England’s housing sector accounts for 20% of the country’s emissions. Its stock is outdated and efforts to improve the energy efficiency of England’s homes are limited.

The country also has a housing crisis. Successive governments have responded to this by building more homes. The current government wants 300,000 extra homes built each year, coupled with adding energy-efficiency measures to existing homes.

But our research demonstrates that, based on current trends, England’s housing strategy could consume our entire carbon budget by 2050. This is England‘s share of the global emissions required to limit global heating to 1.5℃ by 2050, as agreed as part of the Paris Agreement. The majority would be consumed by the emissions of existing stock, with the remainder mainly arising from the construction of new homes.

Meeting society’s housing needs without causing lasting damage to the environment is a challenge. Retrofitting existing homes, providing social housing, reducing second-home ownership and disincentivising the purchase of homes as a financial investment are all possible solutions.

Addressing housing emissions

Around 54% of England’s homes are so energy inefficient that the Climate Change Committee – the UK’s independent advisor on climate change – recommends they must be retrofitted by 2028 to achieve national climate targets. Addressing the emissions of the existing stock is an important step.

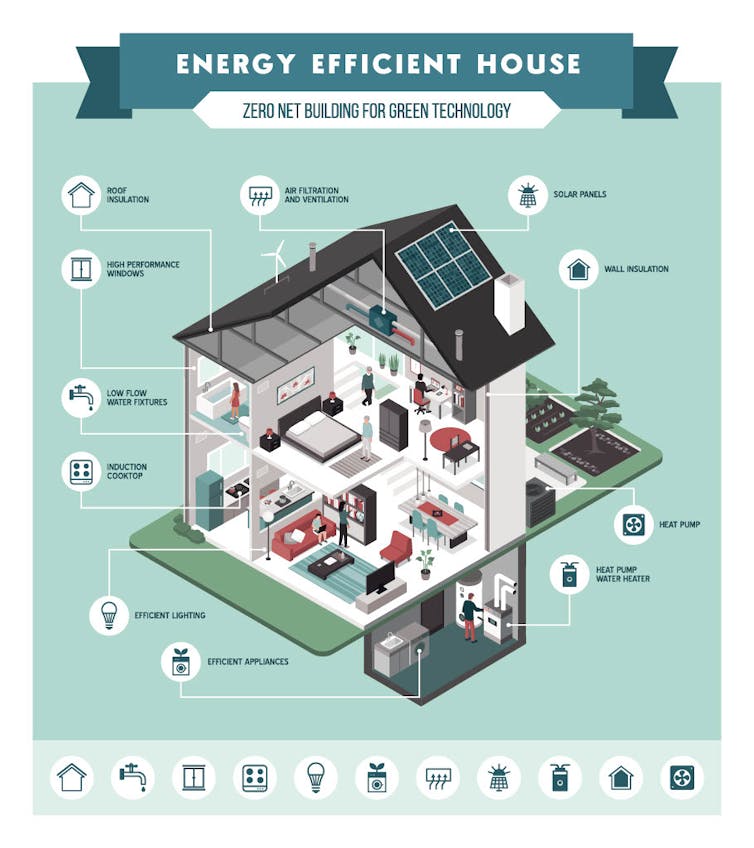

This would involve radical energy efficiency measures and the decarbonisation of heating and electricity systems, such as widespread adoption of low-carbon alternatives such as ground source heat pumps and the installation of solar panels. We estimate that if the existing homes become zero carbon by 2050, the housing system would consume 38% less of the carbon budget than currently forecast.

Tackling the emissions from new homes is more complex. The conventional narrative surrounding the housing crisis is that it is caused by a shortage of housing. This creates a trade-off between the climate and the social priority of building homes.

Consecutive governments have reacted by accelerated housing construction. This resulted in there being 1.2 million more houses in England than there were households in 2019. Despite this, homes cost 314% more on average in August 2022 than in January 2000.

Why is housing so expensive?

The financial dynamics of the English housing market and inequality of access to it offer an alternative explanation for the crisis.

Financial deregulation and liberalisation in the 1980s made it much easier for a wider range of people to get mortgages. Mortgage lending quadrupled from roughly 15% of the UK’s GDP in the 1960s to around 60% by 2008. With more credit flowing towards an inelastic supply of new housing, the unsurprising result was inflated house prices.

But unlike most commodities, where rising prices lead to falling demand, high house prices instead create further demand for mortgage credit as housing is also valued as an investment. This creates a positive feedback loop whereby subsequent price rises encourage people to enter the housing market to benefit from higher prices.

Domestic and foreign investors also entered the market, competing with ordinary homeowners to maintain high prices. From 2014 to 2016, 13% of all homes purchased in London were bought by overseas investors.

High house prices also exacerbate inequalities in access to housing. Buyers who already own property can secure additional mortgage loans at favourable rates, beating first-time buyers to available stock.

But many houses are unoccupied, or rarely used. Around 500,000 second homes in England have owners that do not choose to rent them out, while the amount of homes owned by people registered abroad has trebled to 250,000 since 2010.

Solutions to the housing crisis

Without addressing these issues, many new homes will remain unaffordable and continue to satisfy primarily the demands of wealthy homeowners, while locking in further carbon emissions. Only strategies that create fairer access to buying homes will ensure everyone’s housing needs are satisfied.

There are several ways to achieve this at a minimal environmental cost.

Existing housing space can be used more efficiently. By taxing second and foreign-owned homes, the over-consumption of housing could be discouraged. The impact on demand would reduce prices and release stock onto the market.

Taxation has been used to curb soaring house prices in Canada. In 2016, British Columbia’s government imposed a 15% tax on foreign entities buying residential property in Vancouver. Research indicates that this tax reduced house prices in Vancouver by 5% from 2016 to 2017.

Accelerating the construction of new social housing to cater specifically for those who could not otherwise afford housing is another method. New construction should also conform to strict emissions standards to avoid adding future decarbonisation costs.

Economy based on house prices

But England’s economy is structurally dependent on house price rises. Measures to restrict financial speculation and release existing housing space to meet ordinary people’s needs receive little attention in government policy.

Almost half of all bank assets in the UK are tied up in property. Falling house prices would have serious implications on the financial sector’s willingness to provide credit.

Many homeowners have also gambled on rising housing prices to justify large mortgage debts or to ensure decent assets for themselves for when they retire.

Homeowners also represent 63% of the population, according to figures from 2018, and are a powerful political voice. The UK property lobby, for example, donated over £60 million to the Conservative party from 2010 to 2020. There is a clear political incentive to maintain high house prices, with political parties in direct competition for the support of homeowners.

There are political and economic barriers to moving towards fairer housing policies. But these challenges are not insurmountable. One way would be to reform the pensions system to reduce individuals’ dependence on house prices for their financial security.

In combination with measures to retrofit the existing stock it would be possible to move towards a future where society’s housing needs are met without exceeding environmental limits.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.