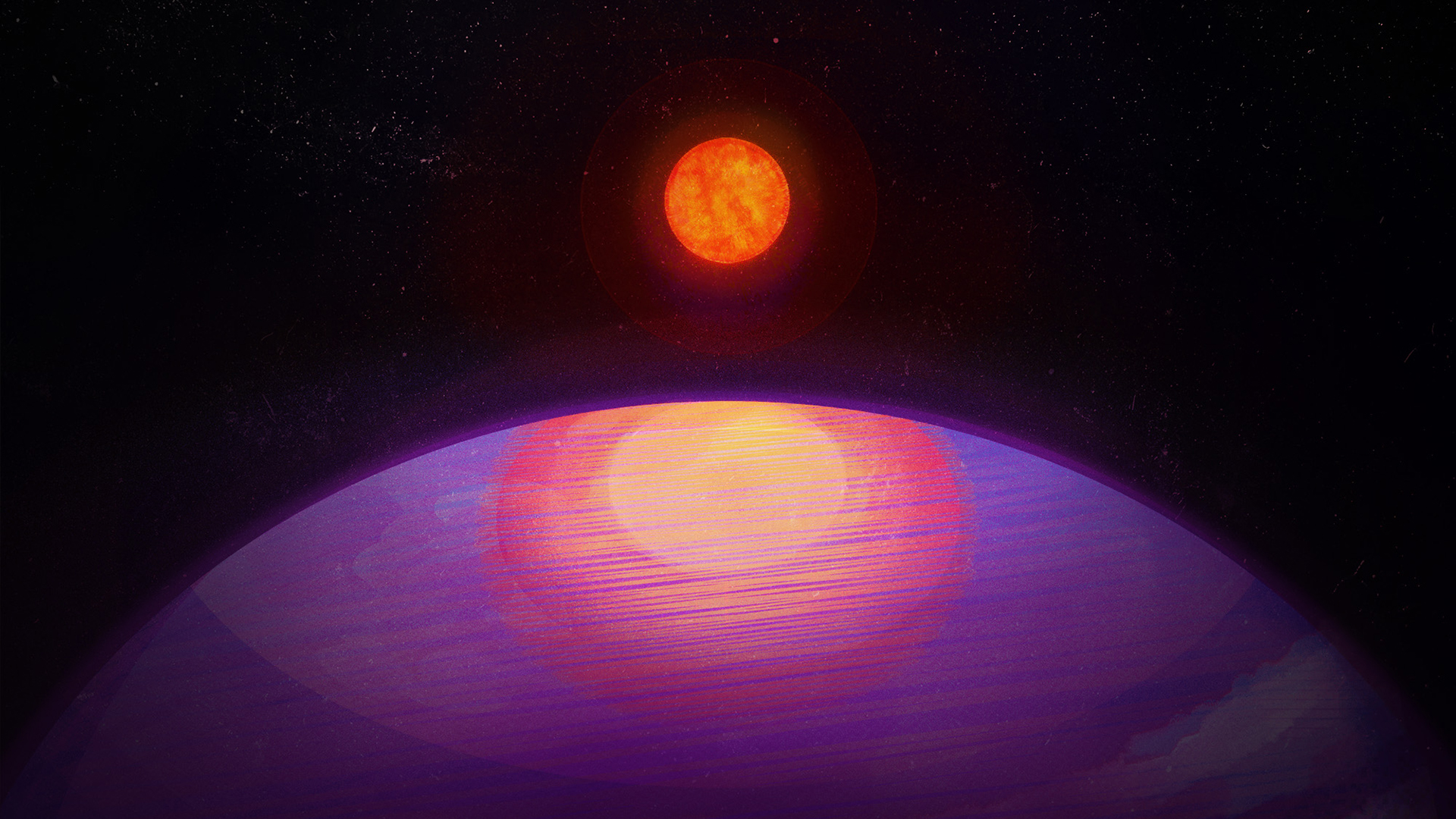

Scientists have discovered a planet that is way too big for its tiny star. Its existence could upend everything we thought we knew about how solar systems form, researchers say.

The ultra-cool dwarf star, named LHS 3154, lies 51 light-years from our solar system and is about nine times less massive than our sun. In contrast, its planet, LHS 3154b, is 13 times more massive than Earth. That sort of cosmic mismatch is previously unheard of — the astronomical equivalent of finding a watermelon on a grapevine.

"We wouldn't expect a planet this heavy around such a low-mass star to exist," study co-author Suvrath Mahadevan, an astronomer at Penn State , said in a statement.

Mahadevan and his team found the system using an instrument known as the Habitable Zone Planet Finder (HPF) at the McDonald Observatory in Texas. HPF is designed to detect (relatively) cool stars like LHS 3154, as the planets orbiting them are more likely to have water on their surfaces. However, the researchers weren't expecting to find an oversized planet orbiting one.

While LHS 3154b is far from the most massive exoplanet discovered so far (that honor likely goes to the gas giant HAT-P-67 b, which has a radius about twice that of Jupiter), its size relative to its star is record-breaking, and the discovery challenges the current scientific understanding of how planetary systems form. When a new star emerges from a cloud of cosmic dust, the rest of the material in that cloud becomes a disk around the baby sun. This disk of dust, gas and pebbles then begins to condense into increasingly large balls of rock, which eventually snowball into planets.

But LHS 3154b is so large that researchers think it would require about 10 times the amount of dust that's estimated to have been present around its newly formed star. Based on this discrepancy, it seems likely that such systems are extremely rare. The researchers hope that further analysis will reveal just how the planet got so big — and why its star is so small in comparison.

"This discovery really drives home the point of just how little we know about the universe," Mahadevan said.

The scientists published their findings Nov. 30 in the journal Science.