Amid skyrocketing poverty and inflation, Argentinians face a stark choice on Sunday between two wildly different presidential candidates. Libertarian Javier Milei has led a disruptive campaign that has galvanised voters and won support from a faction of the traditional far-right. But a shock first-round victory for current Economy Minister Sergio Massa has set the scene for a down-to-the wire race in the final round of voting on Sunday.

As the results for the first round of voting were announced on October 22, cheers and hugs broke out in the campaign headquarters for government minister Massa.

Two months earlier Massa – who has overseen triple-digit inflation in Argentina – had achieved a mediocre result in the open primaries, which determined the first-round candidates. The economy minister brought in 27.3 percent of the vote, placing him third behind the leader of the far-right coalition Patricia Bullrich (28 percent) and first-round victor, political outsider and self-proclaimed "anarcho-capitalist" Milei (30 percent).

But, weeks later, the tables had turned dramatically. Massa, representing Union for the Homeland (UP), defied the polls and stormed to a spectacular first-round victory with 36 percent of the vote, pushing Milei into second place with 29.9 percent, and third-place Bullrich out of the race.

The return of Peronism

Political magazine Nueva Sociedad said the 51-year-old’s victory was a form of protest against his main opponent, writing “in the face of Javier Milei's chaotic utopia, support for Massa ended up being a sort of defensive vote by a section of society”.

While Milei’s campaign was characterised by fiery outbursts and stunts such as wielding a chainsaw onstage, “Massa emerged as 'the adult in the room'”, it said, “position[ing] himself as the only politician capable of managing the Argentine state. In short, he donned the suit that suits him best: that of a pragmatic politician".

With an unexpected leap from 27.3 percent of the vote to 36 percent in just two months, Massa seems to have succeeded in convincing Argentinians worn out with incessant inflation that a Milei victory would mean a dangerous leap into the unknown both economically and democratically.

Positioning himself as the first line of defence against an opponent who wants to ditch the peso for the US dollar, privatise health and schooling and make it easier to buy guns and human organs has been no easy feat for Massa.

As the current economy minister, he is a figurehead for the unpopular outgoing administration, which has left Argentina in dire financial straits with poverty rates soaring and inflation jumping 143 percent.

Crushing the right

Massa’s victory has also thrown Argentina’s political right into chaos.

Three days after being eliminated in the first-round vote, Bullrich, from center-right coalition Together for Change (JC), threw her support behind outsider Milei, urged on by former centre-right president Mauricio Macri.

"Javier Milei and I had our differences, that’s why we ran against each other,” she told the press. “However, we are faced with a dilemma: change or continue with mafia-style governance in Argentina. We must put an end to … the domination of corrupt populism which has led Argentina towards total decadence [of the Peronist government]. We have an obligation to not remain neutral.”

In doing so, Bullrich, who formerly held the post of security minister, also re-endorsed one of the pillars of her own campaign: the “eradication” of Peronism, an Argentine political ideology embodied by the current government, including deeply unpopular vice-president and Massa supporter Christina Fernandez de Kirchner.

That evening, former rivals Bullrich and Milei shared a warm exchange on a television programme, while social media showed images of Milei as a lion holding Bullrich, depicted as a goose, in his clutches.

But other figures on the political right refused to follow Bullrich in endorsing Milei and accused ex-president Macri of having played into the far-right populist’s hands throughout the campaign.

Gerardo Morales, president of the Radical Civic Union (UCR) party, a longstanding part of the coalition on the right, called Milei a “puppet”, “emotionally unbalanced” and “a very dangerous figure for Argentine democracy”.

The implosion of the political right and the spectacular rise of Massa has redrawn the political landscape in Argentina and left its political class facing difficult questions.

Milei has denounced the right as a “parasitic political caste” – if it’s politicians were now to endorse the outsider candidate, would it help or harm his campaign?

“The problem of support is that it contributes to the dislocation, or at least the toning down, of Milei’s anti-system rhetoric,” said Gaspard Estrada, executive director of Sciences Po’s Political Observatory of Latin America and the Caribbean (OPALC).

“Before the first round, Milei criticised the political class," he said. "The fact that, from one day to the next, he made an alliance with an establishment figure will dilute the strength of his message.”

But at the same time, there is “a real desire for change and to turn the tables” among Argentine voters, said FRANCE 24’s correspondent on the ground Mathilde Guillaume.

“Most poor workers that we have been speaking to in working-class neighbourhoods want to see change and Javier Milei has managed to channel that desire," she said. "Support from Mauricio Macri, who is a favourite among the establishment, gives [Milei] a sheen of respectability and increases his chances of being elected.”

Controversy vs national pride?

Even so, the desire for change at any cost that many in Argentina are feeling often clashes with Milei’s radical ideology.

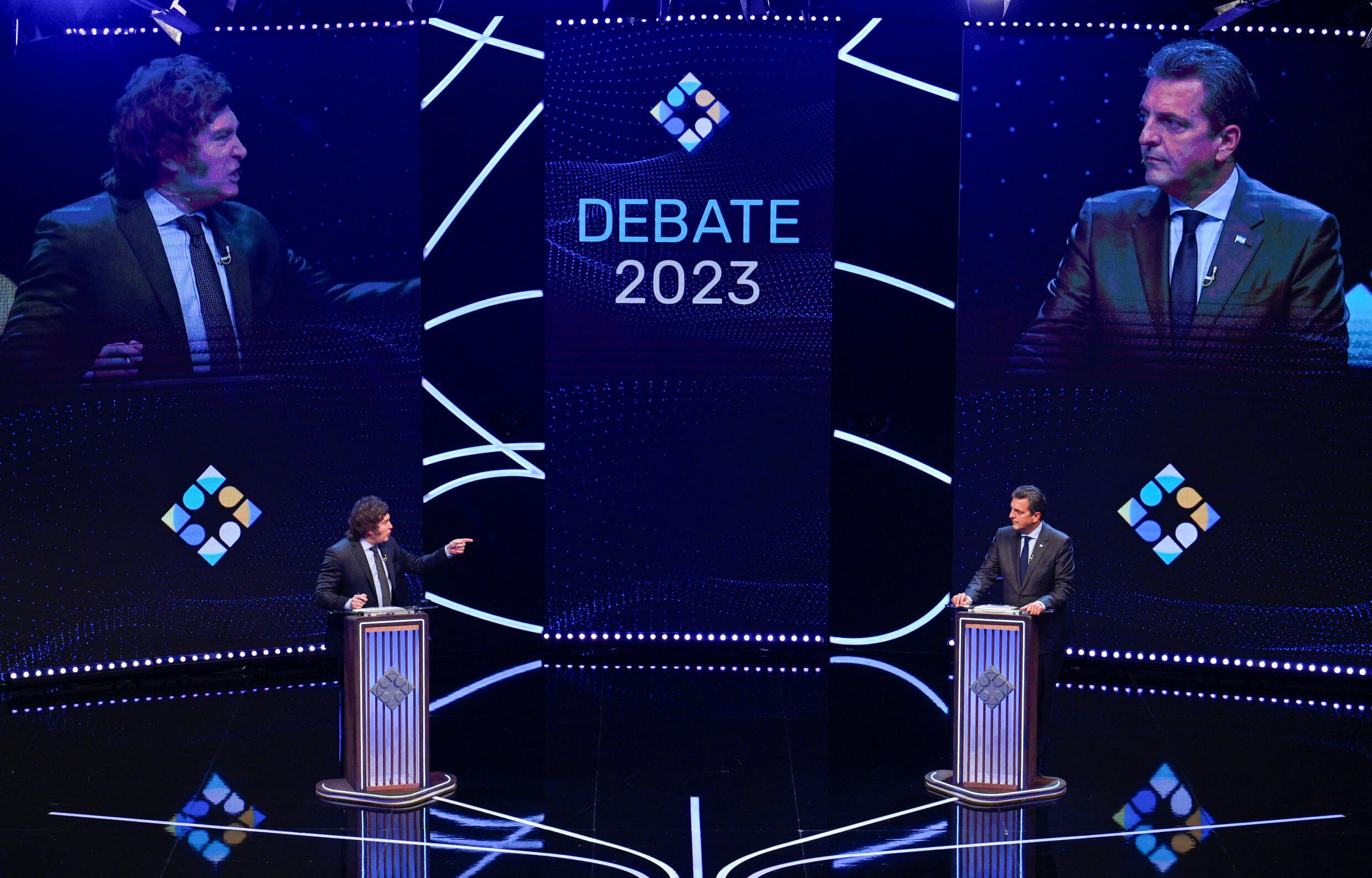

During a debate held between two rounds of voting the provocative candidate had warm words for an old Argentine adversary, ex-Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, who led Britain during the Falklands War.

Thatcher was “a great leader in the history of humanity,” Milei said.

Directly to Massa he added, “Thatcher had a significant role in the fall of the Berlin Wall and it seems that its fall and the crushing of the left bothers you. That’s your problem.”

“Yesterday, today and forever, Thatcher is an enemy of Argentina,” came Massa’s stinging response, reaffirming Argentine sovereignty of the Falklands, which Argentina claims as Islas Malvinas, and honouring the memory of the soldiers who lost their lives in the 1982 conflict.

Falklands war veterans have strongly criticised Milei’s proposals to open negotiations with the British government to bring the chain of South Atlantic islands back under Argentine jurisdiction.

Massa has also played on another source of national pride during his campaign, saying that he would be in favour of a visit to Argentina by Pope Francis, who was born in Buenos Aires.

In doing so Massa has made a direct appeal for the Catholic vote and further differentiated himself from Milei, who shocked some supporters when he said the Catholic leader was “representative of the evil one on Earth” and an "imbecile who defends social justice".

If taking a provocative stance on Thatcher and the Pope may have harmed Milei’s standing with voters, his running mate, Victoria Villaruel, has done little to calm their fears.

As Argentina celebrates 40 years of democracy this year, Villaruel has been a staunch defender of military personnel convicted of active participation in the the country’s military dictatorship from 1976-1982.

Villaruel, a colonel’s daughter, is a long-term advocate of the “two demons theory”, which blames both the revolutionary left and the military dictatorship for political violence committed in the 1970s.

During a debate between the two vice-presidential candidates, Villaruel contested the widely accepted estimate that 30,000 people were disappeared by the military during the dictatorship as “a lie” propagated by the left.

The 2005 annulment of Argentina’s amnesty laws, which had previously blocked the prosecutions of crimes committed under the country’s military dictatorship, has never been called into question.

Read moreMy father, the war criminal: Children of Argentina's dictatorship grapple with dark past

Villaruel’s adversary Agustín Rossi accused her of trying to destabilise Argentinian politics by “breaking the democratic pact that all political forces had concluded”.

But imprisoned military personnel convicted of crimes against humanity have expressed public support for the Milei-Villaruel ticket.

Change or continuity?

On Sunday, Argentina will make its choice between a libertarian provocateur with outlandish solutions to its economic crisis or a member of the political establishment who symbolises painful economic realities.

So far, opinion polls show Massa and Milei are neck-and-neck in a presidential race that is too close to call.

Awareness that Milei is using tactics similar to successful populists such as former US President Donald Trump and former Brazilian leader Jair Bolsonaro is no guarantee that Arentina “will avoid an extreme right government,” said Argentine historian Ezequiel Adamovsky.

It is extreme economic distress – for which Massa as minister for the economy holds responsibility – that has pushed Argentina to embrace Milei as an outsider candidate.

And it is Milei who has created a seemingly formidable opponent out of an unpopular establishment figure.

“Sergio Massa has not found himself in this position [of winning the first round] because of his own merits as a candidate, and even less so because of the merits of the government, but because of the enemy he faces,” said Adamovsky. “It takes two to tango, as the old proverb goes.”

This article has been adapted from the original in French.