The power of compounding is an important concept that investors need to understand. Investing consistently and starting earlier in your life (i.e., age 25) can result in hundreds of thousands more dollars in your investment account than if you were to start 10 years later.

While quite a few personal finance pundits have suggested that a stock investor can expect a 12% annual return, when you incorporate the impact of volatility and inflation, 7% is a more accurate historical estimate for an aggressive investor (someone primarily invested in stocks), and 5% would be more appropriate for someone invested in a balanced portfolio of stocks and bonds.

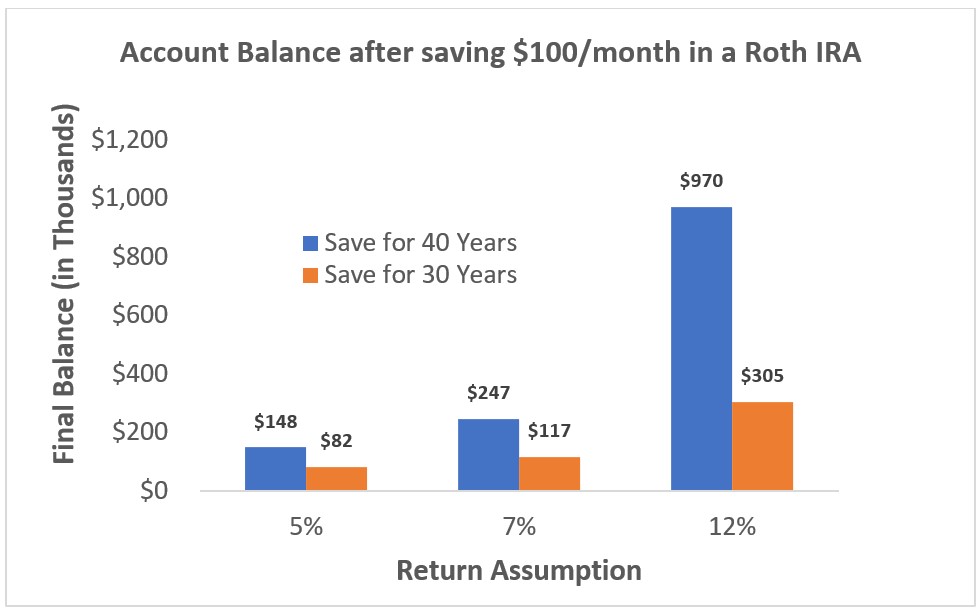

The chart below illustrates how dramatically different account balances might be using different return assumptions, assuming you save $100 a month in a Roth IRA.

While it’s true you can achieve a balance of nearly $1 million if you save $100 per month for 40 years assuming a 12% return, that’s incredibly unlikely when you factor in market volatility and inflation. In reality, if we assume a 7% return, which even still may be a touch optimistic, it will require saving $400 a month, or four times as much, to generate that same $1 million.

In other words, not only is 12% an incredibly unrealistic assumption using historical data, but it’s also actually quite dangerous since it could result in radically undersaving for retirement.

So, where does 12% come from?

Investing is a fundamentally uncertain exercise. No one knows what the markets are going to do in the future, and so a common starting place is to look at historical U.S. market performance.

The U.S. has had one of the best financial markets in the world over the last century, and while this may paint an unrealistic picture about future market performance, it does provide some useful context about expectations. One of the most commonly used historical datasets is the Stocks, Bonds, Bills, and Inflation (SBBI®) series.

The SBBI data spans 98 calendar years, from 1926 to 2023. If we take the simple average of the historical returns over this period, you’d get 12.2%. That’s the 12% everyone always talks about!

The problem is, even if you’d invested in that exact same stock market index over that period, you would have actually earned 10.3% (not 12.2%), due to the effects of volatility. Even the 10% estimate doesn’t include inflation, which has averaged about 3% a year, further reducing the historical return closer to 7%.

Tack on things like fees and taxes, and even 7% is probably a relatively high long-term return assumption for a portfolio, especially based on market forecasts today. Had you been invested in a balanced portfolio, your return after considering volatility and inflation would have been closer to 5%. I’ll dig deeper more next.

Volatility is not your friend

The simple average, or arithmetic average, is calculated by adding up some number of values and dividing by the number of observations. So, the 12.2% historical long-term average return is estimated by summing up all the historical returns (which equal 1,191.81%) and dividing by the number of observations (98).

The problem with this approach is that it doesn’t accurately reflect what happens to wealth when you experience a negative return. Simply put, negative returns hurt long-term performance more than positive returns. Here’s an example: Let’s say you have an initial portfolio worth $100 and it achieves a return of +100% in the first year and -50% in the second year. The simple average return would be +25% (+100% + -50% = +50% / 2 = +25%), suggesting you’d have a final balance of around $150 at the end of the two-year period. Sounds fantastic, right? However, in reality your final balance is the original $100, and your realized return is 0%.

How could that be? Well, if you have $100 and the portfolio return is +100%, you now have $200. If the return is then -50% you’d lose half the balance and be back to the original investment of $100. That’s because negative returns hurt more than positive returns when it comes to building wealth, and why you can’t use the simple average as the expectation for long-term performance.

A better metric is what’s called the compound return, or the geometric return, that explicitly incorporates the impact of volatility on wealth growth over time. I won’t get in the weeds here, but here’s a reference if you’re interested in learning more about the calculations. What’s important, though, is that using the geometric return, the growth rate of an investor’s portfolio would not have been 12% historically, it would have been closer to 10%.

Have there been 30-year periods where the geometric return has been higher than 12%? Of course! The highest average 30-year geometric return was 13.7%, so it’s definitely possible. At the same time, though, the lowest average 30-year geometric return has been 8.5%, so it’s been lower as well.

Inflation is also not your friend

The second important consideration that the 12% long-term return estimate ignores is inflation. Inflation is simply a measure of how a set of goods or services changes over a certain period. The most common estimates of inflation in the U.S. are based on the consumer price index (CPI), calculated by the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The long-term inflation rate from 1926 to 2023 has been about 3%. This means that the price of goods and services have increased on average by 3% per year over that 98-year period. When thinking about the long-term growth of wealth, we need to back out inflation, since we want to buy things in today’s dollars. That means the 10% geometric return is really more like a 7% return when we account for inflation.

Using the return before inflation, called the nominal return, effectively assumes that everything is going to cost the same in the future, which is incredibly inconsistent with historical evidence and future projections around inflation rates.

Other considerations

The initial 12% return drops to 7% when considering the implications of volatility and inflation, but there are other considerations that could cause it to drop even further. This includes fees, taxes and asset allocation.

First, let’s talk fees. The index return doesn’t account for any sort of historical fees, but investing has never been free, especially if we go further back in time. The Vanguard S&P 500 investor index had an expense ratio of 0.43% back in 1976. The cost of investing was even higher if we go back further in time. While these costs have come down significantly, almost approaching zero, they definitely haven’t been zero historically, which would have reduced returns realized by investors.

Second, we can’t forget about taxes. Taxes are going to reduce the compound return for individuals, especially those who are investing in a taxable account. This is something known as tax drag, and it can be especially significant for investments with higher levels of income or turnover.

Third, asset allocation will have an impact on returns. Very few retirees should be invested entirely in equities. A decent target for how much of your portfolio you should have in equities is 110 minus your age. So, at age 65, a 55% equity allocation is a reasonable starting place. If you consider a balanced portfolio of 50% stocks and 50% bonds, the 7% geometric after-inflation return falls to 5%.

Now what?

While 7% is a far more accurate reflection of the long-term return of investing in equities, and 5% for a balanced portfolio, it’s important to note these historical returns are not necessarily consistent with forecasts. As noted previously, the U.S. has had one of the best financial markets historically, and I worry that future returns could be more similar to our international peers. For example, the PGIM Quantitative Solutions Q4 2023 Capital Market Assumptions for the future inflation-adjusted return on stocks is closer to 5%, which is significantly lower than the historical long-term average.

Using lower expected returns could result in higher required savings rates in accumulation or lower spending levels in retirement, but it’s important that assumptions in any financial plan be as reasonable as possible, and to reiterate, a 12% return assumption on stocks isn’t just unreasonable, it’s dangerous.