James Shaw’s comments on Government climate 'action' draw a blunt response. David Williams reports.

Former Green MP Gareth Hughes left Parliament in 2020 and famously went to live on an island in Otago Harbour. He’s now moved back to the mainland (to Portobello, a harbourside village about 25 minutes from Dunedin’s central city) and has re-emerged publicly, criticising the Government’s record on climate change.

“There have been some welcome policies, like the clean car discount, but to date Government policy has not matched the scale of the climate emergency,” Hughes says via email.

“Time is running out for transformational policies that will deliver sustained reductions in New Zealand’s high levels of per-capita emissions.”

This isn’t some random exchange. Newsroom contacted Hughes, and other former Green MPs, about comments made by Climate Change Minister James Shaw.

The Green Party co-leader’s Beehive office issued a statement last month announcing the country’s updated inventory of greenhouse gas emissions. (For the record, gross emissions dropped 3 percent between 2019 and 2020, mainly because of Covid-19-related lockdowns.)

The statement said, “The actions this Government has taken have changed the trajectory of our emissions”, adding there’s “a lot to do” for the country to get on track to net-zero.

Newsroom asked Shaw’s office to provide a list of Government policies that have made a verifiable change.

The response was: “The most useful thing here to refer to is the cumulative impact of current policy settings - that is what Minister Shaw means when he talks about bringing down the trajectory (though, as he says, we haven’t done so nearly enough yet).

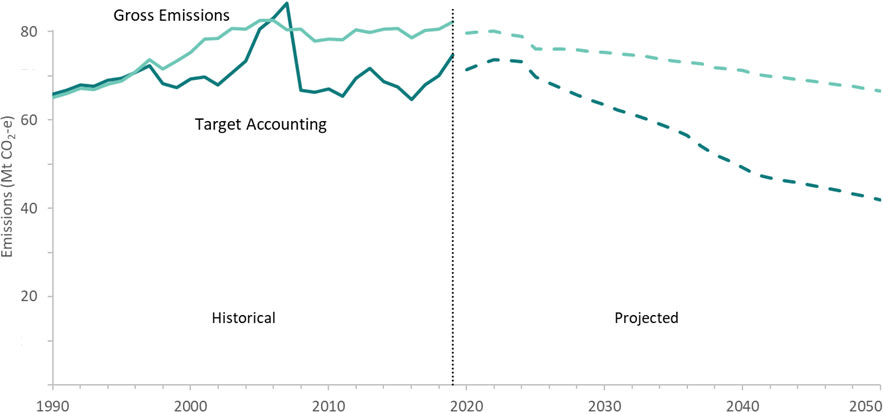

“You can see the cumulative effect of policies in recent Government projections, which show pretty clearly that, based on current policy settings, GHG emissions are expected to decrease.”

The “actions”, then, are “current policy settings” - that a future government might dismantle - altering “projections”. Some would say that’s indicative of the climate policy of New Zealand governments, of every stripe, over the past 30 years.

Hughes says: “It’s debatable that the trajectory has shifted and we’ll only know if that's true looking in the rear-view mirror but it’s clear right now New Zealand isn’t doing enough to reduce emissions.”

To underline how the trajectory has changed, Shaw’s office sent a link to a Ministry for the Environment webpage.

Historical and projected greenhouse gas emissions

The website projects emissions to 2050 will be 41.9 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent - 2.5 Mt CO2-e higher than last year’s projection. And the 2050 figure is not net-zero.

Dave Frame, a Professor of Climate Change at Victoria University of Wellington, says the Government has been too ambitious on targets, and too unambitious on actual mitigation - enlarging a credibility gap between promises and delivery. He doesn’t see any evidence of a change in trajectory yet, more year-to-year “noise”.

“Unless gross CO2 emissions drop, then you’ll need to keep buying offsets every year to mask the warming from the emissions you haven’t mitigated,” he says via email.

Frame’s colleague, Professor James Renwick, a climate scientist who also sits on the Climate Change Commission, says the Government has laid the groundwork for a transition. If its plan follows the commission’s advice, the country will be on track for zero-carbon.

“Having said the above, it’s my opinion that no government in the world, and no major business in the world, has taken climate change as seriously as it should,” he says in an email,

“We have collectively been gambling with our collective future, to make money in the short term. My hope is that New Zealand will very soon be a global leader in reducing greenhouse gas emissions and will help the world go in the direction we need.”

The picture might change next week, as the country’s emissions reduction plan is made public, ahead of details of climate-targeted spending in the Budget, and a flagged $4.5 billion climate emergency response fund.

Shaw claims more action has been taken on climate change over the last four years “than the combined efforts of governments over the last four decades”.

“There will always be more to do but we are in an historic period for climate action in New Zealand - and it simply would not have happened without the Greens in Government.”

With Shaw repeating the word “action”, it’s worth seeing if his former colleagues agree with his assessment. (Many didn’t in January.)

What is the Government’s climate record?

Russel Norman, a former Greens co-leader and climate change spokesperson, left Parliament in 2015 to take his current job as executive director of Greenpeace Aotearoa.

He lists this Government’s three top achievements as an oil and gas exploration ban, greater investment in KiwiRail, and a cap on synthetic nitrogen fertiliser - none of which will reduce emissions in the short-term.

Norman puts responsibility for those moves down to, in order: Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern and Energy Minister Megan Woods; New Zealand First; and Environment Minister David Parker. None, by his telling, because of the Greens.

As for the Zero Carbon Act, and the Climate Commission - “that’s just words”. “They’re easy to roll back.”

(Greenpeace is campaigning for synthetic nitrogen fertiliser to be phased out, and for the national dairy herd to be halved.)

Nándor Tánczos, a former environment spokesperson for the Greens, left Parliament in 2008. Now a Whakatāne councillor, by his own admission he hasn’t kept a close eye on the national scene of late. He remains a Green Party member.

He says the Government has shifted the public’s thinking on climate by setting clear targets for net-zero emissions by 2050, and there’s a greater focus on spending on public transport, cycling and walking infrastructure.

However, Tánczos says too much money is still going on roads. He also believes the Government isn’t prepared to take on the country’s biggest emitter - agriculture. (A voluntary scheme, He Waka Eke Noa, is being negotiated. Interestingly, in answer to question in Parliament on March 31, Shaw said he agreed with Agriculture Minister Damien O’Connor the national herd size doesn’t need to be reduced. In 2017, O’Connor told Newsroom the country was close to peak cow.)

“The Government’s done some useful things; I think James is trying to get some change. But the size of the response, compared to the enormity of the problem, is just completely lacking.”

That echoes the earlier point of Hughes, who confirms he’s no longer a Green Party member.

Hughes - whose biography on the late Jeanette Fitzsimons, a former Green Party co-leader, will hit bookstores later this month - says the emissions reduction plan needs to vastly increase in ambition and scale from the draft the public was consulted on.

“New Zealand can’t continue to rely on inadequate international targets, creative accounting and pine plantations to mask our long-standing lack of deep and decisive action,” he says.

“The ERP will be a crucial yardstick on how the Government's climate record will be judged.”

Climate action is long overdue. Since 1990, the country’s net emissions (taking into account carbon sinks, like forestry) have increased by 26 percent - mostly due to increased methane from dairy cattle and carbon dioxide from road transport.

Internationally, New Zealand is seen as a laggard.

Agricultural emissions continue to be subsidised by the public, Hughes laments. Also, there’s been a weakening of the offshore oil exploration policy, new coal mines proposed, huge coal imports, and significant infrastructure projects locking in increased emissions without climate impact reports.

“The ERP needs to fix these and other gaps in our climate response if we really want the trajectory to change.”

Tracking progress

It’s four-and-a-half years since Shaw told the United Nations climate change conference in Bonn, Germany, New Zealand intended to become a leader in the global fight against climate change.

The Zero Carbon Act passed in 2019, and the Climate Change Commission established. The commission gave its first advice to Parliament last year.

On Monday of this week, the country’s emissions budgets to 2035 were announced. Shaw says the emissions budgets are “a critical part of our strategy to rapidly cut the pollution that causes climate change”.

This coming Monday, he’ll announce the emissions reduction plan, the blueprint for reaching the first budget, to 2025. The first investments from the climate emergency response fund will also be revealed.

“For the first time ever, New Zealand will have a plan that requires nearly every part of Government to act to reduce emissions right across the country and to ensure all New Zealanders benefit from the transition.

“This is a very big deal.”

A lot is riding on these announcements. Not least, New Zealand’s contribution to the future of the planet in the face of more dire warnings from climate scientists, who say rapid and deep emission reductions are needed to avoid the catastrophic impacts of global warming.

Just yesterday, the World Meteorological Organisation said the world was close to exceeding, albeit briefly, the important 1.5°C threshold of post-industrial warming.

Although New Zealand is one of the few countries to enshrine in law net-zero emissions by 2050, its climate promises have been panned as inadequate, especially because of our high per-capita emissions.

Yes, our nationally determined contribution under the Paris climate agreement has been tightened, but much depends on offshore offsets.

This country has also been seen as obstructionist, by our diplomats helping to have references to “plant-based” diets scrubbed from an influential report by the IPCC, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Newsroom’s reporting has revealed Shaw pushed for a more ambitious Paris target. He also wanted agriculture to be included in the country’s net-zero commitments, but was vetoed by Cabinet.

Frame, the Victoria University professor, says having Shaw outside Cabinet is a problem when climate change depends on close coordination with so many other ministerial portfolios.

Are the Greens hamstrung?

Tánczos opposed the Greens signing a cooperation agreement with Labour in 2020, when the larger party had the numbers to rule alone. But he’s loathe to be too critical of Shaw, who he says is in a difficult position - “in a government that doesn’t need his vote”.

The party has previously made gains from opposition, such as the $323 million nationwide home insulation scheme. However, Tánczos says it’s difficult to compare something so visible, backed by a Beehive public relations machine, with often-invisible policy discussions within government. Law changes and policy frameworks can’t be done from opposition.

Tánczos isn’t sure the lack of climate action is hurting the Greens - support seems to be holding up in the polls.

“The Green Party remains the party that’s most committed to action on climate change, and the most committed to the environment, most committed to social justice.”

(Interestingly, on Monday, the political voice from within Parliament calling for stronger emissions budgets was Te Pāti Māori. Co-leader Debbie Ngarewa-Packer said: “We have no time delay, Papatūānuku is crying out for help.”)

Would less progress have been made without the Greens? “Probably,” Tánczos says. “But as I said before, it’s nothing like at the scale that we desperately need.”

So, who’s holding the Government to account?

Newsroom ran through oral questions in Parliament this year for climate-related queries on emissions, the clean car discount, renewable energy, and decarbonisation. Labour’s MPs have asked seven patsy questions, ACT asked three, and National one.

Only once, on March 15, did the Greens ask such a question. Ricardo Menéndez March asked the Transport Minister what steps he’ll take to ensure people have access to free, frequent, and accessible public transport.

Questions on methane

Methane emissions make up 44 percent of overall greenhouse gas emissions, and agriculture is half of gross emissions.

Farming leaders remain resistant to cutting them, however. Methane, emitted by ruminant animals like dairy cows and cattle, is about 84 times more powerful as carbon dioxide over 20 years, but doesn’t last as long in the air.

Federated Farmers’ national president Andrew Hoggard argues if methane emissions are stable they’re not adding warming to the atmosphere. This might be logical, but scientists say methane is responsible for up to half of the current temperature rise, and emissions should be reduced aggressively.

Surely, methane can be cut at the same time as carbon dioxide? “If you’ve got the mitigations, yes,” Hoggard says. “In New Zealand we don’t currently have the mitigation.”

Future cuts will depend on technology, research and development, he says. “That’s where the change is going to come from.”

New Zealand has spent more than $200 million since 2009 researching agricultural emissions. Shouldn’t those tools have already emerged?

Low-emission sheep breeding is coming online, Hoggard says, and trials continue on feed inhibitors, which are expected to be available within five years. “We’re nearly getting there.”

Would Federated Farmers oppose agriculture entering the emissions trading scheme? “The current ETS, yes we’d oppose that,” Hoggard says.

That’s a clean sweep of entrenched views to keep the status quo, calls for further research, and a reliance on future technologies.

Meanwhile, the Government pursues He Waka Eke Noa, the voluntary programme which, the dairy industry has boasted, has kept farmers out of the ETS. According to price modelling from last year, the scheme will achieve negligible emissions reductions.

In April, as the latest IPCC report was released, United Nations secretary-general António Guterres accused some governments and business leaders of “lying” about climate promises.

How does New Zealand stack up?

The Green Party’s list of the Government’s climate achievements include an emergency being declared, and the promise of a carbon-neutral public service by 2025. Coal boilers in schools, hospitals and universities are being replaced, and electric vehicles are being bought for the Government’s vehicle fleet.

Climate-related aid has been increased.

The emissions trading scheme has been overhauled, putting a sinking lid on emissions, and leading to a rapid increase in the carbon price. There’s also the billion trees scheme, more electric vehicle chargers, and a green investment fund.

Yet the biggest factor in emissions reductions in 2020 was Covid-19, and the Climate Change Minister acknowledges policies and frameworks have only changed the “trajectory” of future emissions.

Is this climate “action”?

Let’s rewind the clock to 2015, when the climate deal was agreed in Paris.

The New Zealand government of the time was accused of soft-peddling on climate. It was said to be out of step with other developed countries, with inadequate pollution-reduction targets, and a reliance on buying offshore credits rather than making cuts at home.

Countries were entering an action phase.

“We haven’t seen this shift yet in New Zealand,” said Green Party co-leader James Shaw. “If there’s ever a time to stop making excuses, it’s now.”