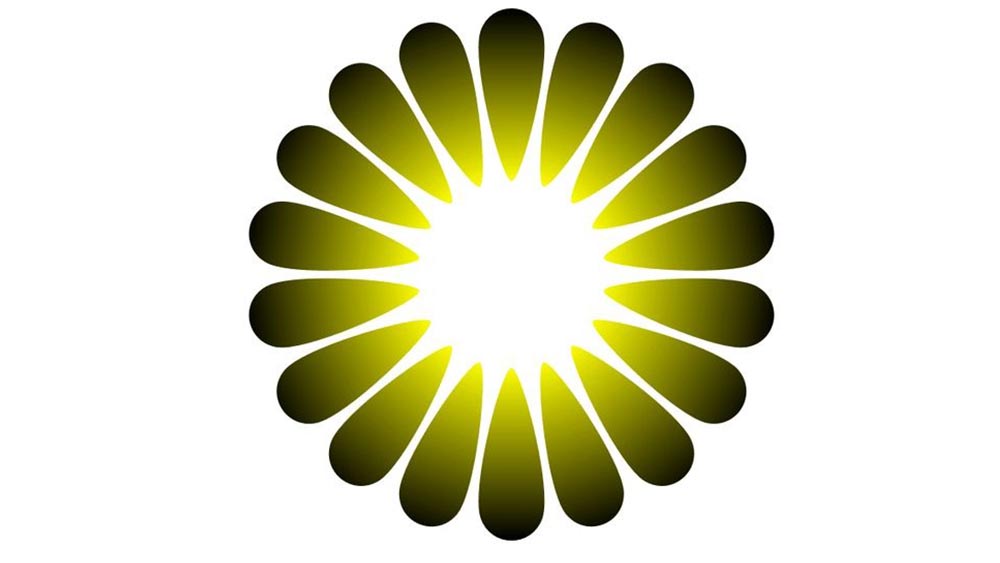

Love a good optical illusion? So do we – and so do rats, it turns out. The Asahi illusion is a particularly baffling one that tricks our perception of light. Looking a little like a flower, it features petal-like shapes around a white centre. The petals are black on the outer edges but transition to yellow as they taper, creating an effect which makes the white centre look brighter than it is.

Through a mechanism that isn't yet fully understood, the optical illusion causes our pupils to constrict in reaction to the perceived light. Scientists had thought this reaction was exclusive to humans, but no; it turns out that rats react in the same way, which means scientists may be able to study the response (now, I'm wondering how rats would react to all of our favourite optical illusions).

The Asahi optical illusion works because of the combination of the gradient colour and the shape of the petals. A 2012 study led by Dr. Bruno Laeng found that our brain is tricked into thinking that the centre has a brighter-than-white glare, triggering a pupillary light reflex through which our pupils narrow – an impulse designed to protect our eyes from overpowering light like that of the sun.

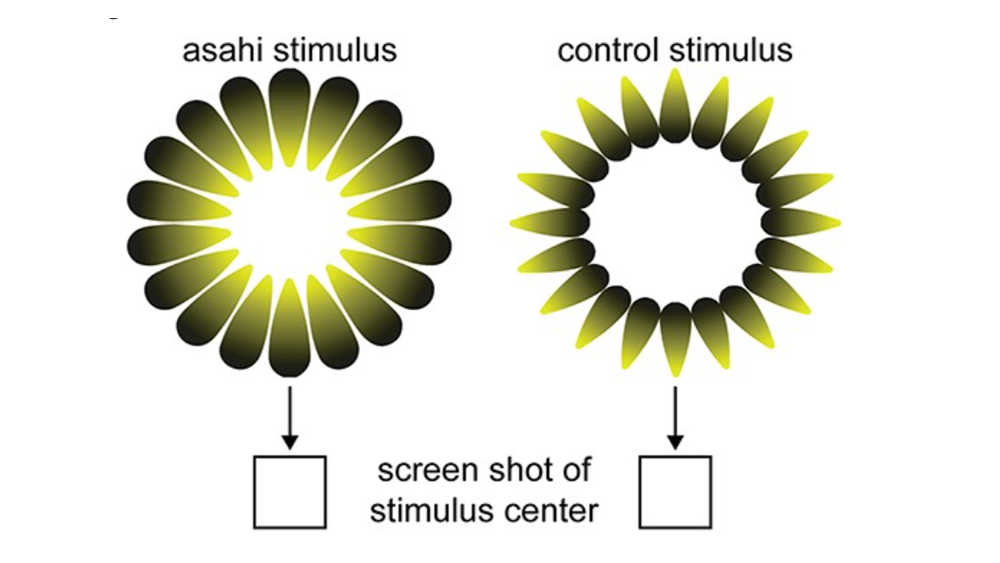

Now a new study, 'Brightness illusions evoke pupil constriction preceded by a primary visual cortex response in rats', has been published by Dmitrii Vasilev, Isabel Raposo and Nelson K Totah in Oxford University Press's Cerebral Cortex journal. The researchers showed illustrations of the Asahi stimulus and a luminance-matched control stimulus to rats and surveyed the response of most of rat cortex by recording cortex-wide EEG.

They tested the optical illusion on rats to learn more about the evolution of the eye in mammals, and the results suggest that the connection between perception and pupil size evolved earlier than scientists thought. That provides scientists with a means to investigate this example of “mind–body” connection. To date, the central nervous system network driving the pupil response to such illusions is unknown. Scientists needed an animal model to be able to investigate it, but it was thought that the response only occurred in humans.

We've already seen that otters can see optical illusions, so it's starting to turn out that we're not the only species whose perceptions can be tricked by visual stimuli. Want to see examples of animals in the optical illusion rather than watching it? See our pick of the best animal optical illusions.