The story so far: India wants to build a pan-India unified database of demographic data of individuals — from the moment of birth to the day they die. The Registration of Birth and Death (RBD) Amendment Bill, 2023 was tabled in the Lok Sabha on July 26. The proposed changes will make birth certificates a necessary document to unlock basic services, such as voting, education, and food welfare schemes. The Centre is also likely to mandate Aadhaar during the registration process.

This real-time, dynamic national-level population database will also be linked with other demographic databases: ration cards and passports, voter rolls and the National Population Register for “efficient and transparent delivery of public services and benefits,” the Bill’s Objects and Reasons stated. This will avoid a “multiplicity of documents to prove date and place of birth in the country”.

The Bill comes at a contentious time, as the methodology and scientific rigour of India’s nationwide surveys are disputed, the data protection Bill faces stiff opposition, and the Census has been delayed indefinitely ahead of the 2024 Lok Sabha elections.

How are births and deaths currently registered?

The mandatory documentation of births and deaths is governed by the RBD Act passed in 1969 and State Rules framed using the Model Rules, 1999. The Act was implemented “to promote uniformity and comparability in the registration of Births and Deaths across the country,” the official website states. Births, stillbirths and deaths are to be registered within 21 days of occurrence; violating the provisions is a punishable offence, incurring a fine of ₹5.

The Act requires States and Union Territories to maintain individual databases on the Civil Registration System (CRS). CRS comes under the operational control of the Registrar General of India (RGI). Between 2010 and 2019, the registration level of birth increased from 82.4% to 92.7%, and registered deaths increased from 66.4% to 92% — the increase was attributed to the growing population, greater awareness and the interconnected pathways of welfare services (a birth certificate may be required to get an Aadhaar card, for instance.)

17 States and UTs use the portal to register births and deaths. Others — including Gujarat, Punjab, New Delhi, and Jammu & Kashmir — either maintain separate portals or update the portal partially. Some States have digitised and integrated their data with individual State Resident Data Hubs (a storehouse of Aadhaar details, demographic data and photographs.)

The Ministry of Home Affairs shared a draft of the RBD Bill in October 2021, and it was to be tabled for discussion in the winter session of the parliament last year, but was delayed due to paucity of time, officials told The Hindu earlier.

A centralised database

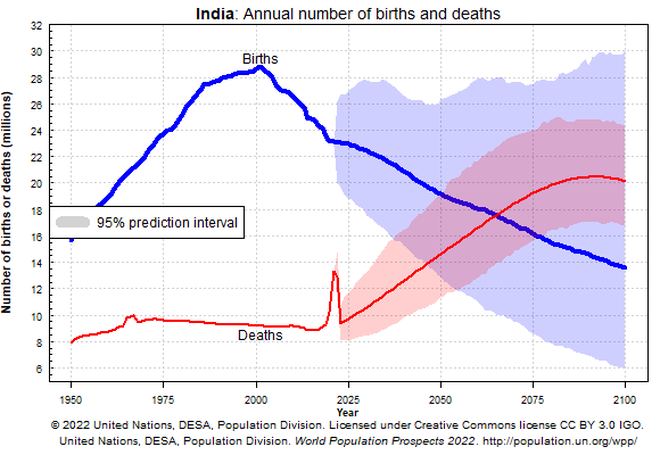

“It’s an irony that despite being one of the most populated countries, we do not get population data in real-time and have to depend on sample surveys to prepare public-welfare policies,” a senior official told a media outlet in 2021. The proposed amendments will bring individual databases onto a common platform, a repository that the RGI (which operates under MHA) will maintain.

State-specific data is currently sent as annual statistical reports to the RGI. The Bill, however, compulsorily requires States to share granular, real-time data, by giving the RGI access to the Application Programming Interface. The central data reservoir will be updated in real-time, without any human interface and independent of location. For instance, an individual will be automatically added to the electoral roll when they turn 18, and removed after their death.

Experts have highlighted how this may approximate to 360-degree surveillance— a panopticon of sorts— where the MHA can track people in real-time and predict what welfare support they require.

This database can be used to update other portals, including the National Population Register (the first block for building a pan-India National Register of Citizens), electoral register, Aadhaar, ration card, passport, driving Llcense databases and “such other databases at the National level as may be notified” through the insertion of a Section 3A in the Act.

MHA’s annual report in 2021 pointed to the need of updating NPR again, first collated in 2010 and updated in 2015 with Aadhaar, mobile and ration card numbers, in order “to incorporate the changes due to birth, death and migration.” NPR figures will also be revised post the Census, and if new amendments are passed, MHA may access data for census enumeration via NPR. The Census Act of 1948 bars sharing any individual’s data with the State or Centre, a restriction that the NPR can bypass.

Pertinently, the draft Bill will make birth certificates a mainstay of daily life — a ‘passport’ which assigns individuals a unified marker governing their mobility, allowing access to basic services such as voting, admission into schools and colleges, and registration of marriage.

Will Aadhaar play a role?

Aadhaar, the world’s largest identity biometric database, could be mandated for birth and death registrations, The Hindu reported. If approved, the Bill will amend Section 8 to read: those responsible for information would also be required to provide “Aadhaar number, if available, of parents and the informant in case of birth, and of the deceased, parents, husband or wife and the informant in case of death.”

K. Narayan Unni, a former Deputy Registrar General, previously called this an “unnecessary amendment” and a formality. States are already required to mention the Aadhaar number in the forms for reporting birth and deaths, per a 2014 circular by the Office of the Registrar General, Ministry of Home Affairs. The Centre also allowed the RGI on June 28 to perform Aadhaar authentication during births and deaths; the UIDAI in 2021 announced plans to enrol newborn infants into the programme.

Any other amendments?

The Bill expands the demographic scope, amending the word “oldest male” to “oldest person” to refer to the individual responsible for providing information. It also accommodates “non-institutional adoption,” “child born to a single parent/unwed mother from her womb” and “orphan, abandoned, or surrendered child in childcare institution”. Individuals or institutions withholding information will incur a penalty of ₹1,000 per birth or death. An amendment to Section 12 states concerned authorities will be required to issue birth and death certificates within one week.

The proposal also mandates that medical institutions provide “a certificate as to the cause of death to the Registrar and a copy to the nearest relative.” Death registration in some States was disrupted post-2020, experts note.

Why does India want to change the registration process?

A dynamic ‘super database’ is being viewed as a Gordian knot to solve for administrative and policy hiccups. The U.N. Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner (OHCHR) has highlighted that streamlining birth and death registration processes contributes “to higher registration rates and increased coverage.”

For one, a compliance problem sits at the heart of birth and death registration. The United Nations called a functional CRS “the best source of information on vital events for administrative, demographic, and epidemiological purposes.” But a 2021 report on CRS found the database was only sporadically updated. A study published in PLOS One, studying Bihar’s use of CRS, found registration challenges due to a lack of investment, poor delivery of services at the registration centres, limited computer and internet services. People narrated accounts of taking off time to stand in long queues at offices, without access to shade or water. “Inadequate knowledge [about procedures and benefits] and attitude of community members” influenced registration levels.

Registering deaths presents a unique challenge due to a lack of monetary incentives and cultural norms, more so for women and infants. A study examining NFHS-5 data found “the likelihood of death registration was significantly lower for females than males”; one reason was that women’s deaths don’t accrue property benefits. Poor compliance creates a data gap, allowing for misguided policies and pushing of people into blind spots.

Two, an updated, timely and accurate database paints a clear picture of a population’s needs, estimates trends, identifies the target group for public welfare policies and influences long-term healthcare uses. Researchers flagged that the lack of “complete and timely death registration data” on India’s COVID-19 deaths prevented accurate measures of mortality, and “potentially masks the true extent of its impact in some States more than others.” Experts have argued the Census delay also creates a black hole of critical estimates of poverty, hunger, education, healthcare access, allowing the ruling BJP to overestimate the impact of their policies.

The Union Government previously experimented with SERVAM (a Unified Beneficiary Database) which interlinked the NPR, birth and death registration database, the Socio-Economic Caste Census, the PDS, NREGA, pension and LPG —with the objective of avoiding duplications and efficiently targeting beneficiaries.

Experts have pointed similarities to MHA’s National Intelligence Grid (NATGRID) project, which proposed interlinking 20 population databases as a counter-terrorism measure in the aftermath of the 26/11 Mumbai attacks. In April this year, The Hindu Businessline reported NATGRID would collate information from passports, PAN cards, NPR, vehicle registration, other databases to offer real-time 360-degree profiles of individuals to Central and State agencies.

Also read: Close watch. NATGRID to turn lens on digital print of people, firms

States including Andhra Pradesh and Telangana have undertaken real-time governance (Telangana’s Aadhaar-voter ID linking exercise resulted in over 20 lakh voters being deleted from the base, activists pointed out).

What do experts say?

The OCHCR notes that highly automated, digitised processes (similar to those proposed under the RBD Act) risk excluding individuals “unable to present standard identification documentation”, and greater decentralisation leaves people vulnerable to exploitation by “those facilitating the registration process.” The 2022 survey in Bihar found that CRS staff demanded bribes for providing certificates which are available free of cost.

Moreover, inaccurate data plagues the system; attempts to link Aadhaar to voter ID cards resulted in 55 lakh voters being deleted from the system, per media reports, and scams have been organised around issuing fake Aadhaar cards. Names of more than five crore workers were found to be missing from the MGNREGS scheme, the government told Lok Sabha this week. The NRC, which will tap into the database of NPR under the Citizenship Rules, 2003, left out more than 19 lakh people in Assam during the pilot exercise. Tying birth and death registrations with other demographic repositories risks widescale exclusions and misuse of data, experts flag.

India currently doesn’t have robust privacy and surveillance law. Experts have voiced concern that without a data Bill, information registered for one database can be utilised for another reason, without the individual’s explicit knowledge or consent. “What we have here is the proliferation of our identity information across government databases, allowing the creation of complete profiles of the population,” Srinivas Kodali, a researcher on digitisation, wrote in a media outlet. “There is no law at the moment to allow this or any of the other 100 databases for which the government collects data and shares it with the surveillance complex.”

A 2021 investigation found several instances where CRS was compromised, with the login IDs and passwords available in the public domain for sale at ₹2,000. This year, vaccine portal CoWIN’s data was breached, with a Telegram bot spewing out personal details like name, Aadhaar and passport numbers of people.

A unified database stands as a big Jenga pile: a security breach that threatens an individual block’s safety (be it Aadhaar or birth and death registrations) can cause the entire tower to fall.