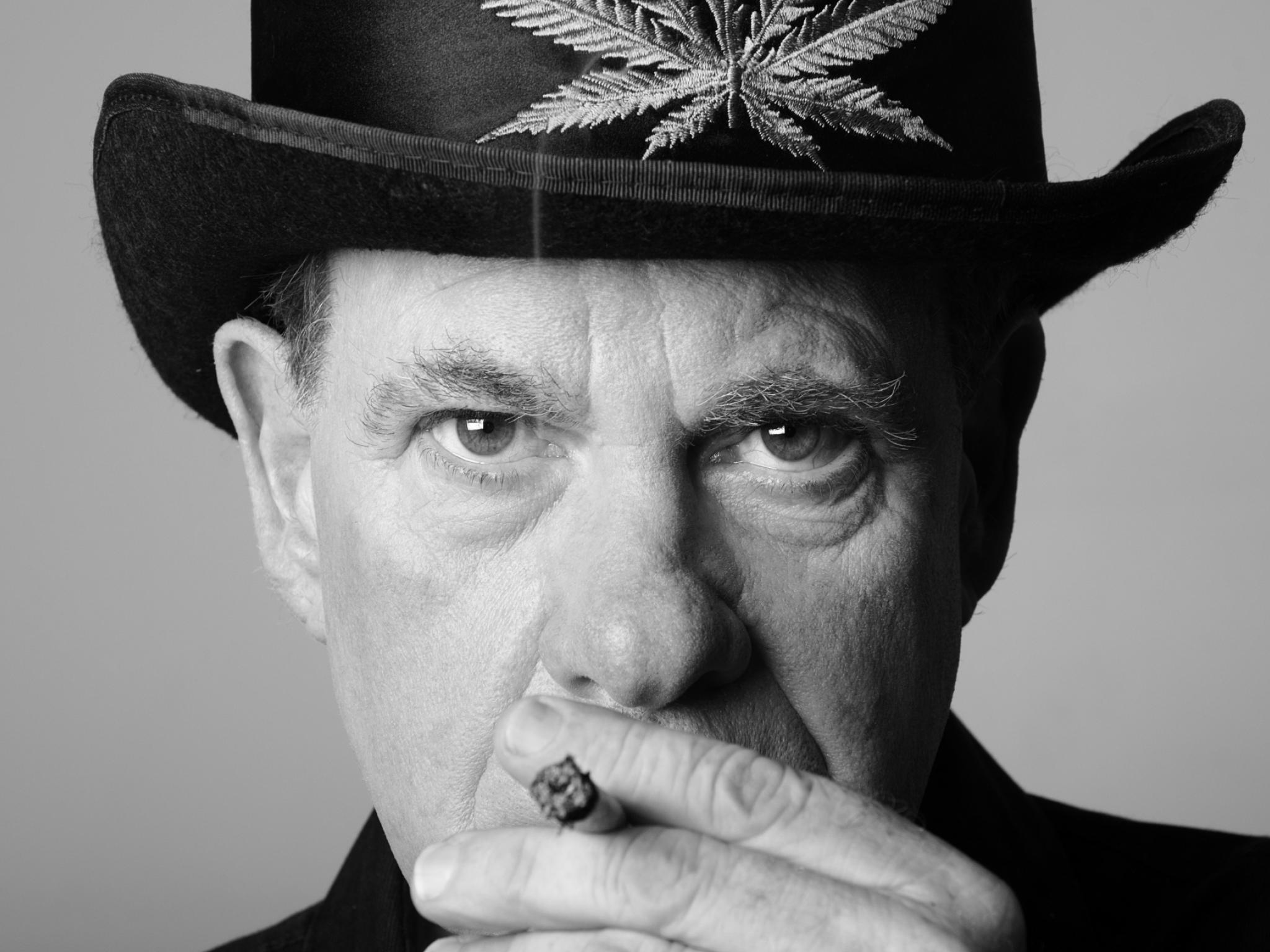

By Nicolás José Rodriguez via El Planteo.

"The ganja guru," Ed Rosenthal, is an international authority on cannabis horticulture, as well as an author, educator, social activist and legalization pioneer.

Co-founder of High Times magazine, Ed is a professor at Oaksterdam University in Oakland, California, and author of "Ed Rosenthal's Marijuana Grower's Handbook," a book that, since 1978, has inspired millions of people to learn the best marijuana growing techniques.

In 2002, Ed was prosecuted and his case influenced public opinion in favor of state medical marijuana laws. At the age of 77, the professor and author puts into perspective the advances of the home cultivation movement, raises some questions inherent to the industry and offers a few clues to think about the future of legalization.

Everyone should have the right to grow their own marijuana

Since Ed began championing the cause of home cultivation, 50 years ago, the movement has achieved some degrees of freedom in terms of where we can grow our cannabis and under what rules. However, he believes this is an incomplete revolution and that there are still many rights to conquer.

The horticulturist explains that there are several state laws in the United States that allow people to consume and buy, but not grow on their own cannabis. For example, in the state of Washington, where people cannot currently grow, but can buy cannabis in licensed dispensaries.

Why home cultivation?

First of all, home cultivation is about reclaiming pleasure, collective and individual enjoyment. "Growing a plant is a pleasure," says Rosenthal.

Another reason to support home cultivation is a question of health: "When we grow we know what we are consuming and thus we can avoid consuming pesticides, herbicides or fertilizers".

And, finally, there are reasons for social justice. "It is much cheaper (and therefore more accessible to everyone) to grow cannabis naturally, rather than going out and buying it," Ed adds.

"Marijuana use may not be addictive, but growing it is. There are people who don't use marijuana anymore, but they still like to cultivate the plant. Growing is very addictive, and probably, the reason is that of anthropomorphism: marijuana has stages of growth: a vegetative stage, a reproductive stage, like human beings."

From 'marijuana' to 'cannabis': the resignification of a plant

Since the late 1970s, the U.S. has seen an explosion of home cultivation and the cannabis culture has spread around the world. In part, thanks to the work of people like Ed.

Since then, the meaning of marijuana has mutated: stepping from being a countercultural revolutionary flag to being a commodity, a lifestyle, and a life-enhancing medicine, that stimulates productive, relaxed, and happy individuals who abide by the dominant social rules.

Ed finds it very interesting that cannabis has gone from being a pariah to being considered an essential product during the pandemic. And believes that, in part, this was due to a question of social control: if people were going to stay at home, the government understood that it would be much healthier for them to consume marijuana rather than alcohol.

Ed describes the expansion of cannabis culture internationally as a driver of global change. “Something similar to what is happening in the music industry”.

"Like with Seth Rogen smoking a joint on TV, how do you know where that kid can travel with his message? Everywhere, of course! There's an international aspect to the expansion of our movement and there's also a strong regional aspect."

The experienced horticulturist states that a particular gene pool can be grown in different areas because of its resistance to disease or other environmental conditions.

Varieties and cultivation techniques differ in yield by zone, and yields vary according to latitudes. All these aspects influence each region to develop different ways of relating to the plant and different cannabis cultures that contribute to legalizing the plant.

Legalization in perspective

Ed Rosenthal believes that the advance of legalization in California progressed as a matter of racial justice, on the one hand; and, on the other, as a cultural change that swept the entire country, starting in 1973 when marijuana was decriminalized for the first time in Oregon.

According to Ed, once marijuana was presented as a medical issue, "more and more people became familiar with it because more people were using it." General acceptance of marijuana grew and "reached the majority of voters some time in the late 1990s in California."

And he clarifies that "in Northern California, growers were notably absent in the push for legalization, a good portion of them wanted it to remain illegal to continue to have a market with inflated prices because of the risk of getting caught."

"It was a long-term process, with tipping points, it took 50 years, but society went from being two-thirds against it to maybe two-thirds in favor of it. Certainly a majority. And a good example of that would be Oklahoma, which is a very conservative state, voted for Trump the second time, but also 70% voted in favor of medical marijuana. This shows how, even in a conservative state, concerted effort can make change", he analyzes.

"I think there are a number of international companies that are trying to get now into various places in South America. This has its good and bad points, but there is no reason why cannabis has to be anything but regional," explains the "Ganja Guru."

According to Ed, there is no reason why you can't produce cannabis in cooperatives or have both home growing, small-scale production and industrial production.

"My main concern is that people have the right to grow their marijuana. The closer the consumer is to the flower, the easier it is for cannabis to stay regional. That's why I don't mind giant industrial cannabis companies, as long as people have the right to grow their own at home."

California: a beacon for the industry?

The state is often touted as a beacon for the industry. However, Ed rejects the idea of making California a model for-export .

Laconic, the septuagenarian author states, "I don't agree with the idea of California being a beacon for the industry. California is not a recipe or a silver bullet."

Rosenthal explains that California has made it very difficult to enter the industry.

First, many counties don't allow the industry at all and don't allow outdoor home growing, while state law restricts home growers to six plants.

"So if you want to grow a bunch of small plants (in California) you're breaking the law, even if they don't produce much. And there are a lot of reasons why people might want to grow small plants. It's a matter of space and it takes less time to do it. Also, people need more varieties for their own use."

Ed explains that there is also a problem of limited licenses, which makes ordinary people and companies compete for them, and believes that marijuana "should be an open market".

He offers an example: if people pass the hygienic and other business requirements, "they should be able to open a cannabis store. I don't think everyone should have to pay millions for licenses. This creates an inequitable situation and makes it very difficult for people to enter the market."

Another problem in California, according to Ed, is the method for counting plants that determines how much people can grow, and argues that "counting the number of plants is a totally unscientific, unproductive and useless method that should be eliminated."

"The idea of labeling plants is ridiculous -can you imagine if we did that with corn or wheat or something like that? I'm sure in the future these methods will be eliminated because they're stupid and they slow down the industrial use of the plant, it triggers every cost you can imagine and it's bad for the environment."

Ed explains that often in California, people are forced to grow larger plants that are very inefficient and, again, like a good teacher, he clarifies with an example:

"Let's take a typical plant. You know, it's five feet tall, let's say. It spends a lot of its time vegetating, growing a lot of leaves and branches, which are not harvested. So, it spends a lot of time in a useless state for us. Smaller plants make it possible to shorten flowering times and ensure a steady home supply of cannabis for the user."

As to which method of recording and measuring crops he recommends, Ed advises concentrating on the canopy of the plants, the shade casted by the plants on the ground: "California should rely on science to measure the number of plants. That is, on the amount of space and the amount of light it receives under certain environmental conditions and surface area."

Cannabis, Social Equity and Mobility between Social Classes

In addition to regulatory and technical issues, Ed points out that California still owes a huge debt to racial minorities and social classes that have been historically criminalized for cannabis use and points to social equity programs that seek to enable small businesses to enter the industry.

"If there was ease of entry into the market, there would be no need for an equity program."

Simply put, Ed tells us that if people had enough money to get a license similar to a grocery store, in general, it wouldn't be a restricted situation. They would just do it. "But here they're saying, 'oh no,' only a certain number of licenses, 'sorry,' we only have 12 licenses available and no, no, no license for you."

Rosenthal believes that, part of the reason many states proceed this way, is because of a tax issue, as it's easier to tax a few large corporations "than it is to go out and collect from a lot of small farmers."

Ed points to "bureaucratic requirements that are designed to protect people who are already in business and make it very expensive to open a cannabis store."

In fact, licenses can cost anywhere from hundreds of thousands to millions of USD.

Rosenthal calls these license programs a "social inequity programs," adding, "In Nevada, for example, just to apply, you need USD 500,000. That's part of the inequity program. And it's a class issue. It's about a difference between social classes that the regulators don't understand."

He warns that often the economic need of some people enrolled in social equity programs allows them to be used as fronts by more powerful investors who remain in the shadows.

"I'm not saying that social equity is bad, but it happens that sometimes these programs include people who opportunistically find supposed partners who have been harmed by criminal laws, to put together purported social equity ventures, to then, buy them out as soon as is legally possible."

To reverse this process of "social inequity," Rosenthal proposes more and better training of the industry's workforce in the state: "If they really wanted to achieve social equity in this industry, what they should be doing is funding internship programs and entrepreneurial training."

Ed's idea is not new. Basically, the professor argues that the industry should serve the social ascent of the industry's workers through investment in education. This, for him, means social equity in cannabis and a contribution to social justice that is possible.

"My idea is that people really move between social classes."

"If what you really want to do is to achieve progress, to move society at large forward, what you need to do is to make the entry into the marketplace not as arduous and costly as it is now and give tools to producers to improve their business. This is a business and everyone who wants to have it should be licensed and pay taxes."

Ed refers to licensing on an ongoing basis as a possible way out of the current scheme.

"Now in California they've licensed home cooking so people can sell baked goods or, you know, different things. Well, why not do the same thing then for cannabis?". He adds, "This would prevent that when people buy cannabis, a lot of that money would leak out of the community."

Social classes and unionization in the cannabis industry

Rosenthal believes that unions should have a place in cannabis, as there is a lot of labor in the sector.

"And even with mechanization and automation, there will always be a certain amount of labor. And I think it would be good to have unions in both the production and retail phases of cannabis."

Rosenthal believes that workers will have fair pay and working conditions while preventing the exploitation of migrant workers who come to California with the illusion of earning unthinkable sums in their home countries. And often, find themselves living in exploitative conditions, doing monotonous, repetitive work with little rest under no health and safety standards.

Cannabis appellations

In the 1970s, growers went to Northern California to forge (for better or worse) the first cannabis region widely recognized in pop culture. A region that is considered a mecca of self-management and life outside of the conservative white American suburbs typical of the post-war era.

One of the strategies in vogue in California to enhance the value of cannabis products from Northern California are the regimes of appellation of origin -as with wine.

Producers in Mendocino county, in the northern part of the state, are preparing regulations to make their cannabis a distinct product that takes advantage of the region's growing cannabis reputation to penetrate market niches.

In this regard, Rosenthal considers the system "controversial". "Because producers tend to change the terroir, the native soil in which the plants are grown".

Given that they alter local soils, why should they have that designation? On the other hand, Ed says that despite what most growers think -that they have "native" varieties or landraces, in reality, these strains are not landraces, and are constantly being manipulated.

"The reason growers arrived in the 'emerald triangle,' in California, was not because of the good soil or the wonderful climate, which they definitely don't have. If you really want to grow good cannabis, what you want is lots of sunlight, UV radiation and a good amount of heat. You don't need to come to Humboldt."

"You don't see farmers running to the mountains upstate to grow corn or vegetables. The only reason people went up there is because of the difficult interdiction by the police. Many of them have done illegal things as far as the environment is concerned, like leaking nutrients into the soil and leaching fuels into the watershed which kills native vegetation."

He says with a smile, "This is going to get me a lot of hate, of hate mail.”

The Tomato Model

Rosenthal believes there should be room for everyone in the cannabis industry and explains what he calls the "Tomato Model”, a strategy for low-scale cannabis production.

The Guru explains that "there are international companies growing tomatoes and, in parallel, there are farmers grouped in regional forums, cooperatives, chambers and individual farmers or gardeners who can sell their tomatoes on the side of the road and can compete in the 'boutique segment' with an industrial tomato."

"More people grow their own tomatoes at home for their own consumption than all the industrial tomato groups combined. And I think, if we had smart regulations, that's what would happen in cannabis," he clarifies.

Ed says he doesn't mind that there are multinational industry organizations that certainly contribute to the advancement of the industry. But he clarifies that "this progress should not proceed amidst restrictions for individuals and home growers."

Continue reading:

- This Former Congressman Is Placing Big Bets On The Cannabis Industry

- Original publication: 2021-08-16