Djafaruddin says he has recovered from the trauma of collecting bodies when the world's deadliest tsunami devastated Indonesia's western coast two decades ago, but he still breaks down when thinking about the orphaned children.

The resident of worst-hit city Banda Aceh jumped in his black pickup truck to shift dozens of the dead, some missing limbs and others crushed, to a nearby hospital, leaving him covered in blood and mud.

"When I saw the condition in the river with bodies strewn about... I screamed and cried," he said.

"I said 'what is this? Doomsday?'"

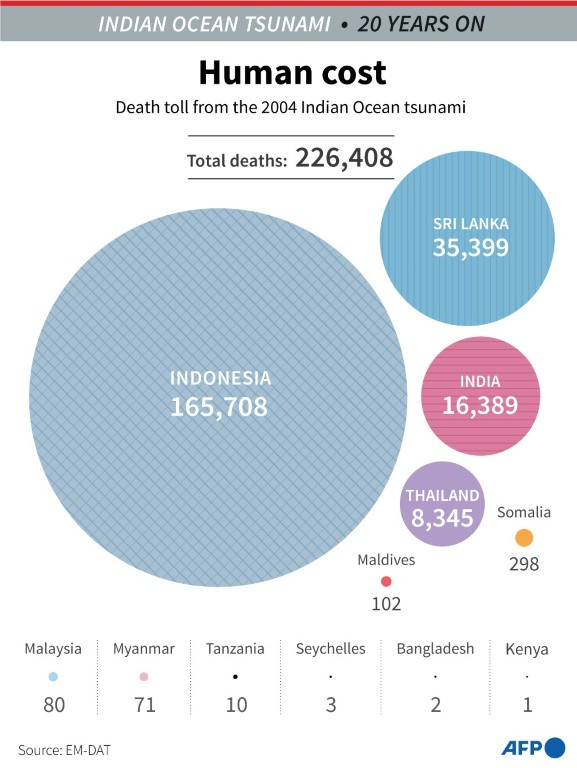

A 9.1-magnitude quake near Sumatra island on December 26, 2004 caused the biggest faultline fracture ever recorded, pushing giant waves into the sky and killing more than 220,000 people in 14 countries.

The sight overwhelmed Djafaruddin, a 69-year-old who like many Indonesians goes by one name, as he embarked on a voluntary mission to retrieve fellow locals.

"It is just unimaginable that this could happen. It was as though this was the end of the world," he said.

He returned to where he pulled dead bodies out of the debris after the giant waves indiscriminately swept away the old and the young.

"This is where corpses laid, mixed with woods carried by the currents," he said at a corner near Banda Aceh's Baiturrahman Grand Mosque, where he collected the bodies of at least 40 victims.

"I saw children, picking them up as if they were still alive, just to find them limp and lifeless."

Indonesia was the worst-hit country with more than 160,000 killed, although the true death toll was thought to be higher as many bodies were never recovered or identified.

Aceh's provincial capital today is abuzz with scooters and tourists, but Djafaruddin described a completely different scene when the giant wave tore through its streets.

"Here, we saw fathers and mothers who cried, looking for their wives, looking for their husbands, looking for their children," he said.

Then a transportation agency official, Djafaruddin was at home when waves more than 30 metres (98 feet) high struck his city.

As his road filled with people escaping, he instead went towards the disaster.

His son returned from the city centre screaming, "the water is rising!" but the father-of-five told his family to stay put, knowing the water wouldn't reach his home five kilometres (three miles) from shore.

Elsewhere entire communities by the shore were wiped out by a disaster many had not heard of before or expected.

He jumped in his car which was usually reserved for carrying traffic lights and road signs.

It would soon fill up with human bodies.

"It was just a spontaneity. It occurred to me that we should help," he said.

He became one of the first people to arrive at a military hospital in the city with tsunami victims.

As recovery efforts intensified, he was later joined in the day by the army and Indonesian Red Cross, making journeys back and forth to the hospital.

When he made a final, exhausted stop at the hospital around dusk after a day of retrieving bodies, health workers offered him bread and water because of his haggard appearance.

"Because our bodies were covered in blood and mud, they fed us," he said.

He suffered trauma for years after the tragedy yet feels he has recovered two decades on because "it has been a long time".

But he broke down remembering children who called out for their missing parents.

The volunteer and his family took in dozens of children after they ran away from the rising waters, many traumatised by the disaster.

"It was really sad. We saw them screaming at night, calling for their parents," Djafaruddin said, sobbing.

They later transferred the children to evacuation shelters across the city.

"We don't need to be sad. We let them go. I think all Aceh people think like that," he said.

He now serves as head of a village in Banda Aceh, calling the position a "service for the people".

And he believes the disaster was a "warning" from God after a decades-long separatist conflict with the Indonesian government that was resolved after the tragedy.

Whenever he passes the spot where he collected those lifeless bodies decades ago, he says it reminds him of his efforts that day.

Staring at the ground, he prayed for the victims of the waves.

"O Allah, my God," he said. "Give them heaven."