Over the years, Pixar has forged memorable characters out of abstract concepts such as emotions, memories, or even the soul. But for their upcoming new feature, Elemental, they faced their greatest hurdle yet: creating characters made out of fire, water, earth, and air.

“Elemental was entirely unique and it required us to work a bit backwards,” production designer Don Shank said. “Our technical abilities informed and inspired design choices. And then those design choices in turn, inspired new technology, which then inspired new designs.”

In Elemental, a fire element Ember Lumen (Leah Lewis) and a water element Wade Ripple (Mamoudou Athie), live in a city where fire, water, land and air residents all exist side-by-side. But each element keeps to their own — except for Ember and Wade, who discover that they have more in common than they think.

“Ember is fire. She's not something on fire. Wade is water. He's not something wet.”

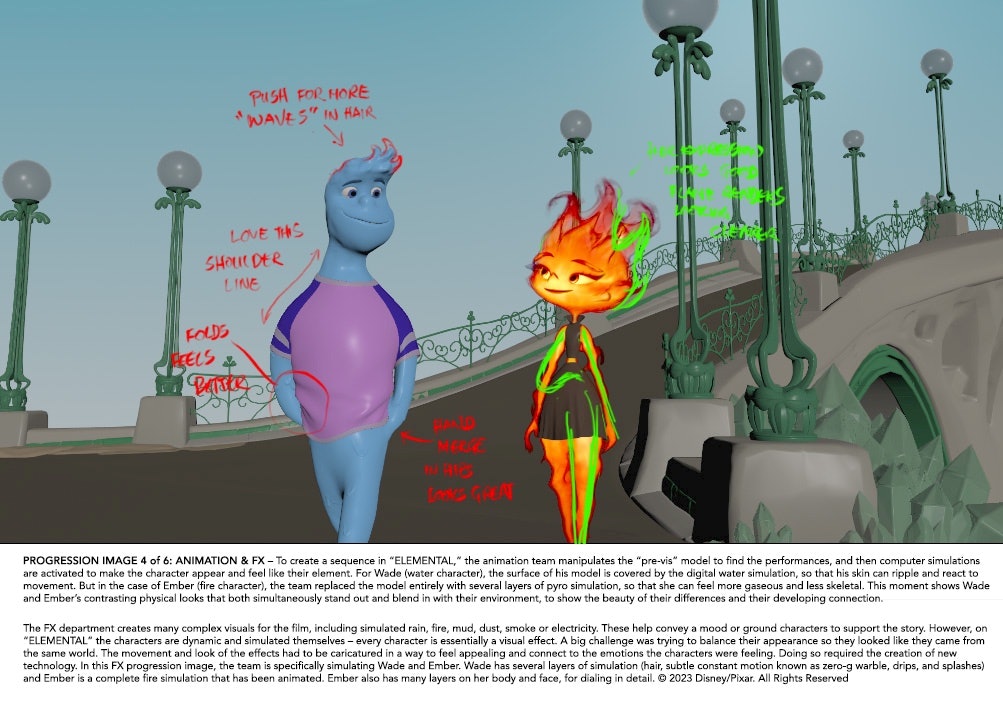

Ember, the female protagonist, and Wade, her male counterpart, are unlike anyone Pixar has animated before. Their bodies are distinct from others because they are comprised of visual effects that replicate, as vividly as possible, how fire and water, respectively, behave. The concept required the team to understand that “Ember is fire. She's not something on fire. Wade is water. He's not something wet,” as Jeremy Talbot, character supervisor of modeling and rigging, put it.

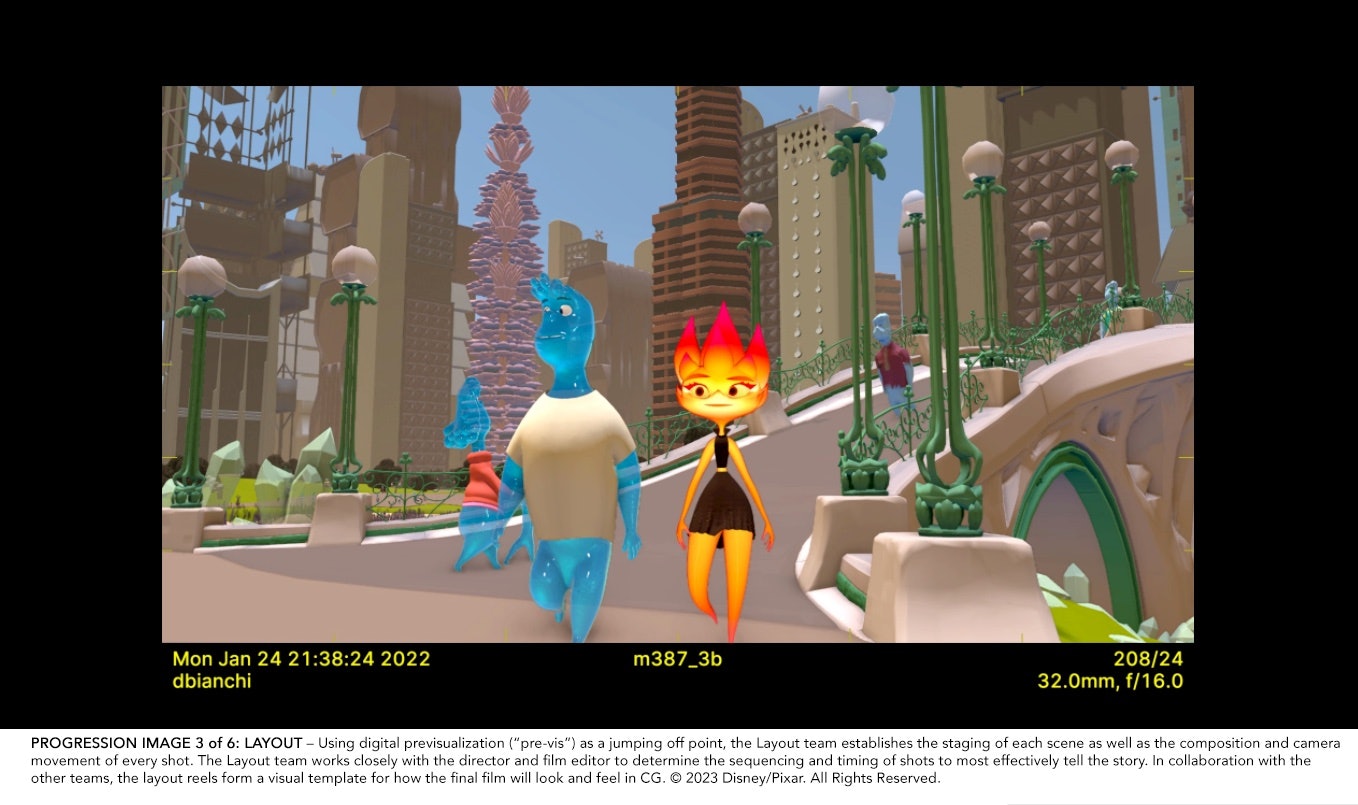

During a recent press event hosted at the Pixar campus in Emeryville, California, Elemental director Peter Sohn (The Good Dinosaur) and a group of craftspeople and technicians from across multiple departments in the production offered a rundown of some of the film’s practical demands and how they overcame them with the meticulous ingenuity that Pixar has become famous for.

A Concept Somewhere Between Science and Art

First, there was a dialogue between the art and technical teams about the design of the characters in order to eventually visualize a world they could naturally inhabit. Production designer Don Shenk described the look resulting from those conversations and numerous tests as “a delicate balance between physics, logic, and cartoony appeal.”

In their pursuit of a middle ground between realism and stylization, the technical crew studied the physical properties of fire and water in order to devise tools that would help the animations pose the characters and control their performances.

Details like the ripples in Wade’s face, the shifting quality of Ember’s flame, and the residue they each leave behind with every motion (in droplets or licks) enhanced their expressiveness. An early scene, in footage shown to press, sees Ember turn a purple hue to denote she is about to lose her temper, while Wade weeps profusely with exaggerated tears pouring out his eyes.

How Does Fire Move?

Each element moves in a distinct manner depending on their weight, flexibility, and fluidity. With such malleable figures, animators had to constantly think of how a human would carry out a certain action and then imagine how water or fire would do it. Early on, they enlisted artists with experience in 2D animation to figure out what a walking flame might look like.

“Fire was looser, lighter, and more gaseous, which gave Ember the freedom to change scale and volume more easily. There's a softer quality to her motion, and she has an upward drafting energy,” said directing animator Allison Rutland. “In contrast, water is a much heavier force that retains its volume en mass. That downward gravity made Wade more grounded in his contact and it gave lots of fun and playful opportunity for sloshy watery overlap,” added fellow directing animator Gwen Enderoglu.

“As Pixar animators, creating emotionally truthful performances is our top priority.”

While experimenting with these attributes, they discovered that Ember's fire seemed more believable if they made her transitions between poses look more spontaneous. As she moves, her “limbs change shape, they disappear, and reform like trailing fire.” If her movement appeared too human-like or still, she would resemble a statue on fire.

Animators had to think about all these details to keep characters feeling fluid and not human. Ember and Wade each had roughly 10,000 individual animation controls providing animators a large toolbox to meet the needs of every shot for exaggeration or subtly.

“As Pixar animators, creating emotionally truthful performances is our top priority. And on Elemental we had a new layer to weave into these emotional performances, tying the energy of an emotion directly to the physical property of an element,” said Enderoglu.

For example, Ember’s fire becomes more active and changes color to match her emotional state with her appearance. With a change in brightness, for example, they could imply the intake of oxygen to create a fiery laugh. Animators could also increase or reduce the speed of her flames to express a particular mood.

This Time, the Effects Came Early

The singular nature of the characters in Elemental, forced Pixar to rethink when the effects department would get involved. As effects supervisor Stephen Marshall explained, on a typical Pixar project, his team wouldn’t start working until after the characters had been designed and animation had been completed.

Usually, their main concern is to add explosions or create destruction in a scene without obscuring character performance; however, on this film they came in during its early development and collaborated closely with the shading department (in charge of colors and textures) to give the dynamic characters visual stability and predictability: Ember’s fire couldn’t distort her features and Wade had to preserve his hairstyle as intact as possible.

In order to achieve the desired texture on these characters, the team in charge of shading had to consider the fact that fire is self-illuminating, meaning that the fire characters are actually light sources. Water, on the other hand, is refractive and reflective, and if these qualities weren’t handled properly, you could see the back of Wade’s eyes and teeth, which made for a realistic, but terrifying sight. This reinforces the notion that straightforward realism wouldn’t cut it, and at times the need for relatable characters trumped physics.

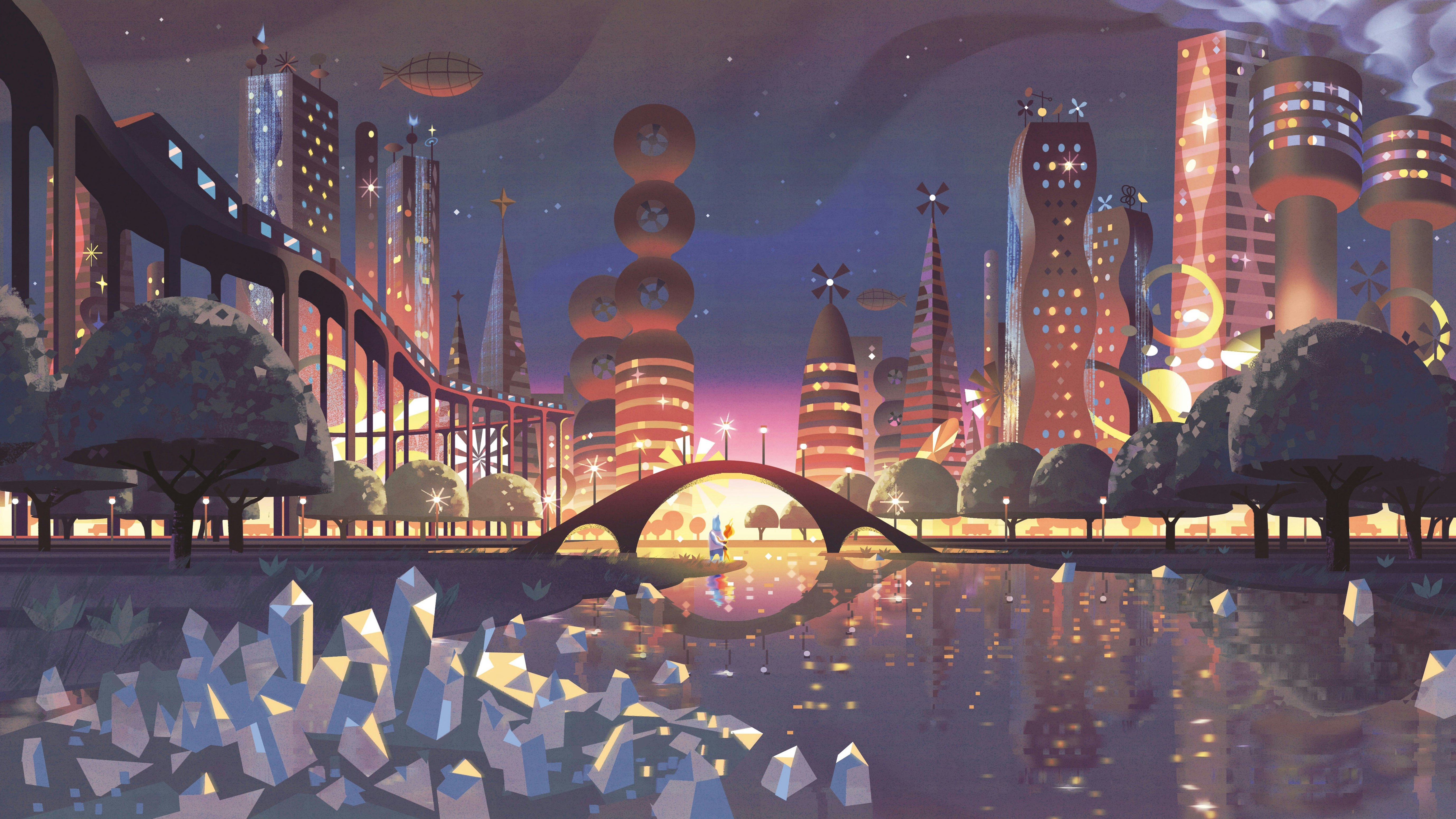

Where Do the Elements Live?

As for the world that Ember and Wade live in, the artists conjured up environments inspired by how each of the elements behaves. For the fire neighborhood of Element City, the buildings consist of materials they give rise to, such as ceramic, metal, or terracotta glass. There are also objects like cooking pots, stove burners, gas lamps, and fireplaces in this part of town.

Meanwhile, the water people have towers that call to mind dams with stunning arcs. Another structure in their district takes its shape from a Galileo thermometer, with each of the bubbles in it taking the form of a floating apartment. For the air folks, they designed kite-like complexes and a sports stadium in the shape of a cyclone that features prominently in one of the film’s most technically imposing sequences. When Ember and Wade attend a game at this venue, we see the cotton candy-like composition of the air people, but also the water people in the crowd doing a literal wave around the stands.

“Our ultimate goal was to make sure that all the various elemental buildings felt like they belonged together, along with the elemental characters all in one world,” said Shenk.