On September 28, 2008, Elon Musk and SpaceX altered the history of the cosmos. On that fateful day, the then-struggling company sent the first privately developed liquid-fuel rocket — Falcon 1 — into orbit.

The launch set off a domino effect, sparking the growth of other companies aiming to launch rockets and satellites more quickly and cheaply than the government agencies and contractors that had run the game since Neil Armstrong's “giant leap for mankind.”

That’s the argument made by tech journalist and author Ashlee Vance in his new book When the Heavens Went on Sale: The Misfits and Geniuses Racing to Put Space Within Reach. Vance is intimately familiar with Elon Musk — he released a biography on the infamous tech mogul in 2015.

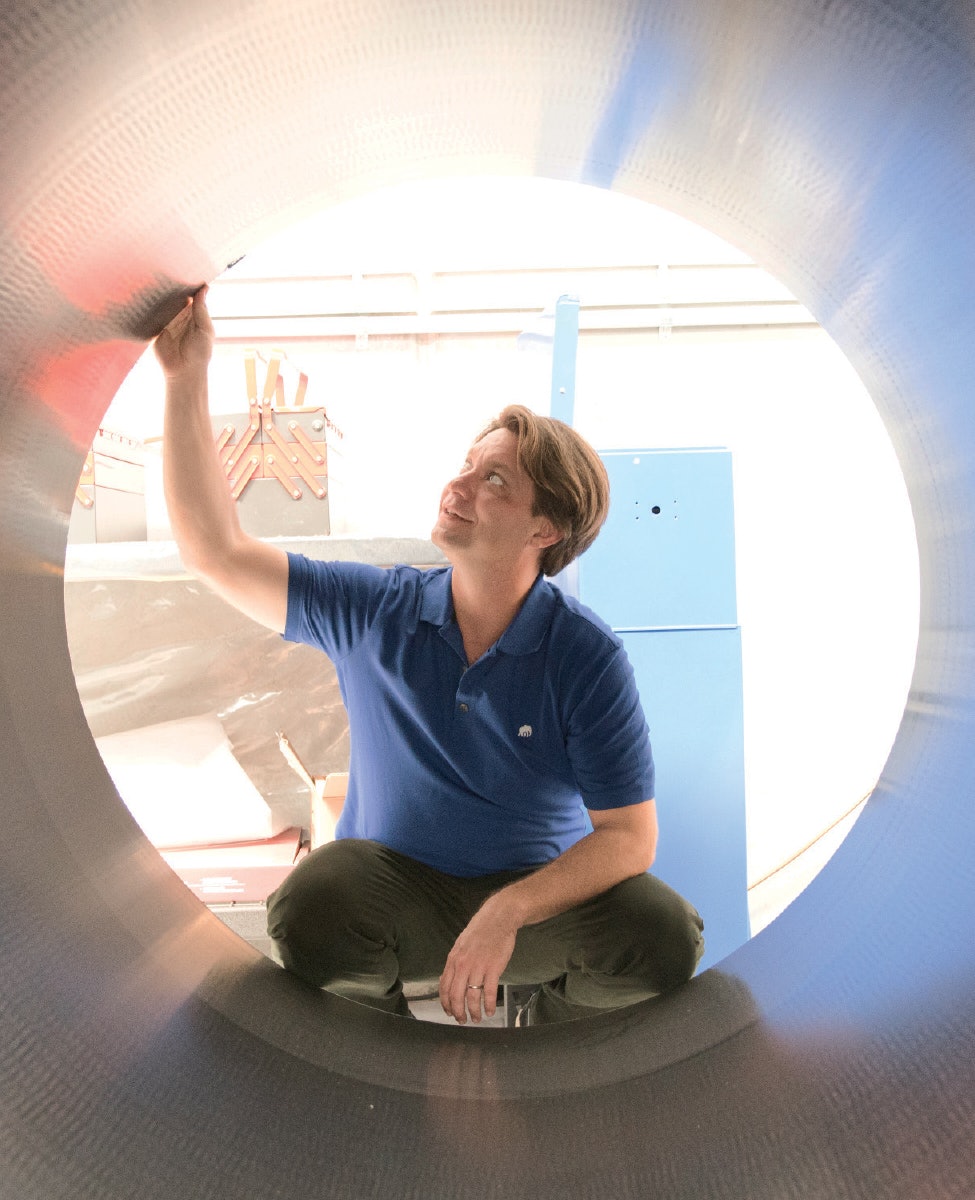

In fact, his in-depth Musk reporting introduced Vance to the colorful cast of characters profiled in his recent work. When the Heavens Went on Sale spends little time on SpaceX, dedicating most of its pages to Musk-inspired space companies that aim to quickly deploy rockets and satellites to low-Earth orbit: California-based Astra, Rocket Lab, and Planet Labs, along with Texas-based Firefly. With more than five years of reporting, Vance followed these teams everywhere, from New Zealand to French Guiana, stepping into secret launch locations and witnessing armed bodyguards, whisky-fueled tiffs on private planes, and even a team of male strippers in the process.

Now, two decades past SpaceX’s founding, Vance recounts the trials and tribulations — including plenty of expensive rocket explosions — faced by these entrepreneurs in their quest to profit off our planet’s orbit and usher humanity deeper into the Universe.

Inverse spoke with Vance to learn more about his reporting — and what he predicts for the coming decades of the rapid-fire commercial space race.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

What inspired you to write this book and specifically focus on Astra, Rocket Lab, Planet Labs, and Firefly?

I guess it was an accident in some ways. I'm not a space junkie by nature. But coming out of doing the Elon Musk biography, my favorite reporting was about the early days of SpaceX and how weird and hard it was for a team of 20-somethings to build a rocket. Right as I was finishing that book, I could see all around the world, there were more groups like this trying to give this a go.

I just got sucked in. The characters turned out to be better and better than I ever could have expected. The story seemed kind of stranger than fiction. I didn't want to be pigeonholed as a space reporter, but I couldn't resist the story.

This was always meant to be an entertaining, fun read — this journey around the Earth. The focus is more on the extraordinary and unusual people than on the business itself. It's definitely not a business book.

What were your favorite moments you witnessed while embedded with these eccentric companies?

It's a very secretive world, and a lot of it is controlled by military regulations and things like that. Almost every room I was in was some kind of secret room. These companies like to remain very private.

There are two moments that really jump to mind. I spent many weeks in Kodiak, Alaska, waiting for an Astra rocket to launch. We were in this lodge, kind of trapped there with these people struggling with a rocket and with whales going by outside and bears near the house. It turned a little bit into The Shining as things went wrong.

And I am one of, I think, only two foreign reporters that ever got to go to the old Soviet intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) factory in Ukraine. I think I'm the only one that's ever been to the secret rocket testing sites in the forests of Ukraine. As a person who grew up during the Cold War, it was amazing to be at this site that was meant to spell my doom and destruction at one point.

Right, private space companies are notoriously tight-lipped. So how did you get such a close look at their inner workings?

In the case of Astra, I was there the second the company started, with the first handful of employees in a room trying to test-fire their engines for the first time. I knew all 50 employees by name, and I had my own access to the factory. The CEO, Chris Kemp, to his credit, told everybody just to tell me the good or the bad. I lived with them in Alaska and in this factory.

They built this rocket, which is not dissimilar from an ICBM missile, just about 1,000 yards from a residential neighborhood in Alameda, California. I had this front-row seat to a missile coming to life in a neighborhood that nobody else knew anything about.

Entrepreneurs like Musk and Rocket Lab’s Peter Beck claim that their rockets and satellites can outperform government operations, but they still receive billions of dollars in federal contracts and subsidies. Would it be more accurate to call this the era of public-private cooperation?

We're in a work-in-progress stage where government and military contracts are keeping some of these companies afloat during tough times, and they're still paying for a lot of missions. There are a couple of data points that I look at, though: By 2020, we had about 2,500 active satellites in low-Earth orbit* — the majority of which would have been the result of government or scientific or military funding.

In just the last three years, we've more than doubled that number, and almost all of those new satellites are commercial. SpaceX, with its Starlink space internet system, has more satellites than any country, and Planet Labs is second. This flip is happening very quickly, and even though some government funding helped some of these things happen, this is just the tipping point. We're shortly going to go into 100,000 satellites in low-Earth orbit, of which almost all will be commercial.

Elon Musk has said that SpaceX’s Starlink helps him raise money for the massive Starship rocket — do you think other businesses are using their satellite cash to fund bigger projects, too?

They almost all have to. The dirty secret of aerospace is that everybody wants to build a rocket, and it’s somehow seen as the sexiest part of all this, but it's the absolute worst business to be in.

All of the money is in the satellites and data communication services, and the vast majority of SpaceX’s valuation from its private investors is tied up in Starlink.

Rocket Lab, the rival to SpaceX, is already making around 90 percent of a satellite, so other companies don't have to repeat all of that work every time. These other startups can now just put their special bit of equipment, their sensor, or their scientific experiments, onto the satellite.

I think this is the direction almost all the rocket companies will have to go in. It just builds on my thesis that this industry is starting to look much more like a regular business, where it matures, and everybody is not building everything from scratch every time. Now, there are regular suppliers for different parts of the whole process.

How do you think Elon Musk’s Twitter era and the recent technical mishaps at Tesla affect people's hopes for SpaceX?

One of the funniest things about Elon’s career is that SpaceX should be the riskiest, worst-performing one of his companies. It's the hardest industry, and it’s taking giant swings and just shouldn't work as well as it does. But it's the clearest winner of the bunch: SpaceX is now the dominant player in space. They send up more rockets than any other country or company, and they have already put up more satellites than anyone has in history.

The company has shown its ability to run extremely well, no matter what Elon does. And, of course, Gwynne Shotwell has been the president this entire time and is this amazing right-hand woman to Elon and has run the company exceptionally well.

What do you think is the long-term goal for moguls like Jeff Bezos and Musk, who have claimed they want to form lasting human settlements in space — is it to escape climate disaster on Earth?

The commercial space industry really gets to the heart of what we want to be as a species. Do we want to stay here and try to fix up the planet? Or do we want to give in to this exploratory nature — do we think human intelligence’s goal is to spread out through the Universe? It’s so fascinating to see businesses tied to these almost mythological quests.

So far, we've seen that, among the billionaires, each one has their own thing that they're after. But I think this is all coalescing around something that's a little more pragmatic: These businesses will just be built step by step. We're not sure how many of these business cases will actually check out. But what I argue in the book is that we're about to find out.

*The Union of Concerned Scientists reported around 2,666 operational satellites in April 2020, with 1,918 in low-Earth orbit.