The story so far: The Rajasthan government recently released the draft Rajasthan Platform Based Gig Workers (Registration and Welfare) Bill, 2023 — the first legislation of its kind in India outlining social security and welfare measures — and invited feedback from stakeholders, including the State’s approximately three lakh gig workers, till July 7.

The demand for a legal framework echoes throughout India’s 77-lakh-strong gig workforce (expected to swell to 2.34 crore by 2030). Gig workers, portrayed by many companies as ‘partners’ partaking in an ‘economic revolution’, often work unregulated hours, inadequate wages, do not have social security, and face discrimination and harassment at the hands of both companies and customers.

Shaik Salauddin, the National General Secretary of the Indian Federation of App-Based Transport Workers (IFAT), says the present Bill is both a “milestone” and “mirror,” reflecting the status of gig workers in India and the worldoperating as they do in a system shaped by algorithms and facing limited economic opportunities. Experts and unions, however, say the Bill needs to be tightened in language and scope, so that it lifts them to a place where no company or algorithm decides who gets work and how they are compensated.

What does the Bill propose?

The Bill applies to “aggregators,” defined as digital intermediaries connecting buyers and sellers, and “primary employers,” an individual or organisations engaging platform-based workers for providing one or more of the following services:

Industries under consideration

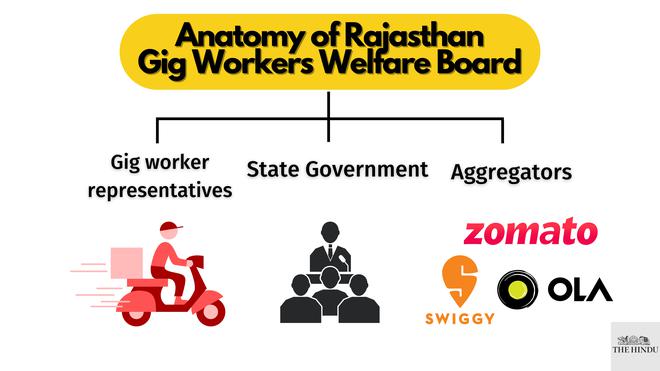

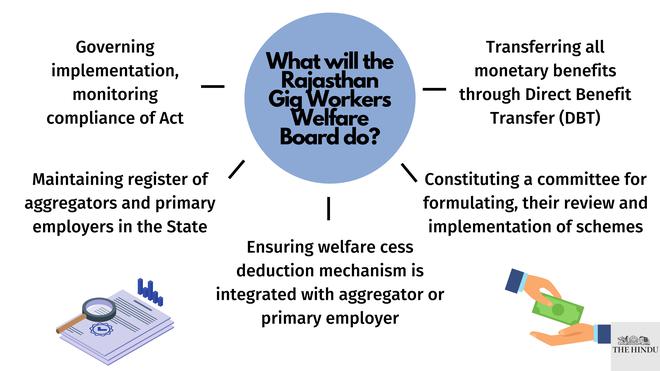

The Bill proposes a Welfare Board — comprising State officials, five representatives each from gig workers and aggregators, and two others (“one from Civil Society and another who evince interest in any other field”). At least one-third of the nominated members should be women. The Board will “set up a welfare fund, register platform-based gig workers, aggregators and primary employers... facilitate guarantee of social security to platform-based gig workers and to provide for matters connected therewith or incidental thereto.” They are the vessel to “govern the norms of implementation and monitoring of the Act,” and will present an annual report to the Rajasthan Government, which will be laid before the State Legislature.

The Board will maintain a database made available on a web portal. Aggregators can register themselves and provide workers’ details, duration of engagement with the platform and if they are employed with other aggregators. Each gig worker will receive a unique ID, and this registration “shall be valid in perpetuity.”

In their recommendations to the government, which The Hindu has reviewed, labour unions have objected to vague terminologies within the Bill that may offer escape hatches to companies. A ‘gig worker’ is currently defined as someone who “earns from such activities outside of the traditional employer-employee relationship and who works on a contract...” They recommend the definition specify someone partaking in a work arrangement “mediated by any technology platform (app-based and web-based) as an intermediary.” This would expand the scope to include workers employed through subcontractors and third-party service providers. Unions also argue for removing the concept of a “primary employer” from the Bill to curb exploitation by unlicensed third-party service providers.

Chiara Furtado, a tech and labour researcher with the Centre for Internet and Society, also notes that the Bill’s definition of ‘gig worker’ draws from the Code on Social Security (COSS), which categorically places the gig worker outside an employer-employee relationship. “It’s unclear [if the government] is bound by the Code,” she says.

Activists also recommend that the domain of the “two representatives from civil society” should be specified, to include one with expertise in labour laws and social policies and the other specialising in technology in a platform-based economy.

Finding the money

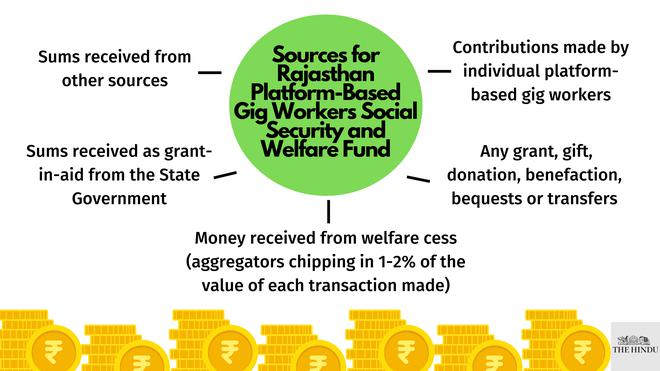

Money will be the divisive point, activists note. Per the Bill, the Board will create and monitor a “Social Security and Welfare Fund” comprising contributions made by individual workers, State government aids, other sources and a ‘welfare cess’ — a cut from each transaction — which the aggregator is required to pay. The rate of the welfare cess will not exceed 2% nor fall short of 1% of the value of “each transaction,” and aggregators are required to submit the amount within the first five days of a month. The Bill provides for setting up a Central Transaction Information and Management System (CTIMS) that maps payments generated on platforms, recording commission charged, GST deducted, payment made to the worker, and welfare cess contributed by companies, among others.

Unions, however, objected to contributing to the fund, arguing that it should be sourced only from aggregator companies and State funds, owing to the fluctuating and inadequate nature of pay. In a survey of app-based transport and delivery workers in Mumbai and Delhi, released in 2021, more than 90% said gig work is their primary source of income; 50% said this money is “barely sufficient” to cover basic expenses and financial obligations of their households. COVID-19 has simultaneously worsened economic realities and pushed many to platform work, which makes legal protections for workers a burning issue, says Ms. Furtado.

Per 2022’s Fairwork India rankings, no platform had a policy to ensure workers earn at least the “local living wage” (the income required to sustain a decent standard of living based on work-related costs, geography and family size.)

Moreover, it is unclear if “each transaction” under the welfare cess is limited to a particular ride or delivery, or if it will include other payments — such as incentive structures and subscription models — offered to workers. “There is a concern the contributions made can then be offloaded and extracted through these other channels,” Ms. Furtado says. Unions also note the cess should look at the total value of a transaction regardless of deductions (commissions, discounts, incentives or offers). A salon worker with Urban Company on average has gross earnings of ₹61,071, but the income in hand comes down to ₹29,164 after cutting commission, product and travel costs.

Does the Bill recognise workers’ rights?

Under existing labour laws, ‘partners’ are not ‘employees’ because theirs is not a “fixed term of employment” — marked by providing exclusive service to one provider for a specified duration. Several critiques, including one made by a U.K. court, have objected to this rationale, arguing that gig workers need protection for they are in a “subordinate and dependent position vis-a-vis their employers,” and exercise no control over their employment contract, remuneration and penalties.

The COSS, passed in 2020 and yet to be implemented, similarly carried “restrictive criteria” about eligibility, but those aspects are done away with in the Rajasthan Bill, Ms. Furtado says. The Bill states any person has the right to be registered the minute they join an app-based platform, regardless of the duration of the work or how many providers they work for.

The Welfare Board is expected to formulate schemes “for social security,” listing only accidental insurance and health insurance, and “other benefits concerning health, accident and education as may be prescribed.” 95.3% of Ola and Uber drivers lacked insurance coverage (accidental, health or medical), per a report. Workers also suffered from occupational health issues, including backache, constipation, liver issues, waist pain and neck pain.

Unions have recommended that benefits available to gig workers be enumerated clearly in the Bill, expanding on the clause “other benefits.” These may include provident funds, life and disability cover, health and maternity benefits, housing, skill upgradations, funeral assistance, old age protection, and protection against wage loss due to internet shutdowns — welfare measures which apply to those employed in the formal economy.

One responsibility of the Welfare Board, unions say, should be to assist workers in negotiating contracts by developing standard formats and principles for aggregators. The All India Centre Council of Trade Union (AICCTU) last year noted “the design of systems and logics of compensation are completely invisible to workers, undermining their capacity to protect their rights.” The unions’ submission demands that any change to the algorithms or incentive model, which would affect workers’ earnings, be notified at least 48 hours in advance.

The Bill currently does not specify what happens to the data of gig workers (their work history, money earned, savings, personal details) once collected by companies. “This is in the context of very high information asymmetry between platforms and the worker that have already existed. Who has access to the data, how much data do they have access to, who audits this data?” asks Ms. Furtado. Labour unions have recommended the Bill be amended to specify that workers have a right to their data.

What about workers’ grievances?

Gig workers “have an opportunity to be heard for any grievances” with “entitlements, payments and benefits provided under the Act.” Per Section 15, a worker can file a petition physically before an officer or online through the web portal. The authorised officer will direct the aggregator/primary employer to pay appropriate compensation if required. The employer can object to the order within 90 days before an ‘Appellate Authority’; such authority may accept the appeal even later “if it is satisfied that the appellant was prevented by sufficient cause from filing the appeal in time.”

Several reports — of workers with Zomato, Urban Company, Ola, Swiggy — have documented ineffective and unresponsive redressal mechanisms. Urban Company workers are currently protesting the “arbitrary” blocking of their accounts and a lack of support. Algorithms “determine penalties and grievance redressal, which have an impact on the occupational health and safety,” AICCTU noted.

Labour unions suggest diversifying the medium of grievance platforms to include mobile apps, 24x7 helplines, information and facilitation centres, and Rajasthan Sampark portals. Moreover, the contours of grievance redressal should be outlined in a protocol, specifying the timeline and role of grievance redressal officers, building a tracking mechanism for workers and solifidying other norms “to uphold the rights of the worker.”

Does the Bill hold aggregators accountable?

An aggregator’s duties under the Bill include: depositing welfare cess on time, routinely updating the database of gig workers, and documenting any variations in numbers within one month of such changes. If they fail to comply, aggregators will be fined up to ₹5 lakh for the first offence and ₹50 lakh for further violations; primary employers will pay up to ₹10,000 for the first offence and ₹2 lakh for subsequent violations. If companies fail to pay fines, officials can use methods prescribed under the Rajasthan Land Revenue Act, 1956, to recover the due amount.