A sense of trepidation accosts the arrival of Formula 1's incoming cycle of regulations. While the birth of F1's 2026 generation has been admittedly problematic, with genuine concerns raised throughout the development of the new rules, many have tended to err on the side of caution in their predictions.

Of course, the landscape will change and it'll be a very different F1 that we need to get used to. It might be bad, it might be good - ultimately, it'll only ever be subjective. If you weren't a fan of the 2022-25 cars, then the characteristics of the new machines might float your boat; if you want simplicity, however, then the array of new things might prove challenging to enjoy.

But if the racing is good, will we really care about all of that?

For some, the new rules will require some level of understanding - and that's something we'll aim to provide here. For those who have a bit more of a grasp of what the technical intricacies entail, there might be a nugget or two of something new that can be extrapolated and applied to this year's viewing spectacle. After all, some information circulating around the internet has been a little bit misleading - hopefully, this offers a little bit of clarity about what next year has to offer.

Aerodynamics

Active aerodynamics: F1 now has both front and rear wings that move in response to the drivers' command on the steering wheel. In effect, it's essentially the drag reduction system used from 2011-2025 at the rear, paired with something similar to the moveable front wing seen in 2009.

Its use cases, however, are not the same as DRS. Instead, each circuit will be designated zones where 'straight mode' can be used, with 'corner mode' to be used in every other location.

Watch: 2026 Formula 1 Technical Regulations Explained

When 'straight mode' is available, the front and rear wings will change alignment and move to a lower angle of attack. This will reduce the overall drag, allowing potentially higher speeds along the straights. Everyone will have access to this upon entering the defined 'straight mode' zones. As a driver approaches a corner and lifts off to brake, the car will re-enter 'corner mode' - ie. the wings will return to their higher downforce state.

There will be challenges to this beyond simply providing an actuator to control each wing. Teams have had to perfect flow reattachment with their DRS affected wings for some time, and in creating a trade-off between wings that provide high downforce in standard conditions and trimming off more drag when activated.

Ensuring that flow can attach itself to both wings quickly under corner mode will ensure that the driver has maximum stability for both braking and corner entry. Without the prompt reattachment of airflow, a driver would not have the necessary grip for the corners.

Flat floors: The underbody loses the Venturi tunnel (ground effect) aerodynamics seen from 2022-25 and returns to a variation of the 'flat' floors used from 1983-2021.

Overall, the new floors will produce considerably less downforce. The 2022-25 floors operated on a principle where, at the floor's smallest area, the airflow was accelerated to produce an area of extreme low pressure. The high-velocity, low-pressure flow underneath created considerable downforce, resulting in drivers being able to take many of the high-speed corners seen on the F1 calendar at full throttle.

The new floors do not have capacity to do this, and rely on the expansion of the airflow at the diffuser to generate the downforce. Before 2022, teams were experimenting with rake - in other words, running the front of the floor lower than the rear - in an effort to produce that acceleration and expansion of airflow to produce more downforce.

Flat floors were originally mandated in 1983 when ground effect aero was banned the first time around, resulting in a wide variance of car designs - from the dart-like Brabham BT52 and Tyrrell 012, the longer-sidepod Renault RE40 and Lotus 93T, and the Coke-bottled McLaren MP4/1C.

Powertrains

Composition: The combination of power unit components has changed slightly from last season. A 1.6-litre V6 turbocharged internal combustion engine remains as the centrepiece, rated at circa 400kW (536bhp), and complemented by a more powerful kinetic motor (MGU-K) which produces 350kW (469bhp). It's not entirely the 50:50 split advertised, but it does give the teams much more to uncover with regards to efficiency in their electrical components.

The MGU-H, the motor unit attached to the turbocharger under the previous regulations, has been removed. This was largely employed to pull energy out of the turbine when off-throttle, and to spool it back up again to eliminate the effect of turbo lag.

Boost and recharge modes: This is effectively what we've already seen with energy deployment under the previous regulations, but with a bit more manual interface. Teams generally mapped the energy recovery systems (ERS) to deploy and recharge at certain times, although drivers could change those maps depending on the scenario.

It was not uncommon for drivers to use the 'overtake' button on their steering wheels to be more aggressive with their ERS deployment out of corners and along the straights, whether in attack or defence, but the nomenclature here has been reserved for something else - hence the universal use of 'boost' and 'recharge'.

Drivers have generally been able to affect the rate of charge too, whether through power unit maps or manually, but there will be more onus upon them to do so manually to ensure the maximum uptime of the full 350kW allowance.

Overtake mode: The replacement for DRS, effectively a push-to-pass mode that keeps a car at the maximum 350kW for longer.

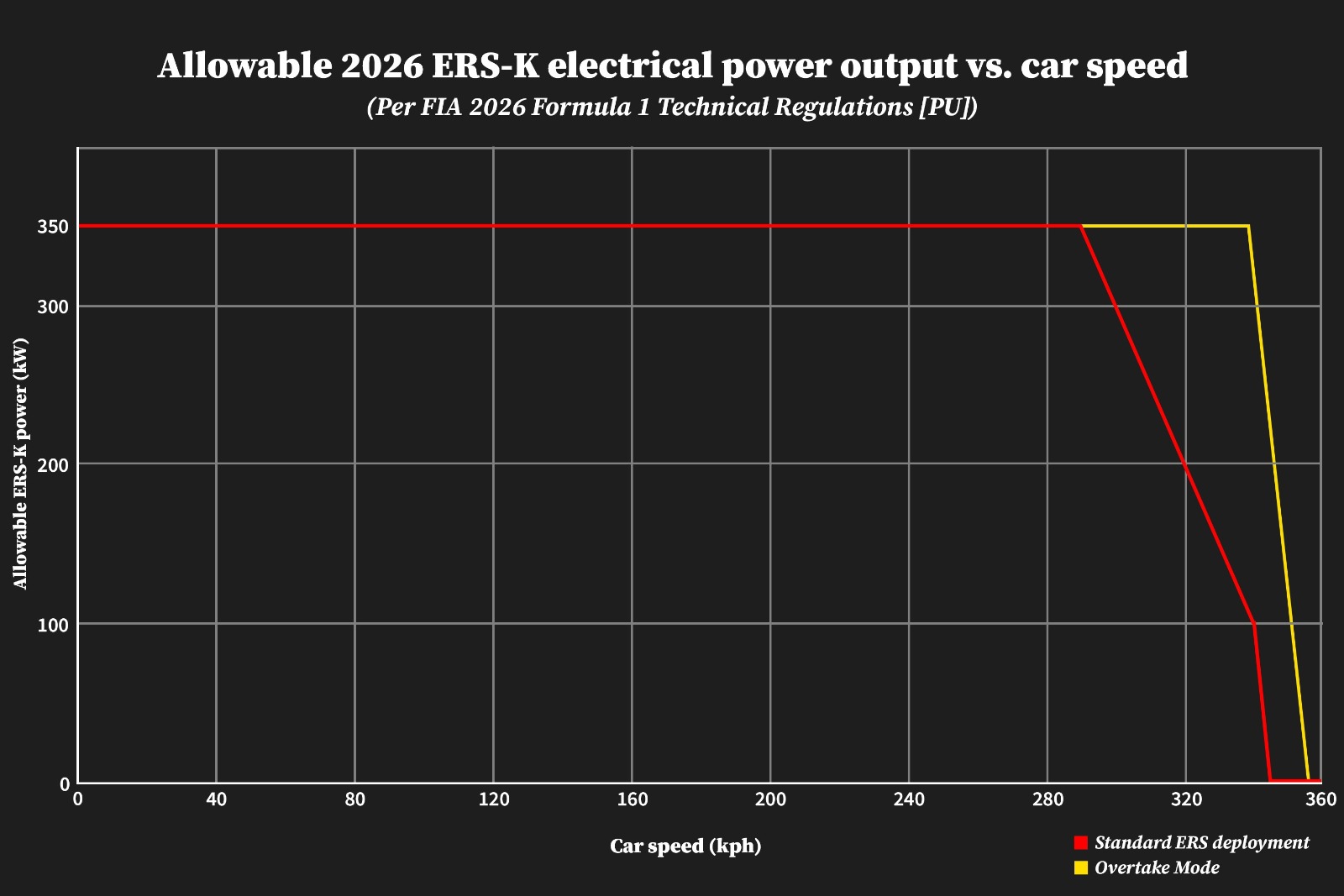

To assuage some of the fears that F1 cars would run out of useable battery before the end of the straights, the FIA implemented a series of additional features - active aerodynamics being one of them. It also introduced a rampdown rate for the MGU-K, effectively a gradual decay in the amount of useable electrical power at higher speeds - starting after 290kph (180mph) and eventually hitting zero at 355kph (221mph).

Overtake mode can be applied at the designated zones on-track, so long as the car is within one second of another - as per the allowed use with DRS. The formula to calculate the rampdown here is different, allowing the car behind to operate at the full 350kW of power until 337kph (209mph), where it then begins to regress to zero kW at 355kph (221mph).

In effect, the car will be able to reach its maximum velocity sooner than the car ahead. It remains unknown whether this will provide a similar delta to DRS in effect, and the extra energy used will not necessarily allow the drivers to use it on every lap; it's up to them to plan their recharge points and simultaneously ensure that they remain within one second before deploying the overtake mode.

Sustainable fuel: All 2026 cars will run on a fuel determined to be 100% sustainable by the FIA, using the defined "advanced sustainable components". As such, any biofuel elements must be a "second-generation" biofuel, where the sources come from non-food biomass or municipal waste to avoid cutting into the global food chain. Any high-cellulosic arable waste that cannot be digested by humans can be used in a fermentation process to produce the requisite hydrocarbon fuel, as can specifically produced crops grown purely for biofuel purposes.

Non-biological origin fuels can also be used, known as synthetic fuels or e-fuels. This is where the fuel is produced using sustainably-sourced hydrogen gas and carbon monoxide (which can both be produced from the electrolysis of water and carbon dioxide respectively) and placed in a reaction chamber with a catalyst to create fuel.

In this case, carbon capture methods can theoretically make this a carbon-neutral fuel - but the efficacy of such methods is disputed, given the high levels of energy needed for direct air capture applications.

Read and post comments