Even mild cases of Covid-19 during pregnancy “exhaust” the placenta and damage its immune response, new research suggests.

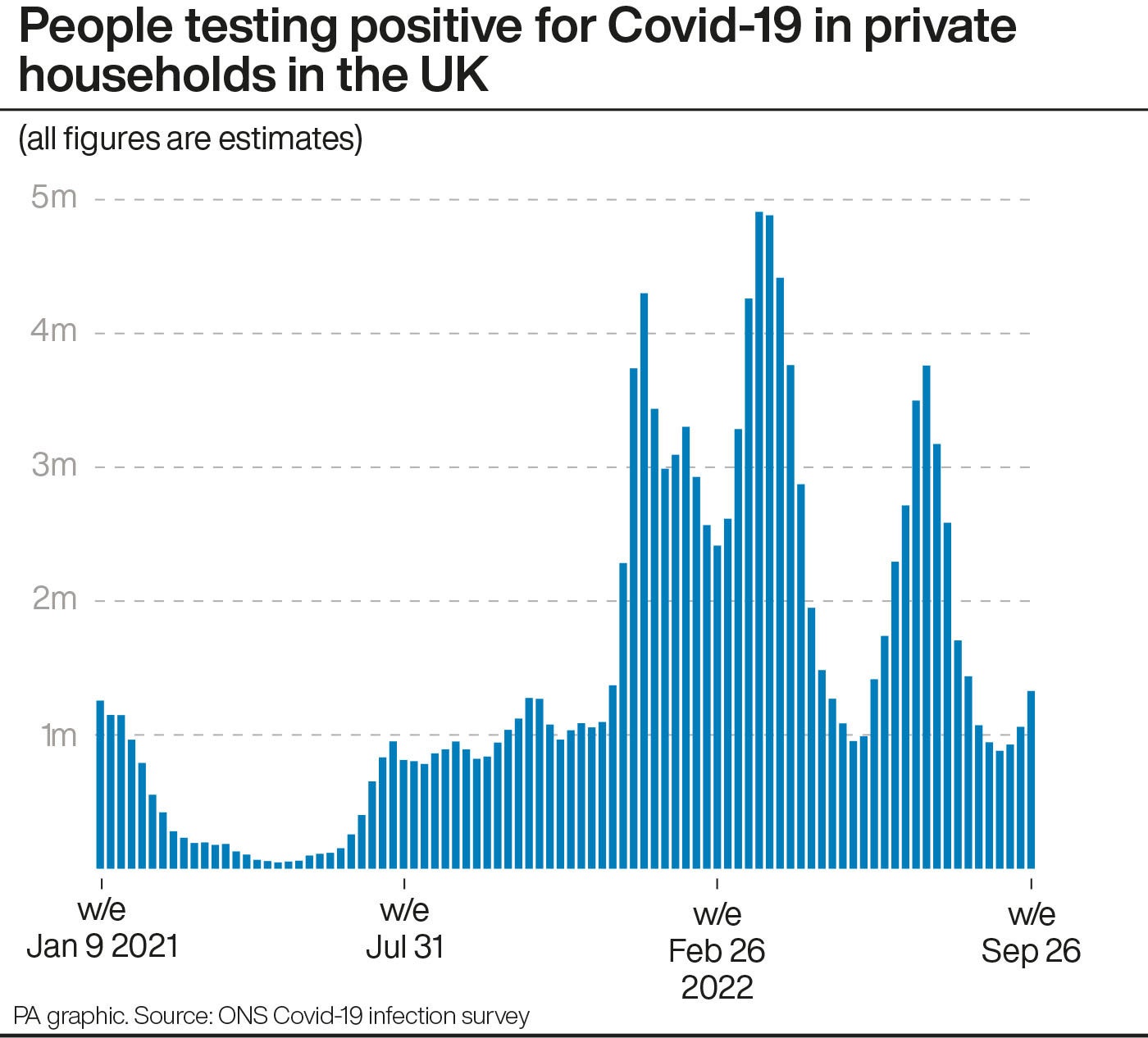

The findings, which come as coronavirus cases are again on the rise in the UK, lend weight to multiple studies over the course of the pandemic linking the virus to a rise in dangerous pregnancy complications such as pre-eclampsia.

But the results of the study – the largest yet involving the placentas of infected women – may represent the “the tip of the iceberg” of how Covid-19 affects foetal or placental development, warned Dr Kristina Adams Waldorf, the senior author on the study, which was published last month in the American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Early in the pandemic, it was widely assumed that the coronavirus did not harm the developing foetus because so few babies were born with the infection, said Dr Adams Waldorf, a professor of obstetrics and gynaecology at the University of Washington School of Medicine.

“But what we’re seeing now is that the placenta is vulnerable to Covid-19, and the infection changes the way the placenta works, and that in turn is likely to impact the development of the foetus,” explained the professor.

The study involved a total of 164 expectant mothers – 24 of whom were uninfected and acted as a control group, and 140 of whom contracted the coronavirus, of whom roughly 75 per cent were asymptomatic or had mild symptoms.

“The disease may be mild, or it may be severe, but we’re still seeing these abnormal effects on the placenta,” Dr Adams Waldorf said, referring to the organ that effectively acts as an unborn child’s gut, kidneys, liver and lungs while providing them with nourishment, oxygen and immune protection.

“It seems that after contracting Covid-19 in pregnancy, the placenta is exhausted by the infection, and can’t recover its immune function.”

While most infected pregnant women do not experience complications, the coronavirus does appear to heighten the risk of a number of severe conditions, such as pre-eclampsia, which a review of numerous studies has suggested is around 60 per cent more likely to occur in those with the virus.

Pregnant women who develop Covid-19 have also been found to be at increased risk of other complications, such as premature birth and infection.

The impact also appears to differ between variants. During the dominance of the Delta variant, smaller reports of a rise in stillbirths were eventually backed up by a national study involving some 1.2 million births.

One pathologist at the Cleveland Clinic described becoming “pretty panicked” by a sudden wave of stillbirths in unvaccinated mothers who developed Covid in the fortnight prior to giving birth, in which the placenta – typically soft and coloured dark with blood flow – was instead found to be firm, scarred, and a pale shade of brown.

“The degree of devastation was unique,” Amy Heerema McKenney told the The Washington Post, describing the placentas she examined in her laboratory that belonged to mothers who had lost their babies as looking like nothing she had ever seen before.

Some time later, in September 2021, a study by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention concluded that “although stillbirth was a rare outcome overall, a Covid diagnosis documented during the delivery hospitalisation was associated with an increased risk for stillbirth in the United States, with a stronger association during the period of Delta variant predominance”.

The link between such cases, however, appeared to diminish rapidly with the arrival of the Omicron variant, and other studies have failed to find a link between Covid and stillbirth.

“Studying each of the variants in real time is really challenging,” said Dr Adams Waldorf. “Because they just keep coming so fast, we can’t keep up. We do know that the Covid-19 Delta variant was worse for pregnant individuals, because there was a spike in stillbirths, maternal deaths and hospitalisations at that time.”

The study suggests that further research should be carried out to monitor babies born to mothers who have contracted the coronavirus during pregnancy, noting that early evidence suggests that such exposure could be associated with a higher rate of neurodevelopmental diagnoses.

“We predict that at least seven years of follow-up of a large population will be needed to determine differences in rates of autism spectrum disorder, and 25-30 years of follow-up to evaluate differences in rates of psychosis and schizophrenia,” the study stated.

Dr Adams Waldorf advised that women who are pregnant should first get vaccinated and boosted, and if possible continue to wear masks and stay within a bubble of individuals who are also vaccinated and boosted.