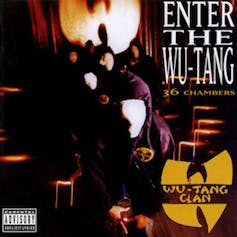

2023 marks the 50th anniversary of hip-hop culture and the 30th anniversary of the Wu-Tang Clan’s Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers).

Released on Nov. 9, 1993, the 36 Chambers introduced its audiences to the world of the Wu-Tang Clan which was largely inspired by Asian martial arts and films.

Scholars working on Afro-Asian encounters, hip-hop and the transnational circulation of film have discussed the connection between martial arts and hip-hop culture at large.

My research examines how in the making of hip-hop culture, kung fu films were mythic models by which urban youth ritually transformed their world into that of the urban warrior. It is not that these youth became literal “warriors,” but that they reimagined their hip-hop performance arts as martial arts.

The Wu-Tang Clan’s 36 Chambers repeated these same rituals and paid homage to mythical and martial origins of hip-hop culture.

In the beginning

Hip-hop traditionally goes back to the summer of 1973. It was a New York City subculture of urban youth that emerged alongside a pop-cultural craze for Asian martial arts and films.

Discussing martial arts and hip-hop culture, some scholars focus on the cross-cultural impact of Bruce Lee, who historian Robin D.G. Kelley describes as an Asian American “among a pantheon of Black heroes.”

Cultural critic Nelson George goes so far as to credit 1970s kung fu movies for helping create hip-hop culture, because well into the early 1980s, hip-hop pioneers like Grandmaster Flash and Furious Five were inspired by kung fu films.

George’s 2016 Netflix series, The Get Down, dramatizes hip-hop’s origins in the Bronx, New York. In this drama, Grandmaster Flash mentors Shaolin Fantastic, whose belt-buckle reads “kung fu” with an image of Bruce Lee.

Why this martial arts and hip-hop connection?

Of course, hip-hop artists customarily competed with rival artists. Marcyliena Morgan, a social sciences professor who writes on hip-hop language and culture, speaks of an inherent battle ethos that made hip-hop translatable as martial arts.

Historian Fanon Che Wilkins explains that films like Wu-Tang’s beloved 36th Chamber of Shaolin (1978) were full of East Asian religious imagery and symbolism, notably that of Taoism, Zen Buddhism and Confucianism. And imagining oneself as a martial artist could elevate one’s competitive play to a spiritual practice.

Issues of race and gender were also at stake. Martial arts provided young Black American men with dignified ideals of manhood that opposed racist stereotypes of black masculinity.

But while Asian martial arts and films were rich with esthetic, spiritual and racial significance, in all cases, they inspired Black and brown youth to reimagine their artistic lifestyles as warrior-like. Asian martial arts and films functioned like mythic models for the making of urban warriors, and later the Wu-Tang Clan.

Enter the 36 Chambers

36 Chambers debuted in 1993, when hip-hop music was commercially dominated by West Coast gangster rap. This genre, says George, drew its inspiration from the 1970s Blaxploitation films that also informed hip-hop culture.

Like some gangster rap, 36 Chambers dealt with the lived realities of urban youth. Songs like “Tearz,” “Can It All Be So Simple,” and “C.R.E.A.M.” talked about the inner-city conditions that cause untimely deaths, poverty and criminality.

But unlike Snoop Doggy Dogg’s November 1993 debut, Doggystyle, which enveloped listeners in a “Doggy Dogg World” of gangsters, pimps and hustlers, 36 Chambers drew from the esthetics of Chinese kung fu films and immersed audiences in a world of lyrical warriors.

MCing as martial art

On this album, the art of MCing was first and foremost a martial art. One could be annihilated in the “36 chambers of death” by “360 degrees of perfected styles.”

In the spirit of battling, songs like “Protect Ya Neck,” “Wu-Tang Clan Ain’t Nuthing Ta F* Wit,” and “Bring Da Ruckus” conveyed the danger and deadliness of the Wu’s lyricism. The latter song opened with a movie sample that presented the Wu as serious threat to all would-be MCs.

The sample was taken from Shaolin and Wu-Tang (1983), a film after which the Wu had crafted their identity as a group of nine men from the slums of Shaolin. Shaolin is a historical Buddhist tradition in China, but here it symbolizes Staten Island, New York, where the Wu-Tang Clan as a group was formed.

Spiritual meaning of 36

While the aforementioned songs and sample were meant to induce a feeling of being in a martial world, the 36 Chambers was also based on the 36th Chamber of Shaolin, a film that showed how martial arts was both a physical and spiritual ordeal. Thus, there was more to entering the 36 Chambers than chopping off MCs’ heads and warning them to “protect ya neck!”

The number “36,” for instance, had a spiritual meaning. For the Wu, this meaning was based on several numerological correlations between the number 36, the nine members of the band, and the number of chambers in each member’s heart.

It was also based on the teachings of the Five Percent Nation (also called Nation of Gods and Earths), a Black American movement influenced by Islamic traditions in which the Wu and other rappers were engrossed.

Suffice it to say that to “enter the 36 chambers” was to enter the myth and mysteries of the Wu-Tang Clan. This was also implied by the album’s esoteric cover art and song, “Da Mystery of Chessboxin’,” which likewise took its name from a kung fu film.

Overall, the album extended an initiatory call to experience, what sociologist Tricia Rose terms the emotional and sonic force of Wu’s music. It was a sonic rite of passage into their martial styles and spirituality.

Re-enter hip-hop

On the 25th anniversary of the album, the former Shaolin monk and Wu-Tang affiliate, Shi Yan Ming, said the only way to enter hip-hop is by entering the Wu-Tang Clan’s 36 Chambers. His statement presupposes that we accept authentic MCing as a martial art.

Whether we agree with Shi Yan Ming or not, 36 Chambers recalls hip-hop’s mythical and martial influences. This is one way in which it belongs in conversations about hip-hop’s 50th year anniversary.

Wu-Tang Forever!

Marcus Evans does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.