The criminal referral of Donald Trump to the Department of Justice by a House committee investigating the Jan. 6 attack is largely symbolic – the panel itself has no power to prosecute any individual.

Nonetheless, the recommendation that Trump be investigated for four potential crimes – obstructing an official proceeding; conspiracy to defraud the United States; conspiracy to make a false statement; and inciting, assisting or aiding or comforting an insurrection – raises the prospect of an indictment, or even a conviction, of the former president.

It also poses serious ethical questions, given that Trump has already announced a 2024 run for the presidency, especially in regards to the referral over his alleged inciting or assisting an insurrection. Indeed, a Department of Justice investigation over Trump’s activities during the insurrection is already under way.

But would an indictment – or even a felony conviction – prevent a presidential candidate from running or serving in office?

The short answer is no. Here’s why:

The U.S. Constitution specifies in clear language the qualifications required to hold the office of the presidency. In Section 1, Clause 5 of Article II, it states: “No Person except a natural born Citizen, or a Citizen of the United States, at the time of the Adoption of this Constitution, shall be eligible to the Office of President; neither shall any Person be eligible to that Office who shall not have attained to the Age of thirty five Years, and been fourteen Years a Resident within the United States.”

These three requirements – natural-born citizenship, age and residency – are the only specifications set forth in the United States’ founding document.

Congress has ‘no power to alter’

Furthermore, the Supreme Court has made clear that constitutionally prescribed qualifications to hold federal office may not be altered or supplemented by either the U.S. Congress or any of the states.

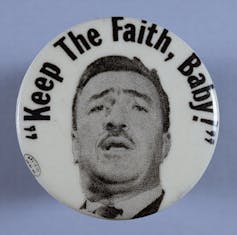

Justices clarified the court’s position in their 1969 Powell v. McCormack ruling. The case followed the adoption of a resolution by the House of Representatives barring pastor and New York politician Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. from taking his seat in the 90th Congress.

The resolution was not based on Powell’s failure to meet the age, citizenship and residency requirements for House members set forth in the Constitution. Rather, the House found that Powell had diverted congressional funds and made false reports about certain currency transactions.

When Powell sued to take his seat, the Supreme Court invalidated the House’s resolution on grounds that it added to the constitutionally specified qualifications for Powell to hold office. In the majority opinion, the court held that: “Congress has no power to alter the qualifications in the text of the Constitution.”

For the same reason, no limitation could now be placed on Trump’s candidacy. Nor could he be barred from taking office if he were to be indicted or even convicted.

But in case of insurrection …

The Constitution includes no qualification regarding those conditions – with one significant exception. Section 3 of the 14th Amendment disqualifies any person from holding federal office “who, having previously taken an oath … to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof.”

The reason why this matters is the Department of Justice is currently investigating Trump for his activities related to the Jan. 6 insurrection at the Capitol. And one of the four criminal referrals made by the Jan. 6 House committee was over Trump’s alleged role in inciting, assisting or aiding and comforting an insurrection.

Under the provisions of the 14th Amendment, Congress is authorized to pass laws to enforce its provisions. And in February 2021, one Democratic Congressman proposed House Bill 1405, providing for a “cause of action to remove and bar from holding office certain individuals who engage in insurrection or rebellion against the United States.”

Even in the event of Trump being found to have participated “in insurrection or rebellion,” he might conceivably argue that he is exempt from Section 3 for a number of reasons. The 14th Amendment does not specifically refer to the presidency and it is not “self-executing” – that is, it needs subsequent legislation to enforce it. Trump could also point to the fact that Congress enacted an Amnesty Act in 1872 that lifted the ban on office holding for officials from many former Confederate states.

He might also argue that his activities on and before Jan. 6 did not constitute an “insurrection” as it is understood by the wording of the amendment. There are few judicial precedents that interpret Section 3, and as such its application in modern times remains unclear. So even if House Bill 1405 were adopted, it is not clear whether it would be enough to disqualify Trump from serving as president again.

Running from behind bars

Even in the case of conviction and incarceration, a presidential candidate would not be prevented from continuing their campaign – even if, as a felon, they might not be able to vote for themselves.

History is dotted with instances of candidates for federal office running – and even being elected – while in prison. As early as 1798 – some 79 years before the 14th Amendment – House member Matthew Lyon was elected to Congress from a prison cell, where he was serving a sentence for sedition for speaking out against the Federalist Adams administration.

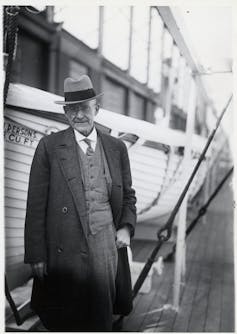

Eugene Debs, founder of the Socialist Party of America, ran for president in 1920 while serving a prison sentence for sedition. Although he lost the election, he nevertheless won 913,693 votes. Debs promised to pardon himself if he were elected.

And controversial politician and conspiracy theorist Lyndon Larouche also ran for president from a jail cell in 1992.

A prison cell as the Oval Office?

Several provisions within the Constitution offer alternatives that could be used to disqualify a president under indictment or in prison.

The 25th Amendment allows the vice president and a majority of the cabinet to suspend the president from office if they conclude that the president is incapable of fulfilling his duties.

The amendment states that the removal process may be invoked “if the President is unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office.”

It was proposed and ratified to address what would happen should a president be incapacitated due to health issues. But the language is broad and some legal scholars believe it could be invoked if someone is deemed incapacitated or incapable for other reasons, such as incarceration.

To be sure, a president behind bars could challenge the conclusion that he or she was incapable from discharging the duties simply because they were in prison.

But ultimately the amendment leaves any such dispute to Congress to decide, and it may suspend the President from office by a two-thirds vote.

Indeed, it is not clear that a president could not effectively execute the duties of office from prison, since the Constitution imposes no requirements that the executive appear in any specific location. The jail cell could, theoretically, serve as the new Oval Office. Of course, managing a presidency from a prison cell would in itself raise myriad issues in regards the handling of sensitive or classified documents.

Finally, if Trump were convicted and yet prevail in his quest for the presidency in 2024, Congress might choose to impeach him and remove him from office. Article II, Section 4 of the Constitution allows impeachment for “treason, bribery, and high crimes and misdemeanors.”

Whether that language would apply to Trump for indictments or convictions arising from his previous term or business dealings outside of office would be a question for Congress to decide. The precise meaning of “high crimes and misdemeanors” is unclear, and the courts are unlikely to second-guess the House in bringing an impeachment proceeding. For sure, impeachment would remain an option – but it might be an unlikely one if Republicans maintained their majority in the House in 2024 and 2026.

Editor’s note: This is an updated version of an article originally published on Nov. 16, 2022.

Stefanie Lindquist does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.