The Block has begun its 19th season this month, billed as “a Block that’s entirely relatable to people right around Australia”. This year, contestants renovate five “authentic ’50s dream homes” in “the perfectly named Charming Street, in Melbourne’s Hampton East”.

But if the median price for a four-bedroom house in Hampton East is around A$1.6 million and the nation’s housing crisis shows no signs of easing, who is The Block relatable to? And why do audiences keep coming back to renovation stories?

Home ownership is becoming less accessible and more people than ever are renting, but stories about renovation on TV, in film and in literature continue to have a powerful effect on us. Why?

One reason they can be so captivating is that they invoke the idea of the dream home.

Read more: Building costs have soared. Is it time to abandon my home renovation plans?

Home makeovers are ultimately about us too

Ask anyone you know about their dream home – something I did regularly when I was writing my PhD on renovation stories – and you’ll get an incredible array of different styles, sizes, locations. Maybe it overlooks the ocean, maybe it has the newest appliances, maybe it has a pool, maybe it’s just a house without a mould problem.

The idea of the dream home is deeply rooted in our shared imagination. The philosopher Gaston Bachelard wrote in The Poetics of Space (1958) that our houses – both the ones we live in and the ones we dream of – “move in both directions: they are in us as much as we are in them”. Bachelard suggests that in even “the humblest dwelling” our memories, desires and dreams are gathered, and this is why houses are so central to who we are.

If houses can be expressions of self, our dream houses say a lot about our desires. While it might no longer look like a house on a quarter-acre block, the dream still exists. Renovation stories are so compelling because in them, as researchers have noted, home improvement often represents self-improvement – a dream life, not just a dream house.

This is especially important in programs like Extreme Makeover: Home Edition (2003–20) and Backyard Blitz (2000–), which often focus on people presented as hard-done-by whose lives are changed by renovations that solve their day-to-day problems.

Read more: Future home havens: Australians likely to use more energy to stay in and save money

Better house, better life

Reality TV isn’t the only place we find this type of story about transformation and self-improvement. In Frances Mayes’ bestselling memoir Under the Tuscan Sun (1996), Mayes travels to Italy and buys an abandoned villa, Bramasole, which she renovates. In the process, she gains a new outlook on life.

There’s a similar story in Peter Mayle’s A Year in Provence (1989). Mayle, a UK advertising executive, buys a 200-year-old farmhouse in France and renovates it.

Both books were exceptionally successful, inspiring an entire genre of renovation memoirs about wealthy middle-class people able to travel abroad, buy charmingly rundown properties in beautiful locations, and renovate them while enjoying the local lifestyle. In them, renovation is a clear symbol of self-transformation, if only for people rich enough to afford it: renovating houses leads to a greater appreciation of life’s pleasures and a new way of seeing the world.

Read more: It seemed like a good idea in lockdown, but is moving to the country right for you?

This idea of the renovated life can be especially compelling in a world that increasingly feels frightening and overwhelming. Researchers like Fiona Allon argue that renovation stories allow us to turn away from the alarming outside world – with its violence, looming recessions, pandemics, climate crises – and focus on the smaller, more controllable world of the home.

Maggie Smith’s viral poem Good Bones (2016) plays with this idea. The poem is about a mother trying to convince her children (and herself) that despite being a scary place, the world can be improved. To do this, she uses the analogy of a real estate agent selling a fixer-upper. The poem ends with lines that present renovation as an opportunity for change:

This place could be beautiful,

Right? You could make this place beautiful.

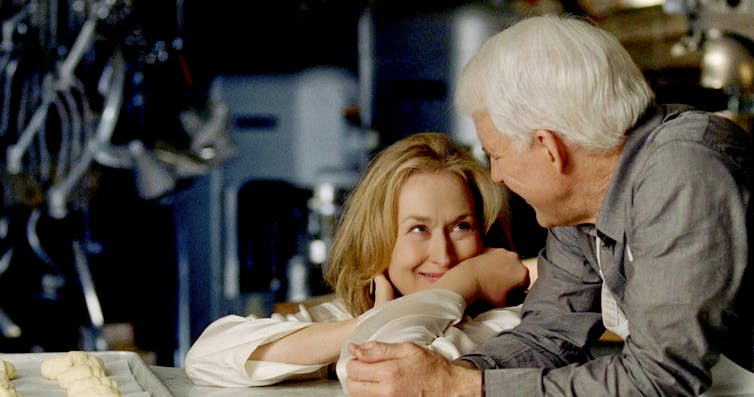

This optimism is what makes renovation excellent fodder for love stories. In the Nancy Meyers rom-com It’s Complicated (2009), Meryl Streep plays a divorcee looking for a fresh start, who renovates her home and falls in love with her architect, Adam. In The Notebook (2004), Ryan Gosling’s Noah transforms an old plantation estate into his lover Allie’s dream home, a gesture that reveals his enduring love.

Renovation stories are always about change (although in some the change doesn’t last). Even if, as may be the case for the increasing number of people who are renting, having a house of our own is itself a fantasy.

Read more: Off the plan: shelter, the future and the problems in between

Renovate? In this economy?

Many renovation stories can be seen as escapist media that trade on the image of the dream home to sell ideas about wealth, taste and style to audiences unable to afford such things. The Block may involve contestants from a range of backgrounds, but few people can afford the multimillion-dollar houses they build.

The Block’s viewership has had ups and downs in its two-decade history, but the show (and many others) continues because, despite being about profiting from the housing market, it sells the idea of transformation and change, not just in our houses but in our lives.

Renovation stories invite audiences to indulge in a fantasy where we become our best selves living in dream homes that protect us from a volatile and threatening world. The dream home might remain a dream, but in renovation stories we escape reality and envision life in a Tuscan villa, or having a butler’s pantry or plunge pool, or simply owning a house of our own.

Ella Jeffery does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.