might not be solved by hysterectomy alone.,” Dr. Gupta says.

In other cases, patients may need medical support such as hormone replacement therapies (if both ovaries and uterus are removed and there are menopausal symptoms). But these interventions are limited to private hospitals and remain unaffordable for low-income groups.

There is some global evidence to show that women who underwent hysterectomy with oophorectomy — before the age 50, sans hormone therapy — had 1.8 higher odds of all-cause mortality. A 2023 paper concluded that the high prevalence of hysterectomy in parts of India “could lead to similar patterns”, and long-term impact needs to be closely monitored.

What is needed instead?

“Hysterectomy has a role to play,” Dr. Gupta says, in cases where someone has big fibroids, or early symptoms of cancer. “It can be a lifesaving surgery and may cause more benefit to the patient instead of harm.”

In 2019, a national consultation panel identified three challenges: the need for clinical and population-level guidelines; information on gynaecological morbidity at the primary level and required treatment services; and monitoring and regulating hysterectomies, particularly among younger women and people with “benign” conditions.

In the present case, Chief Justice D.Y. Chandrachud also suggested that hysterectomies for those under 40 should be conducted on approval by two certified doctors. Yet, health experts warn these measures may curb access instead: women in need of treatment may be turned away due to gaps in government-run healthcare.

Some trends

Some advocate for regulating the private sector. to rein in exploitative practices. Oxfam India, in a 2013 report, cautioned against continuing a public-private partnership in healthcare (allowing procedures in private hospitals using government insurance) until the sector can be regulated. A report by NGOs suggested that “government hospitals should provide treatment to avoid unindicated hysterectomies, and if not treatable, hysterectomies should be done in government hospitals.”

But others argue that pinning the blame on physician malpractice is akin to mistaking the forest for the trees, and more investment in public health infrastructure is needed. “The gap left by the public health system combined with a government policy of proactively promoting the private sector has led to the proliferation of private health providers which are unregulated, unaccountable, and out of control,” Oxfam noted.

Efforts are also required to improve menstrual and sanitation facilities, particularly in rural areas, and to create awareness among both patients and clinicians, including knowledge of alternative treatments. The Federation of Obstetric and Gynaecological Societies of India launched a ‘Save the Uterus’ campaign in 2019 to advocate and train doctors for non-invasive procedures to treat uterine and other issues rather than simply removing the uterus.

Dr. Gupta notes the trend of “mass hysterectomies” is inextricably linked to misconceptions about menstruation, ovulation, pregnancy, childbirth and breastfeeding. It requires a larger cultural shift where people need to look at, and learn to care for, wombs and women even outside their reproductive value in a patriarchal society. “We need to spread awareness about issues of women that are not related to pregnancy and childbirth — that area of women’s health is totally neglected,” she says.