Brazil’s president-elect, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, was greeted with applause and cheers when he addressed the U.N. climate conference in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, on Nov. 16, 2022. As he had in his campaign, Lula pledged to stop rampant deforestation in the Amazon, which his predecessor, Jair Bolsanaro, had encouraged.

Forests play a critical role in slowing climate change by taking up carbon dioxide, and the Amazon rainforest absorbs one-fourth of the CO2 absorbed by all the land on Earth. These articles from The Conversation’s archive examine stresses on the Amazon and the Indigenous groups who live there.

1. Massive losses

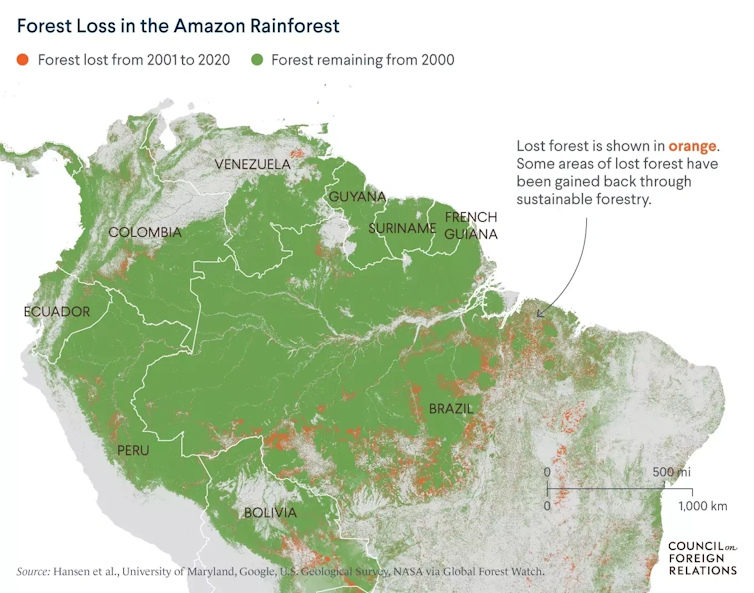

The Amazon rainforest is vast, covering some 2.3 million square miles (6 million square kilometers). It extends over eight countries, with about 60% of it in Brazil. And the destruction occurring there is also enormous.

From 2010 to 2019, the Amazon lost 24,000 square miles (62,000 square kilometers) of forest – the equivalent of about 10.3 million U.S. football fields. Much of this land was turned into cattle ranches, farms and palm oil plantations.

“There are a number of reasons why this deforestation matters – financial, environmental and social,” wrote Washington University in St. Louis data scientist Liberty Vittert, explaining why she and other judges chose Amazon deforestation as the Royal Statistical Society’s International Statistic of the Decade.

Forest clearance in the region threatens people, wild species and freshwater supplies along with the climate. “The farmers, commercial interest groups and others looking for cheap land all have a clear vested interest in deforestation going ahead, but any possible short-term gain is clearly outweighed by long-term loss,” Vittert concluded.

À lire aussi : Statistic of the decade: The massive deforestation of the Amazon

2. Legalizing land grabs

Much of the Amazon has been under state control for decades. In the 1970s, Brazil’s military government started encouraging farmers and miners to move into the region to spur economic development, while also setting some zones aside for conservation. More recently, however, Brazil’s government has made it easier for wealthy interests to seize large swaths of land – including in conservation areas and Indigenous territories.

Reviewing national laws and land holdings, University of Florida geographers Gabriel Cardoso Carrero, Cynthia S. Simmons and Robert T. Walker found that Brazil’s National Congress was expanding the legal size of private holdings in the Amazon even before Bolsonaro was elected in 2019.

In southern Amazonas state, Amazonia’s most active deforestation frontier, rates of deforestation started to rise in 2012 because of loosened regulatory oversight. The number and size of clearings that the researchers identified using satellite data increased after Bolsonaro took office.

“Because of policy interventions and the greening of agricultural supply chains, deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon fell after 2005, reaching a low point in 2012, when it began trending up again because of weakening environmental governance and reduced surveillance,” they observed. “In our view, the global community can help by insisting that supply chains for Amazonian beef and soybean products originate on lands deforested long ago and whose legality is long-standing.”

À lire aussi : The great Amazon land grab – how Brazil's government is clearing the way for deforestation

3. Indigenous resistance

Road building in the Amazon, which increased dramatically during Bolsonaro’s tenure, brings development and related threats like wildfires into wild areas. University of Richmond geographer David Salisbury also saw it as an existential threat to Indigenous communities.

Indigenous residents of the Brazilian-Peruvian borderlands where Salisbury worked “understand that the loggers and their tractors and chainsaws are the sharp point of a road allowing coca growers, land traffickers and others access to traditional Indigenous territories and resources,” Salisbury reported. “They also realize that their Indigenous communities may be all that stands in defense of the forest and stops invaders and road builders.”

Several Indigenous women won office as federal deputies in Brazil’s recent elections, and Lula has pledged to protect Indigenous people’s rights. Salisbury saw it as crucial to ensure that Indigenous defenders of the Amazon receive “the support and educational opportunities needed to be safe, prosperous and empowered to protect their rainforest home.”

À lire aussi : Indigenous defenders stand between illegal roads and survival of the Amazon rainforest – Brazil's election could be a turning point

4. Five global deforestation drivers: Beef, soy, palm oil, wood – and crime

A small handful of highly lucrative commodities are the main causes of deforestation in the Amazon and other tropical regions around the world. In Brazil, much of the land is cleared for raising beef cattle or cultivating soy. In Indonesia and Malaysia, palm oil production is spurring large-scale rainforest destruction. Wood production, for pulp and paper products as well as fuel, is also a major driver in Asia and Africa.

“Making the supply chains for these four commodities more sustainable is an important strategy for reducing deforestation,” wrote Texas State University geographer Jennifer Devine. But Devine also found a fifth factor interwoven with these four industries: organized crime.

“Large, lucrative industries offer opportunities to move and launder money; as a result, in many parts of the world, deforestation is driven by the drug trade,” she reported. In the Amazon, for example, drug traffickers are illegally logging forests and hiding cocaine in timber shipments to Europe.

“Promoting sustainable production and consumption are critical to halting deforestation worldwide. But in my view, national and industry leaders also have to root organized crime and illicit markets out of these commodity chains,” Devine concluded.

À lire aussi : Organized crime is a top driver of global deforestation – along with beef, soy, palm oil and wood products

Editor’s note: This story is a roundup of articles from The Conversation’s archive.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.