Carolyn Bryant Donham, the white woman who accused Black teenager Emmett Till of making inappropriate advances toward her in 1955, has died at the age of 88 in Louisiana, according to a coroner’s report.

Nearly 68 years after Till was kidnapped, brutally tortured, murdered and then dumped into the Tallahatchie River in Mississippi, the case continues to resonate with audiences around the world because it represents an egregious example of justice denied.

As a historian of the Mississippi civil rights movements, I quickly learned that most Mississippi civil rights history leads back to the widespread outrage over the Till case in the summer of 1955.

Emmett in Money, Mississippi

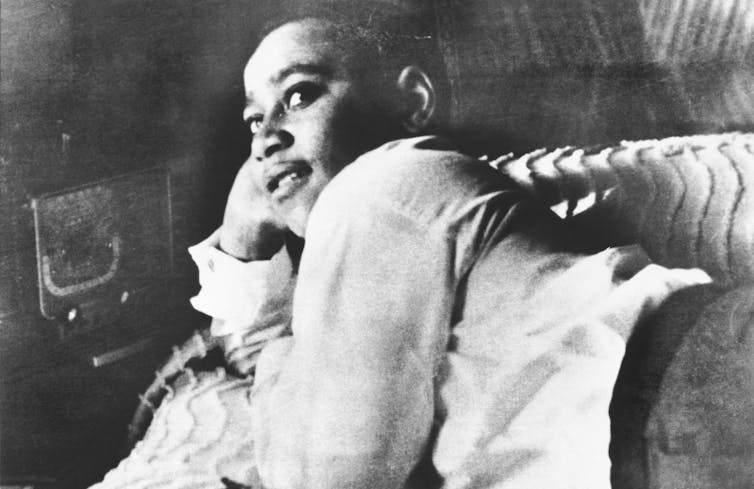

Fourteen-year-old Emmett arrived in Mississippi on Aug. 20, 1955, from Chicago to visit his mother’s family, who sharecropped cotton in the tiny Delta community of Money.

On the evening of Aug. 24, Emmett and several cousins and neighbors drove the 2.8 miles into Money to buy candy at the Bryant Grocery and Meat Market.

Emmett entered the store alone. He bought 2 cents’ worth of bubble gum and left. At the door Emmett let out a loud, two-note wolf whistle directed at white 21-year-old Carolyn Bryant. His cousins were terrified: Emmett had just hit the trip wire of Southern racial fears by flirting with a white woman.

Early on Aug. 28, several men – white and Black – took Emmett from his family’s house. Emmett’s badly decomposed and battered body was discovered three days later in the Tallahatchie River. Emmett’s uncle could identify Emmett only by a ring he was wearing that once belonged to Emmett’s father, Louis Till.

Two white men, Roy Bryant and J. W. Milam, were quickly arrested and later charged with murder. During a five-day trial in September, the two men were found not guilty after a 67-minute deliberation by an all-white, all-male jury.

Several years later, members of the jury confessed to a Florida State University graduate student, Hugh Stephen Whitaker, that they knew the men were guilty but simply wouldn’t convict a white man of crimes against a Black child.

In 1956, Milam and Bryant sold their “shocking true story” of what happened to Till for US$3,150 to Look magazine. For nearly 50 years, celebrity journalist William Bradford Huie’s “confession” story in Look functioned as the final word on the case.

Continued interest and coverage

Southern newspapers wanted immediately to forget the Till story, ashamed of the backlash caused by Milam and Bryant’s “confession.” Many Northern and Western newspapers editorialized on the case long after its conclusion. America’s Black press never quit writing about the case; it was their work, after all, helping to track down Black eyewitnesses in September 1955 that helped us understand the truth of what actually happened to Emmett Till on Aug. 28, 1955.

Thanks to investigative work by documentary filmmaker Keith Beauchamp and others, the public has since learned that Milam and Bryant were part of a much larger lynching party, none of whom were ever punished.

Today, all of the people directly involved in Till’s murder are dead.

A case that aged with Carolyn Bryant Donham

The last 20 years of Bryant Donham’s life were characterized by the attempt of private citizens and law enforcement to bring her to justice for the part she played in Till’s kidnapping and murder.

When Bryant Donham was in her 80s and living with family in Raleigh, North Carolina, FBI investigators and federal prosecutors revisited her case and the potential for prosecuting her for Till’s kidnapping and death. One question was whether Bryant Donham recanted her previous testimony about Till’s advances and said that it was false.

A historian said in 2017 that Bryant Donham told him in a rare interview that the most egregious parts of the story she and others told about Emmett Till were false.

The Justice Department said in 2021, though, that it was unable to confirm whether Bryant Donham actually went back on her previous testimony, and it closed the case.

Then, in 2022, a team of researchers – including two of Till’s relatives – discovered an unserved arrest warrant for Bryant Donham in a courthouse basement. This led some legal experts to say that the 1955 document could support probable cause to prosecute Bryant Donham for her involvement in Till’s death.

Mississippi’s attorney general said in 2022 that the office did not plan to prosecute Bryant Donham – though that didn’t stop activists from protesting outside her home that same year.

Recently unearthed documents also showed that Till did not put his hands on her nor talk lewdly to her in the store. That was all fabricated as part of the defense’s strategy to argue that the lynching amounted to justifiable homicide. When the presiding judge, Curtis Swango, did not allow the jury to hear Bryant Donham’s testimony, the defense pivoted to the absurd claim that the body taken from the Tallahatchie River wasn’t Till’s.

Over the past several decades, the Till case has continued to resonate, especially for a nation that still experiences the all-too-frequent and seemingly unprovoked deaths of young Black men. The Till family has had to live with an open wound for 68 years. As Devery Anderson, author of “Emmett Till: The Murder That Shocked the World and Propelled the Civil Rights Movement,” has noted, that wound won’t suddenly go away with Bryant Donham’s passing.

This is an updated version of an article originally published on July 13, 2018.

Davis W. Houck does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.