The brand-new spacecraft Euclid has beamed back its first commissioning images from space, thus bringing scientists closer to understanding dark matter and dark energy.

The news might feel like a paradox. Telescopes cannot see the dark universe because it doesn’t interact with the electromagnetic spectrum. Euclid has a solution: go big. The fresh images are a critical step for the European Space Agency (ESA) mission to take the largest 3D map of the universe to date, and use that grand view to pinpoint how dark matter and dark energy engage with the brilliant objects vibrantly decorating our celestial canvas.

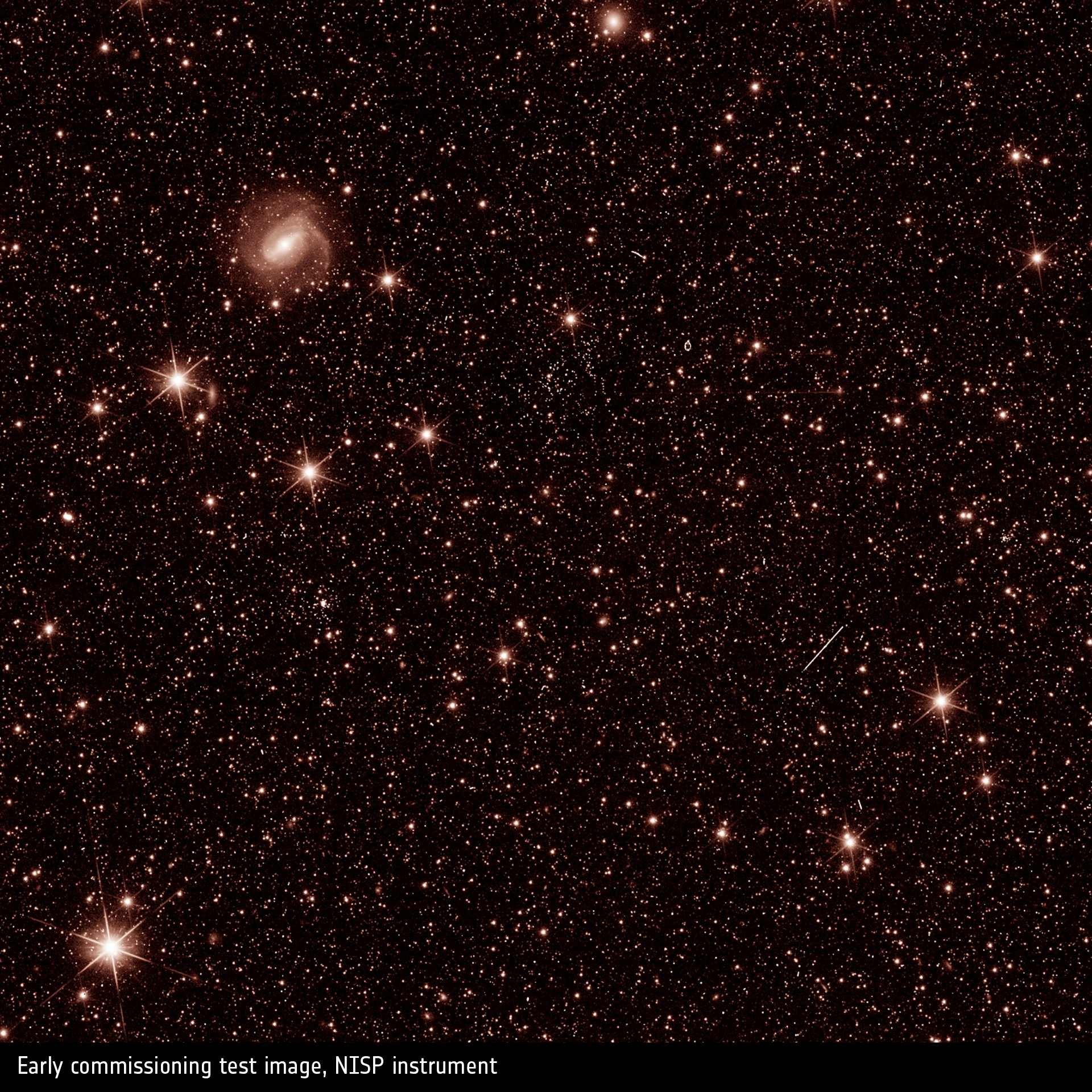

“We’ve seen simulated images, we’ve seen laboratory test images — it’s still hard for me to grasp these images are now the real Universe. So detailed, just amazing,” Euclid scientist Knud Jahnke shares in a mission update ESA published on Monday.

What appears in Euclid’s images?

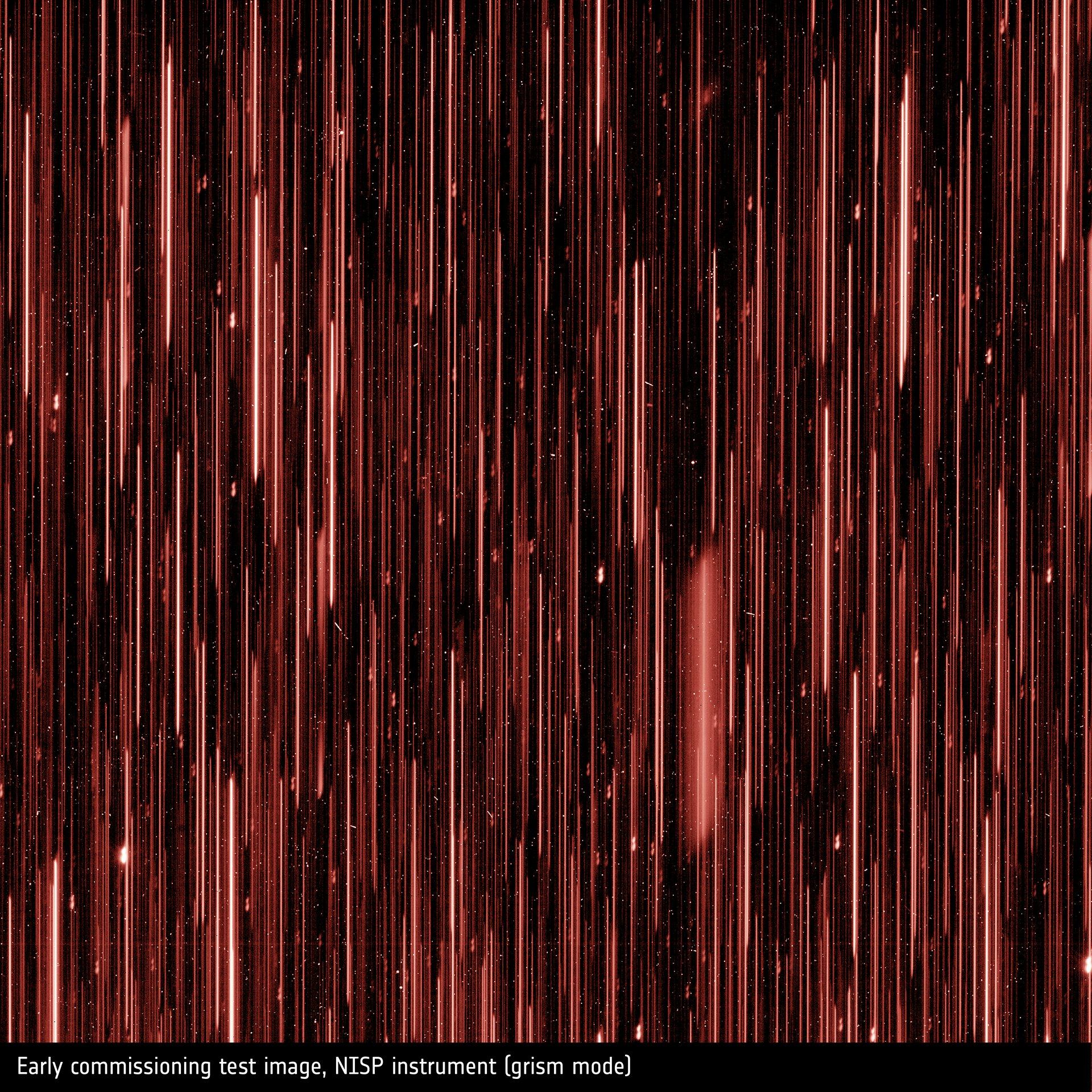

Pinpricks glitter across the background of the Euclid commissioning images from objects in the distant universe. And then closer to Euclid’s science suite, made up of the Visible Instrument (VIS) and the Near-Infrared Spectrometer and Photometer (NISP), there are galaxies with clear elliptical and spiral shapes. Stars and stellar clusters also make an appearance.

The longest exposures lasted less than five minutes to acquire these sights, according to ESA. The clarity and speed at which Euclid gathered these views is a good sign: to map one-third of the extragalactic night sky in six years, images must be time-efficient and pristine.

These raw views also show blemishes that won’t appear in future science images. For instance, cosmic rays have left streaks. ESA says the Euclid Consortium of scientists will clean them up in official data.

How does Euclid reveal the dark universe?

Euclid’s two instruments each have different roles.

Euclid’s NISP instrument, which gathers light in multiple wavelengths, tells scientists about object distances. And since light travels at a finite speed, farther distances are farther back in time. This services the exploration of dark energy, the mysterious outward force that drives the accelerated expansion of the universe.

VIS, which shows the shapes of galaxies in great detail, can support the study of dark energy as it illuminates changes in form across grand time scales.

VIS can also support investigations into dark matter, the elusive substance thought to bind galaxies and their clusters together. Because dark matter doesn’t interact with light, but has mass, one trick astronomers have developed to find it is to look for gravitational lensing. In this cosmic extreme scenario, mass is so concentrated that it distorts and bends visible light.

“Each new image we uncover leaves me utterly amazed,” Euclid scientist William Gillard shares in the ESA statement. “And I admit that I enjoy listening to the expressions of awe from others in the room when they look at this data.”