NEW DELHI: Cash-strapped Pakistan economy is in dire states with plunging currency, soaring inflation, a balance of payments crisis, diminishing forex reserves all amid political chaos and a deteriorating security situation.

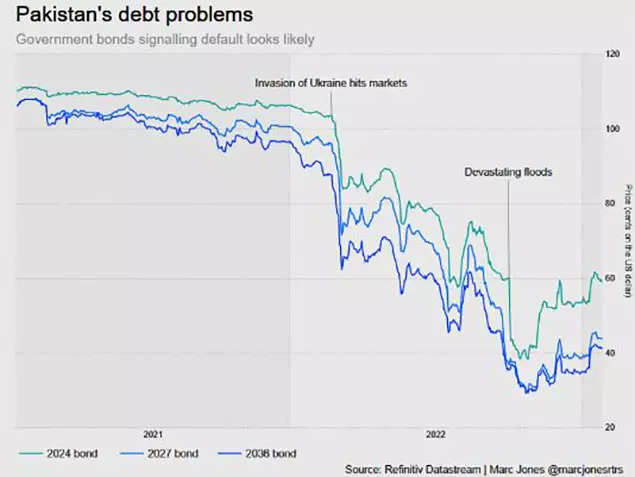

A rapidly devaluing currency and a record fall in Pakistan's foreign exchange reserves have fueled speculations that the country might be heading towards default in repayment of debt.

The deepening economic turmoil is just one aspect. Along with it, Pakistan is also struggling in the aftermath of last summer’s devastating floods that caused up to $40 billion in damages. This made it difficult for the government to comply with some of the IMF’s conditions, including increases in the price of gas and electricity and new taxes.

The country is at present struggling to arrive at a consensus with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for a bailout package.

Talks were held in a bid to unlock funds from a $7 billion bailout designed to ward off economic meltdown. The talks, to continue through February 9, are meant to clear the IMF's 9th review of its Extended Fund Facility, aimed at helping countries with balance-of-payments crises.

The full-blown economic turmoil and its recent and biggest ever currency devaluation raises risk of default, unless the country receives massive financial support.

How severe is the situation

According to a report by The Economist, Pakistan's political, economic and environmental crises are mutually reinforcing. It noted that payments from the bailout programme agreed in 2019 were suspended a year ago after its then prime minister Imran Khan, facing a growing prospect of parliamentary defeat and ejection from office, reintroduced fuel subsidies. However, he was ousted from the position in April last year.

Khan's successor, Shehbaz Sharif’s government vowed to fulfil the IMF’s conditions but backtracked in September when, panicked by the floods, it sacked Miftah Ismail, its finance minister. His successor reversed some of his policies, prompting another suspension of payouts.

Apart from the political turmoil, crisis-hit Pakistan also suffered one of its major power outages on January 23 as part of the Shehbaz Sharif government's energy-saving measure which backfired, leaving citizens in panic and a state of confusion.

This is not the first such instance of a nationwide blackout in Pakistan. The neighbouring country has struggled with power outages for years, including a major incident in January 2021 when a power plant fault collapsed the national grid, prompting calls for an overhaul of aging electricity transmission infrastructure.

The sorry state of Pakistan's power sector is emblematic of an economy that has lurched from one IMF bailout to the next, with electricity outages occurring frequently due a lack funds to upgrade aging infrastructure.

In addition, a follow-up wave of inflation, fuelled by global factors and economic mismanagement, is making their situation harder, the Economist report noted.

Annual inflation reached 27.6% in January, the highest level since 1975. The rupee is crashing and with foreign exchange reserves dwindling, the country faces its worse balance of payments crisis in peacetime, the report added.

While, long queues of automobiles and motorcycles were witnessed at filling stations in Pakistan's capital city of Islamabad and the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province due to reduced supplies by oil marketing companies, Pakistan-based Dawn newspaper reported.

According to petrol dealers, companies cut down supplies of petroleum products to the province over long delays in the issuance of letters of credit by private banks for imports.

What Pakistan seeks from IMF

Pakistan is seeking a crucial installment of $1.1 billion from the fund — part of its $6 billion bailout package — to avoid default. Talks with the IMF on reviving the bailout had stalled in the past months.

“Our economic challenges at the moment are unimaginable," he added. “The IMF conditions which we have to fulfill ... are beyond the imagination. ... But wee we don't have any other option."

The bailout is much needed as the South Asian nation has reserves of just $3.7 billion. This is barely enough for 3 weeks of essential imports, according to a report by Reuters.

It desperately needs the International Monetary Fund to release an overdue tranche of $1.1 billion, leaving $1.4 billion remaining in a stalled bailout programme set to end in June.

The lender had set several conditions for resuming the bailout, including a market-determined exchange rate for the local currency and an easing of fuel subsidies. The central bank recently removed a cap on exchange rates and the government raised fuel prices by 16%.

However, if in case Pakistan does not receive this bailout package, default risk increases.

What would a default mean

Pakistan's central bank took a policy decision to allow opening of import letter of credits in a staggered manner just when its reserves fell below $5 billion in December last year.

The IMF scheduled its 9th review with the country which is still underway in Islamabad. This decision was triggered by the massive devaluation in Pakistan rupee which happened last week.

A report by Dawn analyses what Pakistan's scenario would look like in case in slips into default. It says a default for a country like Pakistan with large exposure in commercial loans means defaulting against commercial debt.

The report notes that while bilateral debt can be rolled over, debt from multi-lateral organisations often has long term maturity cycles, making a country's default vulnerability depend primarily on commercial loans.

With Pakistan's reserves decling to such low levels, chances of default against commercial debt rises. In that case, the central bank would refuse repayment to commercial lenders or service their debt, the report said.

This would in turn impact the government's ability to raise fresh commercial debt and dampen the trust of other international lenders. The report added that will limited debt inflows, dollar would also decline, thereby impacted the country's import-export situation. Hence, the government would have been forced by circumstances to keep current account deficit close to zero, Dawn said.

It further added the Pakistan currency would have lost value drastically since too much rupee would have been chasing too few goods. Since imports would cost more, this would also lead to a rise in inputs cost for the industry, thereby pulling down overall level of production in economy.

In addition, sky-high inflation would have curbed the consumption power of people even more. Besides, high unemployment as a result of increased layoffs would have left some with money but nothing to buy and many without even money to buy, the Dawn report added.

It also noted that with a massive external debt pile of $126 billion and just $3 billion in reserves, Pakistan was definitely headed the Sri Lanka way. However, it did not default and any chance of it doing so have been left behind.

PM warns of a tough time

Last week, Pakistan's prime minister warned of a “tough time" as his government struggles to comply with conditions set by the International Monetary Fund for the next tranche of the country's bailout package.

Prime Minister Shahbaz Sharif spoke just days after IMF officials and Pakistan’s Finance Minister Ishaq Dar resumed talks in the capital, Islamabad, on its bailout — even as the country's foreign reserves dwindle further, and are now at the dangerously low level of $3 billion.

Sharif has repeatedly pledged that his government will not default but will manage to secure the loan from the IMF.

With Pakistan's debt-to-GDP ratio in a danger zone of 70%, and between 40% and 50% of government revenues earmarked for interest payments this year, only default-stricken Sri Lanka, Ghana, and Nigeria are worse off.

"There is just a long-term indebtedness problem," said Jeff Grills, the head of emerging markets debt at Aegon Asset Management, who held Pakistan bonds until the floods hit.

"It is more a question of when they need to restructure, rather than if."

Most of Pakistan's bonds are still trading at less than half their face value.

Sharif is optimistic that the IMF will resume disbursements. "An agreement with the IMF, God willing, will be done," he said at an event last week in Islamabad, the capital. "We will soon be out of difficult times."

(With inputs from agencies)