High-tech DNA analysis of skeletons buried 8,000 years ago in France reveals that the last hunter-gatherer groups in Europe likely developed cultural strategies to avoid inbreeding, a new study suggests.

An investigation into the genomes of 10 people who lived between 6350 and 4810 B.C. revealed few biological links among these small communities, according to a study published Feb. 26 in the journal PNAS.

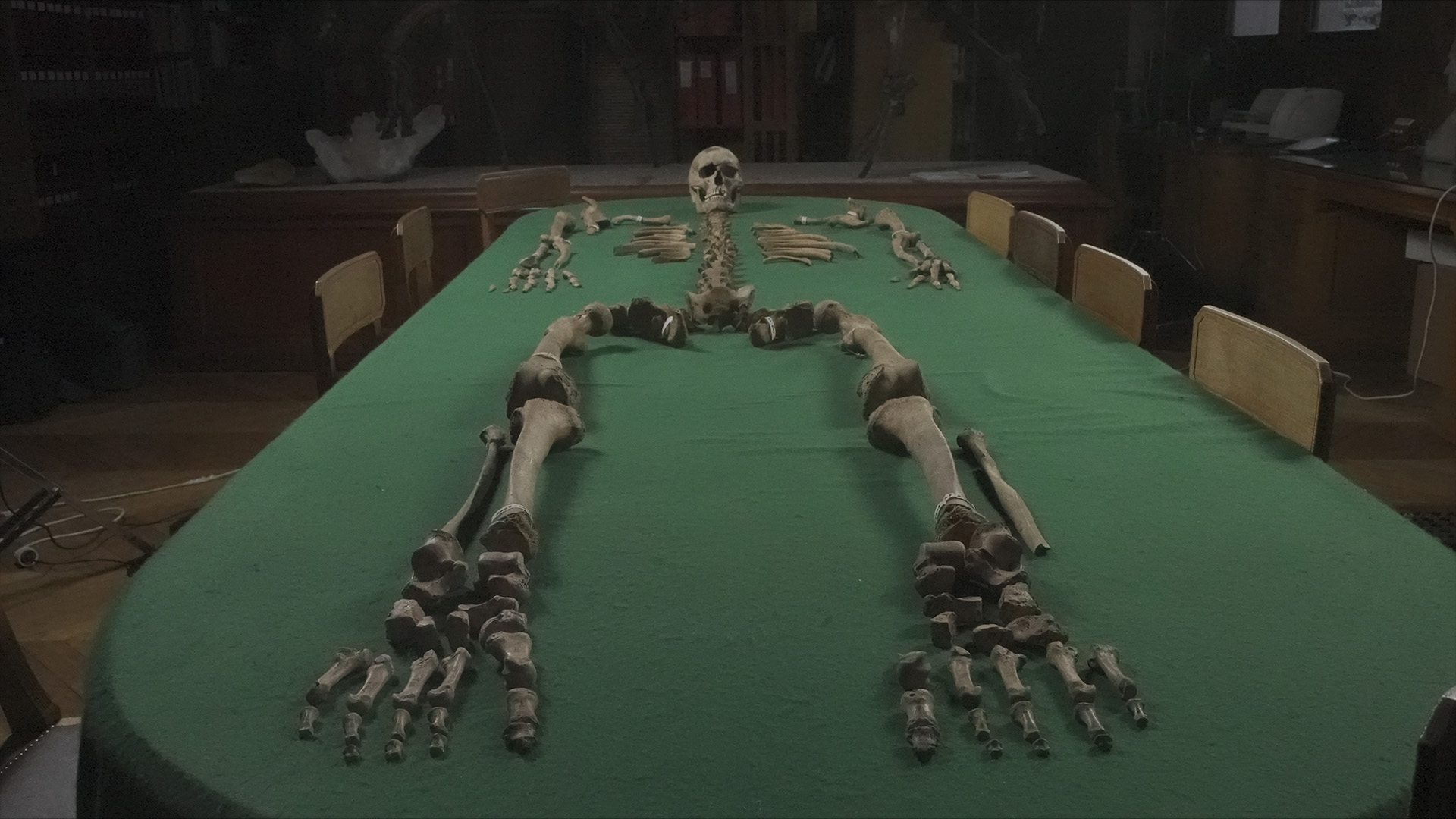

Most of the individuals the researchers tested were buried at Téviec and Hoedic (also spelled Hœdic), two coastal archaeological sites in northwestern France that are notable for two reasons: They contain a large number of well-preserved human skeletons, and they date to the period when Western Europe was transitioning from foraging to farming.

Related: Largest-ever genetic family tree reconstructed for Neolithic people in France using ancient DNA

In the Brittany region of France, the "Neolithic transition" occurred around 4900 B.C., resulting in major changes to settlement patterns, technology, diet and burial practices. Hunter-gatherer groups were largely replaced by farming communities, with some previous genetic evidence showing that members of hunter-gatherer groups left their communities and mated with farmers. But the question of whether genes flowed the other way — from farmers to foragers — had not previously been answered.

Looking at the genomes of people buried at Téviec and Hoedic, the research team discovered that all of the individuals were genetically similar to other Western European hunter-gatherer groups, with no evidence that they mixed with the first farming groups, which existed contemporaneously in northwestern France.

Even though these prehistoric hunter-gatherer groups had a small number of people and did not mate with larger farming groups, "contrary to expectation, individuals buried together did not have close biological kin relationships," the researchers wrote in their study. In fact, most of the biologically related pairs they found had third-degree — such as cousin, half-uncle, great-grandparent — relationships.

"We know that there were distinct social units — with different dietary habits — and a pattern of groups emerges that was probably part of a strategy to avoid inbreeding," study lead researcher Luciana Simões, a geneticist and postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Organismal Biology at Uppsala University in Sweden, said in a statement.

Christina Bergey, an assistant professor of genetics at Rutgers University in New Jersey who was not involved in the study, told Live Science in an email that the work is "super exciting" because the genomes the team sequenced shed light on human culture at the pivotal point of the Neolithic transition.

"Many people often erroneously equate hunting-and-gathering with simplicity or even primitiveness," Bergey said, but avoiding inbreeding requires societal sophistication. "Perhaps complex social boundaries and identities persisted, even as most of our species moved toward agricultural societies," she said.

One aspect of the complexity of hunter-gatherer social relationships can be seen in a grave at the site of Hoedic, which included the skeletal remains of a female adult and a young girl, who, to the researchers' surprise, were not genetically related.

"This suggests that there were strong social bonds that had nothing to do with biological kinship and that these relationships remained important even after death," study co-author Amélie Vialet, a lecturer at France's National Museum of Natural History, said in the statement.