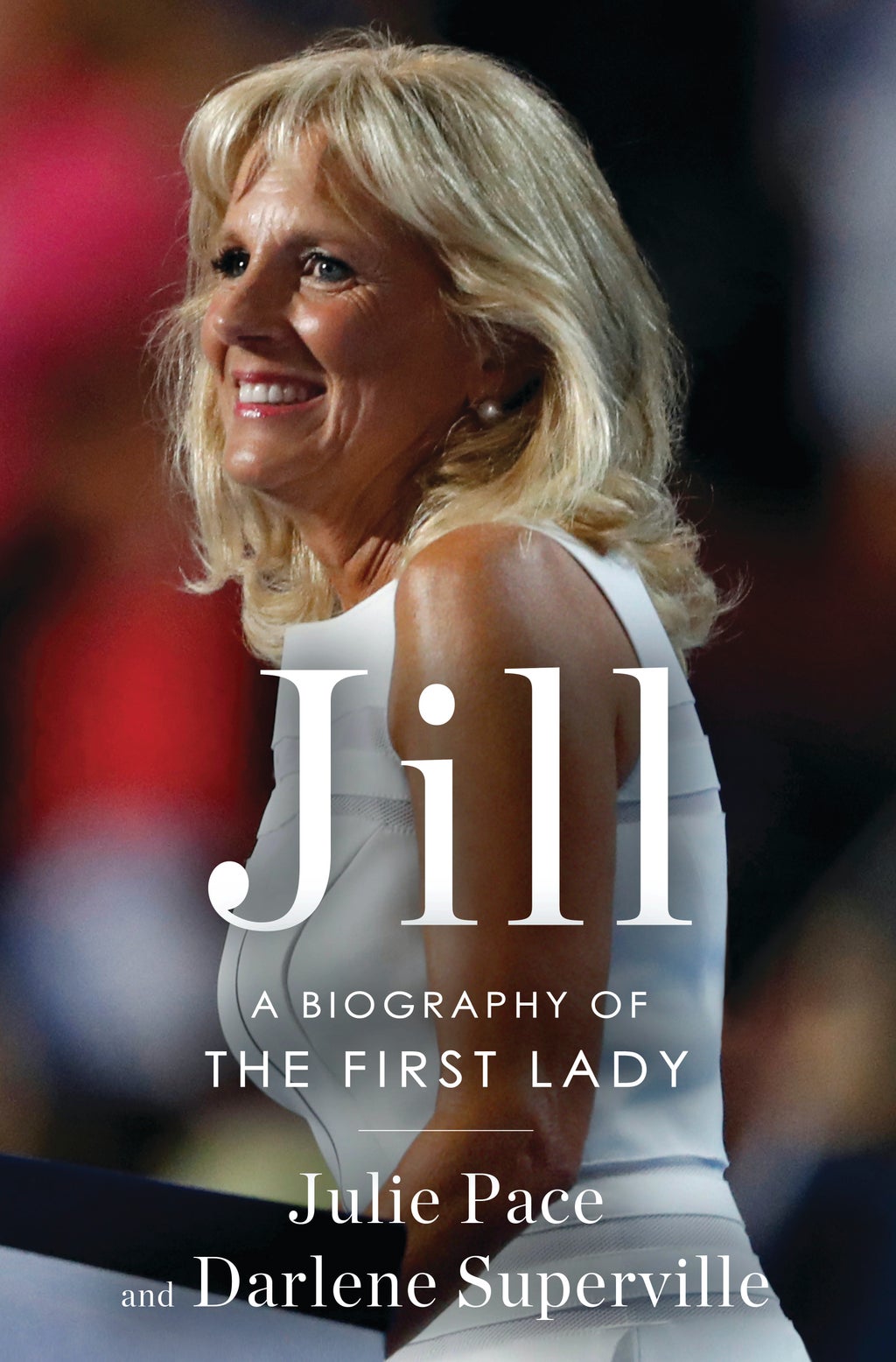

The following excerpt is from “Jill: A Biography of the First Lady,” by Associated Press journalists Julie Pace and Darlene Superville. The book details the life of Jill Biden. Superville covers the White House for the AP; Pace, a former White House correspondent and Washington bureau chief, is now AP’s executive editor.

___

Joe’s first Senate reelection campaign demanded Jill’s participation.

“It was a little overwhelming,” she said, the first time that Joe took her to a campaign event. A picnic at Archmere Academy, Joe’s high school alma mater, was one of Jill’s first political appearances as Joe’s wife. She was unprepared for the throngs of people. “I felt like I was being pulled and tugged every which way, literally.” Everyone wanted to talk to her:

Oh, meet my sister.

Do you know so‐and‐so?

Oh, did you meet this person?

I’m from Sussex!

“I can remember going home, going up into the bedroom and just shutting the door,” Jill said. “I mean I just had to breathe. It was just so overwhelming for me.”

But then she started to travel the state and campaign in earnest. “I would go to every senior center and have lunch with seniors,” she said. “I would go to coffees. I’d go to the state fair.”

Joe’s sister and campaign manager, Val, became Jill’s mentor, helping her practice her public remarks and patiently explaining various political organizations and key people she needed to get to know.

Jill was more at ease in smaller settings, where she felt like she could relate better to people.

She slowly started to get to know Joe’s colleagues in the Senate and their spouses. “They loved Joe and they wanted him to be happy,” she recalled. “I was just welcomed into the Senate.”

Three or four times a year, the sitting senators and their spouses would get together for dinner. The tables were a mix of Democrats and Republicans. “These were done to foster good relationships between the senators regardless of party,” Marcelle Leahy recalled. Jill began to forge friendships that would last for decades.

___

Joe’s electoral chances in the upcoming Senate race were bolstered by a guest appearance by President Jimmy Carter at a pair of Wilmington fundraisers in February 1978.

The first, a dinner in the glittering Gold Ballroom at the Hotel Du Pont, was formal but at Carter’s request did not require black-tie dress. Racks of lamb, seafood, and American wines were served beneath ceiling bas-reliefs of Helen of Troy, Cleopatra and other famous women. Guests paid upward of $1,000 to take photos with Joe and the president, and Jill helped work the crowds as they navigated the ballroom.

Following the dinner, Joe and President Carter attended an additional stop at the Padua Academy, a more accessible event. A thousand or so attendees, many of whom had been supporters of Joe’s since his initial run for the Senate, paid $35 to support his reelection bid, have a drink, and dance with fellow Delaware Democrats.

The evening was a necessary exercise in party unity. Although Joe had been the first senator to support Carter’s 1976 run for president, he had recently been critical of the administration. “They got to Washington and didn’t know how Washington worked,” he’d said. “The president is learning, but not fast enough.” Carter, for his part, paid Joe the backhanded compliment that he was “independent almost to a fault.”

Carter spent only 64 minutes with the Bidens that evening, but his visit helped Joe’s campaign bring in more than $60,000.

As the campaign year wore on, and political tensions across Delaware began to heighten, demands on Jill began to shift away from hostess duties. Joe’s rivalry with James H. Baxter, the Republican challenger, started to push her closer to the public arena.

Baxter attacked Biden as a “no-show” senator, running an ad claiming, “Biden misses 502 Senate votes.” Baxter’s main message to the public was that Joe, instead of representing Delawareans in Washington, was out wasting taxpayer dollars traveling on frivolous business trips. In truth, Joe had a typical attendance record for a senator.

Joe played into his opponent’s hands by missing an event sponsored by the Hadassah Women’s Zionist Organization that Baxter and other Delaware officials attended. Jill, Beau, and Hunter attended.

Baxter once again returned to his mockeries of “no-show Joe.” Ironically, Joe’s absence was due to a 10 p.m. vote in DC on a bill that he had co-sponsored. This time Baxter was criticizing him for not missing a vote.

Jill stood in as his protector.

“I just cannot let this go by,” she told the gathering. “I just can’t let you go out that door thinking that Joe just sloughs off down in Washington! Joe is a smart man and he knows which votes are important . . . If he misses a vote because it’s an amendment to an amendment, he’s made a good decision on that!”

Jill increasingly found herself in the local spotlight in the usual ways for a Senate spouse. She headed up Operation Reindeer, an event put on by the Mental Health Association that provided small gifts for the thousands of patients throughout the Delaware state mental health treatment system. And she signed autographs for people who bought copies of a cookbook that included a recipe for Jill Biden’s Chocolate Cake that benefited the Wilmington Hadassah.

After being married to Joe for more than a year, Jill was still registered as a Republican. Once the local papers found out, she told them that she planned on changing her party registration to Democrat. But she missed the deadline, meaning that if she wanted to vote in the Senate primary, it would have to be in the Republican contest, where her choice would be to help Joe’s main rival, James Baxter, or Baxter’s primary challenger, James Veneman. She voted, but would not tell Joe, the kids, or the press who she voted for.

On Election Day, Joe secured his Senate seat for a second time. He won with more than 93,000 votes to Baxter’s 66,479.

___

In the spring of 1978, Joe met a young lawyer, Mark Gitenstein, at a Senate hearing on the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) of 1978. Gitenstein detailed the work on intelligence overreaches by US government agencies that he had done for Minnesota Sen. Walter Mondale as counsel to the US Senate Select Committee on Intelligence.

Joe was impressed with Gitenstein’s command of the issue and invited him to speak privately.

Gitenstein thought Biden wanted to talk about the FISA issues at hand and concentrated on convincing Biden about what should go in the FISA statute. Following a period of civil rights abuses, and the classifying of citizens such as Martin Luther King Jr. as potential threats against the state, FISA and the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court were meant to be positive steps toward institutionalizing channels through which intelligence could be collected.

But Joe talked more broadly, asking questions and running Gitenstein through his paces. Eventually Gitenstein realized Joe was interviewing him for a job. Biden invited Gitenstein to dinner in the Senate dining room with his chief of staff, Ted Kaufman, Jill, and the boys. Gitenstein found the Bidens — particularly Jill — delightful.

“It was out of that evening that I came away saying, ‘You know what? I like this guy, and I like the way he treats his kids,’” Gitenstein said.

In those early years, sometimes Gitenstein would travel with Joe and Jill on official trips, and while Joe certainly wielded his own charisma in the right settings, it was Jill who brought the jokes and could cut a rug.

John McCain, the Arizona Republican who would later be elected to the US Senate and run for president in 2000 and 2008, was still in the Navy as a captain and acted as Biden’s Navy liaison on a trip to the Mediterranean. Joe would later tell a story about returning from dinner with the prime minister of Greece and finding Jill and McCain dancing on a concrete table in a taverna on an Athens beach. McCain danced with “a red bandanna clenched in his teeth,” wrote author Robert Timberg.

Jill eventually returned to teaching part-time. “They needed reading specialists in the state of Delaware, because Delaware was going through ‘deseg,’” Jill recalled.

School segregation had deep roots in Delaware. A local court case known as Gebhart v. Belton had been folded into the collection of cases that made up Brown v. Board of Education, ultimately leading to the 1954 Supreme Court decision that determined “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.”

Delaware public schools were forced to desegregate, with varying degrees of success. Schools in Wilmington became predominantly Black, while the surrounding suburban schools remained de facto white. Eventually, in 1978, Evans v. Buchanan — a case centered around Wilmington’s eleven school districts — mandated a plan for Black students in the city to be bused to white suburban schools, while white suburban students would be bused into the city.

Busing was opposed by whites who supported de facto segregation, and by some Black residents who saw it as changing the fabric of their communities and adding unnecessary logistical hurdles to their children’s education. In response to his constituents, Joe began voicing his opposition to busing in 1974, arguing in part that housing integration was a better area of focus to address inequality. Over the next four years, he put forward numerous proposals to limit federal and judicial authority on busing mandates.

“They wanted reading specialists in a lot of the schools,” Jill recalled. After a short time at Concord High School, she began working at Claymont High School as a reading specialist even though she would not finish her master’s degree until 1981. Ironically, Claymont had been the first school in the state to integrate, but the school board would later permanently close it in 1990 because of the school’s “racial imbalance.”

Through her role in the public school system, Jill saw firsthand the rapidly shifting situation. “They were desperate” for specialists, she said, to assist the new Black students who had come from underfunded schools and were behind in their reading skills.

Jill taught in the mornings, which let her keep many of the family’s life rhythms the same. She was still there to pick the boys up from school, waiting in the carpool line with the other parents each afternoon.

But Joe’s presence in the Senate kept her in the public eye. Although Jill registered for her graduate courses under Jacobs, her maiden name, people recognized her.

“The country didn’t know her,” Joe’s chief of staff, Ted Kaufman, later said, “but obviously every single person in Delaware knew her.”