September in Melbourne finds me melancholy. The sun is bright but the wind is cold; the blossom is out but the winter sads hold fast.

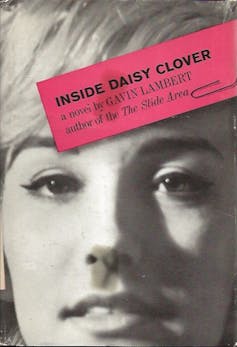

It is around this time that I return to my Lamberts – three quiet, perfect books by Gavin Lambert, the English film critic who decamped for Los Angeles in the 1950s and chronicled the beautiful and the tarnished with equal clear-eyed, curious affection. The books are: The Slide Area (1959), Inside Daisy Clover (1963) and The Goodby People (1971). Along with Running Time (1982) they make up Lambert’s “Hollywood Quartet”.

If I’m melancholy around this time, I am also psychically open. September is for tarot spreads and house moves. It is in this winsome waiting month that I am most able to transport myself into narrative – and there is no place I would rather roam than Lambert’s L.A., with its mouthy child stars, lonely screenwriters, “failed mystics, rootless sun-worshippers [and] exiles from the harsher realities of a different civilisation”.

Read more: Blonde: Joyce Carol Oates' epic Marilyn Monroe novel captures the violence of celebrity myth-making

Inside Daisy Clover

I came to Inside Daisy Clover first. I discovered it in when I was living in England, and I’m sure the when – being overseas, feeling like a true citizen of the world – has deepened my attachment to it.

But there is also Daisy’s voice – tough, kooky and full of longing. Daisy is an adolescent fantasy figure, “pushing fourteen”, precocious and hectic. She lives with her mother “The Dealer” (so called because she usually has several games of solitaire going at once) in their trailer at Playa del Rey, “a cockeyed dump between two other cockeyed dumps called Hermosa Beach and Venice”.

Daisy’s pastimes include keeping an eye on her mother, moonbathing, and thinking about S-E-X, but what she really loves is the recording booth at the old pier at Venice, “I pay my twenty-five cents […] and I go inside and face this old man with a nervous twitch who works the machine and I SING.”

At first, Daisy keeps her singing to herself, but as The Dealer grows more unhinged she turns outward. When Daisy enters the Magnagram Studios talent contest, Raymond Swan, studio boss, and his icy wife Melora, send a limousine.

Daisy’s social skills are negligent. She turns up to her screen test for Little Annie Rooney wearing “a sickening little white number with too many flounces”. She faints during her audition, shocked by the heat and bright lights, but is somehow able to transcend the moment and blow everyone away. A Star is Born!

Things move swiftly. Daisy’s hated sister Gloria steps in as her guardian and the Dealer is put in a sanitorium. Daisy becomes the “Orphan Songbird”. Production begins and it’s all work-work-work and sometimes Benzedrine. First one film, then another. Daisy has little agency, and no friends aside from her Magnagram “family” – the Swans, her dodgy director, assorted film crew, and her literature teacher, Caroline, who tells her “a person with imagination is also a person with some degree of madness”.

At her first company Christmas party, Daisy meets up-and-coming actor, Wade Lewis, who is older, alcoholic and in the closet. His preferred methods of communication are Bessie Smith records and grand gestures. “Refuse to do it their way,” he says, against the Swans and the system. “Their way is an insult to human dignity.” Daisy pursues Wade, even though it means losing everything. But the way she sees it, she already has lost everything.

For much of the novel, her dream is simple – freedom – just her and Wade and the Dealer in a house by the beach. It is only when Wade abandons her after their “Hollywood” wedding that she realises a new dream is in order. And then it is only when she abandons the movies, the life that has been built around her talent, that she finds freedom and becomes herself again.

“In America,” Lambert wrote in The Slide Area, “Illusion and reality are still often the same thing. The dream is the achievement, the achievement is the dream.”

Read more: Natalie Wood: Nothing can bring back the hour of Splendor in the Grass

Hollywood on the cusp of change

Inside Daisy Clover perfectly describes a moment in time, when Hollywood was on the cusp of change, and the new moralities of the 1960s were edging out the old ways. Lambert was there for the end of the studio system. He left the bleak of England to become Nicholas Ray’s protege in 1955, and went on to a long career as screenwriter, novelist and biographer.

His friend and subject Natalie Wood plays Daisy in the film adaptation of Inside Daisy Clover – it’s hammier than I want it to be, but I’d still have it over nothing – and Robert Redford plays the elusive Wade. Redford was reportedly not happy about his character being depicted as strictly gay.

In the film Wade simply disappears, but in the novel he is found living with his boyfriend in Mexico; later they run a hotel in Tangiers. Lambert ended up in Tangiers too, leaving L.A. because he felt it was time: he’d recieved a “message”. When asked if he considered himself an exile of L.A., he replied, “I consider myself an exile period.”

But I have found a kind of home in his books and in his characters. It is because even if they are lost, they are not resigned. And because no matter what happens to them, they are always seeking. Lambert’s description of the city also fits the dreamer’s pattern:

something unfinished yet always remodelling itself, changing without a basis for change […] So much visible impatience to be born, to grow, such wild tracts of space to be filled …

At her most lost point, Daisy Clover asks herself, “What’s the point of it all? Where’s it all going to end?” As with most things, it ends where it begins. Or rather, it ends with a metaphor of a shell Daisy’s been carrying around. It echoes long after she puts it to her ear, reminding her “the waves were always breaking somewhere else as well”.

For some people, to stop, to settle, to accept, is the same as dying. There is always something over there. The promise of it tantalises.

Simmone Howell does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.