This is part five of this feature: Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 6

As the closing notes of God Save The Queen hung in the north London sky on a baking hot June 23 afternoon, Stuart Pearce turned to Gareth Southgate, beaming with pride.

Seldom had the England pair experienced an atmosphere anything like this – particularly Southgate, a well-mannered young lad from the Home Counties who was still a little green when it came to the raucousness created in England’s summer of football love.

Tens of thousands of supporters went mad, a wall of noise swelling to deafening decibels. Pints of piss then began to rain down from the well-lubricated crowd. “And another one, please!” came the raspy voice of Johnny Rotten across the PA system. “Who wants a good shag?”

Some 24 hours before the Sex Pistols were introduced to the Finsbury Park stage by Southgate and punk-loving Pearce, the duo lined up for the traditional version of 1977’s visceral takedown of the establishment, ahead of a quarter-final tie against Spain.

The atmosphere inside Wembley was no less intense than that at Finsbury Park, albeit with fewer excreted projectiles or Johnny Rotten’s awkward attempts to get laid. Whipped into a frenzy by England’s stunning 4-1 win over the Dutch, the tabloid press had decided now was the time to invoke a bit of old-fashioned xenophobia on proceedings.

“You’re done, Juan,” read the Daily Mirror’s front page, alongside a picture of a Beefeater preparing to behead a matador.

When it was reported the day before the match that the Spanish FA had returned 5,000 unsold tickets, the papers wasted no time piling in. “It’s the biggest retreat since Sir Francis Drake sent the Spanish Armada packing in 1588,” crowed The Sun, rarely backwards about coming forwards when it comes to remembering a shellacking of Johnny Foreigner.

“Not only are there mad cows in England,” winked Spain’s daily sports paper El Mundo Deportivo, “the English press is also infected.” Up to now, Spain had been shielded from the London bubble for their three group games against Bulgaria, France and Romania, which were all played in Leeds.

“I loved every minute of Euro 96,” defender Abelardo tells FFT. “There was this… feeling, different to anything I’d experienced at other tournaments, like something was happening. I’d dreamt of being part of something like that since I was a kid.”

Spain were 19 games unbeaten – they last lost in the quarter-finals of USA 94, to Italy – and they were the one team Venables didn’t want to face. The England manager talked up Italy, Germany and the Netherlands in these very pages in May 1996, but he finished with: “They’ve all got good players and knowhow… but I think Spain are stronger.”

Opposite number Javier Clemente – a sort of Basque Brian Clough – was feeling confident. “Zubizarreta, Alkorta, Sergi, Hierro, Caminero,” he responded to FFT’s question about who the players of the tournament could be. “What do they all have in common?”

Spain had made a meal of getting through their group, however, drawing with Bulgaria and France before needing a Guillermo Amor goal six minutes from time to beat Romania. Now they were facing the hosts, who were on a high after a big win against the Netherlands.

“You know what you’re going to face,” says Abelardo. “You are going into the lions’ den – a team that’s up for it, tactically well drilled, with a full crowd at Wembley, a stadium which is a big deal for any foreign team.

“The atmosphere that day was spectacular. It definitely felt like fulfilling a lifelong ambition, playing in such an important match against a host country. If you can’t enjoy a game like that, then you never will.

“We knew all about ‘Football’s coming home’. It was a very good song, and you’d almost find yourself humming it to yourself, too!”

England’s solitary change was, as expected, David Platt for the suspended Paul Ince.

“I was so gutted to miss the Spain match,” recalls Ince. “We always said the Spanish were the team, so to get them – I feared that could be my tournament over.”

Abelardo would find himself in the very same position for a possible semi-final, booked for going through the back of Alan Shearer inside the opening minute. “He was difficult to mark because he constantly changed positions with Sheringham,” says the Spaniard. “After that, we had to change who we were picking up.”

Yet the Three Lions struggled for any rhythm against La Roja’s narrow back three. Shearer forced a fine save from Andoni Zubizarreta and later skied a volley at full stretch, while Tony Adams – without an international goal since 1988 – had a header tipped easily over the bar. But aside from a few balls into the box which nearly found their target, that was the extent of England’s opportunities across 120 minutes.

Twice Spain had the ball in the net, courtesy of Kiko and Julio Salinas, but twice the French linesman raised his flag. Replays immediately showed that Salinas’ goal should have stood. “Who’s to argue with the linesman?” the BBC’s Trevor Brooking asked of Barry Davies, tongue pressed firmly in cheek.

“Where was VAR when you need it?!” says Abelardo, laughing. “We had clearer chances, but it was very equal. When you have a lot of things against you – the crowd and the feeling around the whole country – you know if you don’t take your chances, you might regret it.”

Regret it they would, after a nerve-jangling extra time in which the hosts were a handful of last-ditch tackles away from letting in the Golden Goal which would have eliminated them at a stroke from their own tournament.

Six years on from Italia 90, English football’s bête noire was back: a penalty shootout. Surely Spain, freed of the psychological trauma that had engulfed English football since Turin, were the favourites here?

“Did I know about England’s record? Er, no – had they always won them?” Abelardo asks FFT two and a half decades later. “We had no idea penalties were such a thing for England.”

Each team’s regular takers walked up first. Shearer scored, but Fernando Hierro rattled the bar. Advantage England. Platt and Amor kept their nerve... before Wembley fell silent, onlookers unable to believe their eyes.

“A brave man steps forward to take England’s third,” said Davies. Stuart Pearce, who missed in 1990, put the ball on the spot. The crowd’s collective heart rate rose. “Terry Venables asked for some volunteers, so I put my hand up,” Pearce told FFT in 2014. “He looked shocked and said, ‘Are you f**king sure?’ Yes, I was. I was a good penalty-taker. Failure wouldn’t have been to miss again – it would have been not to try.”

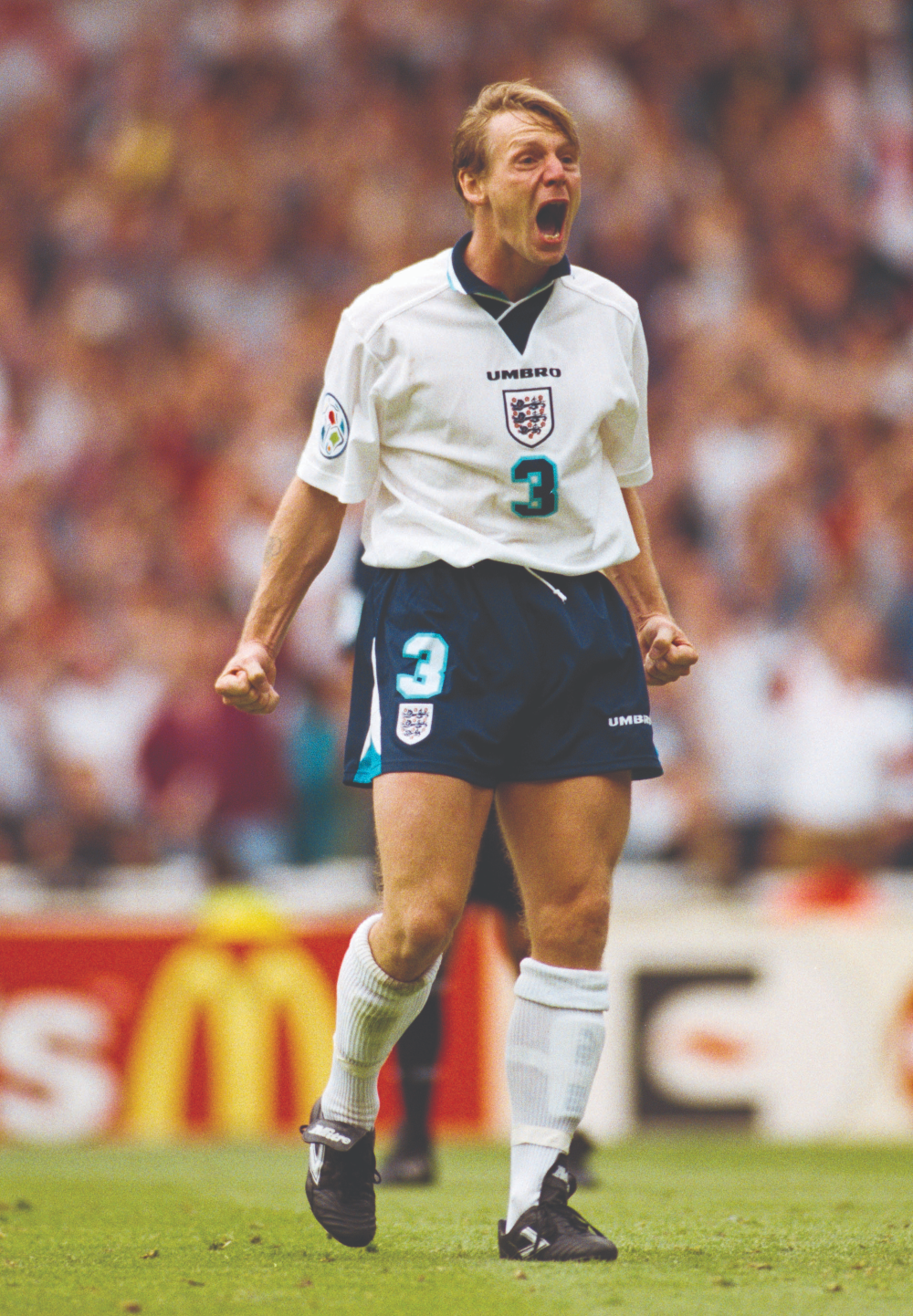

The man they called Psycho pummelled his penalty into the bottom-right corner, and his fist-pumping, eyes-bulging, throat-shredding explosion of catharsis became an iconic event beyond football.

On this day at Euro 96, Stuart Pearce's redemption as @England beat Spain on penalties to reach the tournament's semi-finals #ENG #ThreeLions pic.twitter.com/Acq2UiiFXbJune 22, 2018

“The emotion completely consumed me,” said Pearce. “Even now, decades later, it’s the one picture I’m asked to sign the most. Show that image to any football fan and they will know what game it was and what happened.”

After Alberto Belsue and Paul Gascoigne had exchanged successful penalties, Miguel Angel Nadal stepped forward. David Seaman dived left and parried his shot away. The Three Lions were, somewhat fortuitously, into the last four.

“You’ve got to say well done to Spain,” said Tony Adams. “They showed why they’ve gone so many games without losing.”

Flashback, Euro 96, David Seaman saves from Spain's Nadal to send England into the semi-finals #Euro2016 #England pic.twitter.com/JBCHiM8WRbJune 7, 2016

“It was our best performance of the entire tournament,” Abelardo tells FFT. “I remember feeling such jealousy watching England in the semi-final, thinking, ‘That should be us’.”

Interestingly, no one in Spain – not even the press – made anything of Hierro and Nadal missing penalties. Neither have been asked about it since. It happened; move on and win in 90 minutes next time.

“Miguel Angel has a very big character and, to be honest, we were all just consoling each other because we’d gone out,” says Abelardo. “You only miss because you’ve got the balls to stand up and take a penalty. There was no way I would ever be taking one – I was rubbish at them. I don’t think I took one as a professional – so who’s really the bad guy?”

Answer: the officials, at least in the opinion of centre-forward Julio Salinas, still smarting from his wrongly disallowed goal. “You can’t play against 11 players, 80,000 fans and three referees,” he huffed.

England, meanwhile, was unsurprisingly ecstatic. A country that was already at fever pitch had now turned up the dial way beyond a Spinal Tap 11.

“Spain still can’t beat an English Seaman,” cheered the Daily Telegraph, determined not to miss out on yet another Armada pun. Sex Pistols gigs provided an unlikely afterparty for a nation losing its giddy mind.

There’s no future in England’s dreaming? At least they now had a chance to find out.

This feature first appeared in the February 2020 issue of FourFourTwo - get the latest issue now.

This is part five of this feature: Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 6