On June 8 1835, 188 years ago today, pastoralist John Batman crossed the Bass Strait and arrived on the shores of Naarm (now Melbourne city), on Kulin lands. His Irish-born convict wife, Eliza Batman, and their seven daughters arrived at Port Phillip the following year.

They had come from Van Diemen’s Land (Lutruwita/Tasmania), bringing 30 servants with them, including convicts, two Aboriginal boys, and Aboriginal men from New South Wales, known as the “Sydney Natives”.

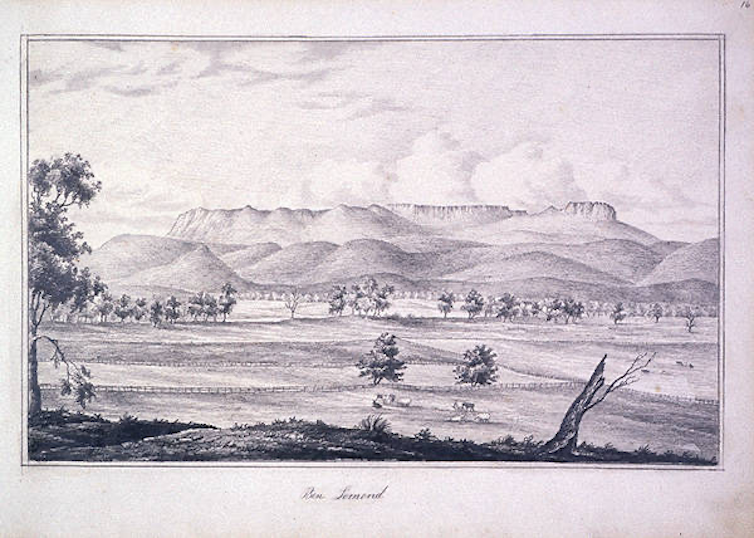

Seeking land, the Batmans moved their large pastoral enterprise with this group of convicts and Aboriginal people to what is now known as Batman’s Hill overlooking the Yarra River. The two young Palawa boys who travelled with them from Tasmania were Rolepana, whom the Batmans had named “Ben Lomond”, and Lunnerminner, or “Jack Allen”.

In the midst of Tasmania’s Black War and once in Port Phillip, the Batmans would be entangled with Aboriginal people across two violent frontiers.

Read more: Noted works: The Black War

At Melbourne’s centenary of his landing in 1935, John Batman was celebrated as an intrepid settler and the city’s founding father. Eliza Batman, however, has remained largely a footnote to this contested history. Was she a founding colonial mother? How should we remember her? What happened to her children and the Palawa boys who became part of the larger Batman pastoral “family” enterprise, forced to travel across the Bass Strait to Port Phillip?

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, monuments, roads and parks were dedicated to John Batman. At one time, it was even proposed that Melbourne be named Batmania in his honour. By the late 20th century, Batman had become problematic: his dark deeds in Tasmania as leader of the Ben Lomond massacre had entered public consciousness and debate.

Since then, there has been much controversy around Batman as Melbourne’s founding father and his place in public memory. The Batman sculpture once on Collins Street no longer stands in the Melbourne CBD. The Australian Electoral Commission renamed the inner-city federal seat of Batman in honour of the Aboriginal rights campaigner Yorta Yorta leader William Cooper.

Eliza Batman is missing in these public debates around colonisation and the politics of memorialisation. Too often frontier violence is understood as male, martial, and situated on remote borderlands. Yet, colonial violence is not only racialised, but gendered and intimate. It is close to home, and all too often occurs between those known to each other.

Popular histories have excluded Eliza and her family almost completely from these stories of colonial Tasmania and Victoria. She has often been dismissed as a low-class, illiterate doxy and drunken convict who died an ignominious death while living under a pseudonym in a rooming house in Geelong in 1852. Yet Irish-born Eliza (then Elizabeth Callaghan) from County Clare was literate and astute.

We’ve been interested in Eliza Batman for a long time. In the late 1990s, we drove to Geelong on a dusty, hot January day to find Eliza’s grave at the cemetery, which was then unmarked. Although her actual grave remains somewhere in the paupers section, Eliza is memorialised in a plaque alongside that of her seventh daughter, who bore the curious name Pelonamena. Looking more deeply, we found that the Batmans named their seventh daughter after an Aboriginal woman, “Pellonymyna”.

We do not seek to rehearse the popular notion of John Batman – or Eliza – as the founders of Melbourne, or of a triumphal Bass Strait crossing of a founding family from Van Diemen’s Land to Port Phillip. Rather, we wish to reveal other crossings in looking at the Batmans.

Our research into Eliza Batman and her colonial home opens uncomfortable vistas onto the pastoral frontier where colonial women, forced kinship, affection and violence were bound together.

Read more: The truth about John Batman: Melbourne's founder and 'murderer of the blacks'

Convict infamy and the iron collar

Eliza was a small woman of dark hair and brown eyes, around 5 feet and 2½ inches. In 1820, aged 17, she was tried at the Old Bailey in London for passing forged notes, a crime called “uttering”. One of her male accomplices was hanged, but Eliza’s sentence was commuted to 14 years transportation to the Australian colonies.

Eliza was transported to Tasmania in 1821 on the ship Providence with 102 other female felons. The convict indent or list made on “Elizabeth Callaghan’s” arrival in Hobart, noted “gaol report bad”.

The convict indent also records that once in Hobart she absconded from several masters. Each time she was placed in the stocks, fed bread and water, and forced to wear the iron collar, a punishment often reserved for women.

In 1820 the commandant at George Town, Colonel Cimitiere, called the iron collar “a badge of infamy and disgrace” that was the “usual Instrument throughout the Colonies which is put round the neck of women of Infamous character”.

There are no portraits or photographs of Eliza that can be found, but her likeness is suggested by the photographic portrait of her daughter Pelonamena.

Later Eliza absconded again, and was soon living under the pseudonym Elizabeth Thomson, at the property “Kingston” in the Midlands with John Batman. In early 1828 Batman requested permission from Lieutenant Governor Arthur to marry Eliza. By this time they had three daughters. Arthur approved the union, and on 29 March 1828, Eliza and John were married.

Writing Eliza

As historians, how do we write about Eliza? This can be no simple reclamation of history. Eliza was both a colonised Irish woman and a coloniser, entangled in the violent frontiers of early Australia. She was mistress to the Batman household and profited from this large enterprise in the midst of a pastoral boom and the expulsion of Aboriginal peoples from their traditional lands.

Throughout her life, Eliza negotiated harsh penal servitude, privilege and mobility as the mistress of the Batman family’s large pastoral holdings across two southeastern colonial frontiers in the 1830s. Although the convict stain followed her all her life, Eliza was not a low-class woman or prostitute as some biographers have suggested. In her final years she endured dire poverty and suffered a violent death. She was murdered in a rooming house in Geelong, while living under another pseudonym, Sarah Willoughby.

There is no entry for Eliza in the Australian Dictionary of Biography. The scant accounts of her life tend to be stereotypical. In the dictionary entry on John Batman she is framed largely as a woman of “somewhat abandoned character”, although historian P.L Brown concedes she was “an able woman” who “wrote a good letter”.

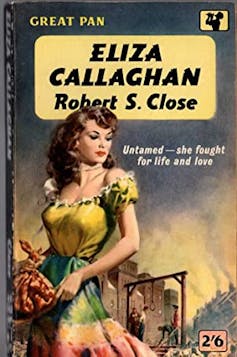

In the only dedicated account of her life, Robert S. Close’s racy novel, Eliza Callaghan (published 1957), follows Eliza from London and Newgate Gaol to her introduction to John Batman. The sensational by-line on the cover reads: “Untamed […] she fought for life and love”. Historians, mostly male, have reinvented her repeatedly, just as Eliza, in her own lifetime, reinvented herself.

Archival sources of Eliza’s voice are fragmentary. There are no diaries or collections of personal correspondence discovered to date. However, a close reading of surrounding sources reveals much about Eliza and her experiences during her life. As researchers, we find her story tests the limits of memorialisation – there are no easy narratives here.

Mistress at Kingston

In Tasmania, the Batman property “Kingston” was a large station situated on Plangermaireener Aboriginal land in the Ben Lomond region.

Batman had taken part in and profited from the Black War between Aboriginal people and settlers in Tasmania (1828–1834), as his household at Kingston became a depot and service point in the execution of “roving parties” and orchestrated attacks against Aboriginal peoples.

It is well recorded that John Batman had participated in the “Black line” and organised these “roving parties” from his property at Kingston during the genocidal war against Aboriginal peoples. It is also documented that in September 1829 he led the Ben Lomond massacre, where at least 17 Aboriginal people died in a dawn attack.

Read more: Explainer: the evidence for the Tasmanian genocide

It was during this attack that John Batman abducted the two-year-old boy Aboriginal Rolepana (renamed by the Batmans “Ben Lomond”). Batman reported afterwards to British Colonial Secretary, John Burnett, that he kept the child because he wanted “to rear it”.

During this time Lurnerminner (renamed “Jacky” or “Jack Allen”) was at Kingston. A third Aboriginal boy was also held there, renamed “John Batman”. We have not discovered what became of him.

Eliza, as mistress of Kingston, was a central part of the daily business activities of the household and station and its role as a depot for roving parties. The pastoral home, or station, was a site of colonial domesticity, but it was also an unhomely “contact zone” in which Eliza, as the mother and mistress of the household, taught the dispossessed Aboriginal boys to read and to recite the Lord’s Prayer.

Eliza had the boys baptised. On 2 June 1830, John Batman rode home to Kingston for the baptism of his four daughters and Rolepana, the survivor of the Ben Lomond massacre. In this new colonial world, Rolepana lost his Plangermaireener name.

At Kingston, the boys were used as labourers: they drove the plough, milked the cows, and tended the swine. There is some evidence that they were “flogged with a whip”. Aboriginal children like Rolepana and Lurnerminner were taken from their own families to become reincorporated into the colonial homestead as dependants and servants. They were enfolded in colonial intimacies that recast acts of aggression as acts of kindness and civilisation, and dispersal of Aboriginal families as care.

While Eliza was undeniably privileged by her race, she was also impoverished by her gender. Later in Melbourne, upon her husband’s death in May 1839, she was cruelly written out of Batman’s will and given only five pounds, leaving her destitute with eight children to care for.

A long fight ensued over the Batman will, which languished in the shadow of Melbourne’s chancery court. Eliza eventually lost her home and much of the family’s land holdings. Her young son, Charles Batman, had died. She could not support her daughters, so they were separated and sent to the households of friends around Port Phillip.

By contrast, John Batman’s death left the two young Aboriginal boys, Lurnerminner and Rolepana, without access to the network of support that was available to the Batman children. These boys from Tasmania were left largely to fend for themselves in Melbourne.

Rolepana went on to work for colonist George Ware, but died in Melbourne in 1842. Lurnerminner went to sea and worked on whaling ships, perhaps claiming a kind of freedom offshore that was not possible onshore. He later returned to Tasmania to live at Oyster Cove Aboriginal Station, south of Hobart.

Pellonymyna

There is another hidden woman in this story: the Aboriginal woman named Pellonymyna. Names are touchstones in the poetics of memorialisation, and their use and exchange, especially across cultures, can be potent. While Rolepana lost his Plangermaireener identity to be christened “Ben Lomond”, the Batmans’ seventh daughter claimed a Plangermaireener name.

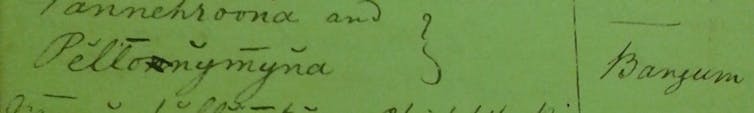

In July 1834, Eliza gave birth to this daughter. The Batmans named this child Pelonamena Frances Darling Batman, after Pellonymyna, or Pellenominer, an Aboriginal woman from Ben Lomond.

In the midst of the land war, Pellonymyna was incarcerated at Flinders Island Aboriginal station, along with others, and placed under the guardianship of the commandant, Frances Darling. Darling was well known to the Batman family, and it seems this appellation was made partly in his honour.

Travelling Quakers James Backhouse and George Washington Walker also met Pellonymyna on Flinders Island, and her name appears in Walker’s unpublished journal in a list of Aboriginal people held there. On the surface, this naming appears be a mark of affection and reciprocal exchange. But it is a disquieting gesture to the Plangermaireener people the Batmans aggressively displaced. The Aboriginal woman, Pellonymyna (also known as Bangum or Flora), was later sent to the Oyster Cove Aboriginal Station, south of Hobart.

This exchange of a name is an example of the uneasy ways forced colonial kinships were made and memorialised under the sign of home and family. It was through these apparently familial vectors of imperial power – where land, homes and children and names were taken from Aboriginal people – that everyday domestic yet unhomely relationships were forged on southeastern frontiers.

In 1851 Eliza’s daughter, Pelonamena Frances Darling Batman, married Port Phillip resident Daniel Bunce, who later became director of the Geelong Botanical Gardens. Together they had two infant children, although neither survived past one year. Pelonamena died at the age of 25.

Across all the southeastern colonies European women and men were making homes – and at the same time Aboriginal people and families were losing their homes, land and children.

These gendered, domestic borderlands of colonialism in Australia still require far more historical scrutiny. The politics of their memorialisation will always be challenging.

Penny Edmonds receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

Michelle Berry does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.