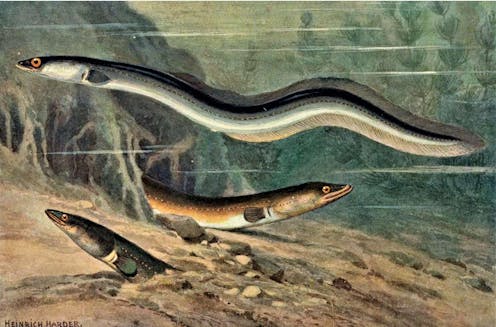

Few animals have sparked humanity’s curiosity as much as the eel (Anguilla anguilla). Until a recent past, this slimy, slippery, snake-shaped, incredibly agile fish inhabited virtually every body of water in Europe and Northern Africa, often in mind-blowing abundances. And nobody knew where they came from.

Philosophers and naturalists from Aristotle to Linnaeus were fascinated by the eel’s apparent lack of reproduction. Sexual organs or eggs had never been observed, so scholars generated diverse and imaginative explanations for the existence of eels.

It was not until the late 19th century that the marine origin of eels was uncovered. Italian zoologist Giovanni Grassi found that a leaf-shaped marine fish which had been described as Leptocephalus brevirostris was in fact a European eel in one of its juvenile stages. Grassi observed these leptocephali larvae metamorphosed into glass eels when they arrived close to the coast, and later grew into yellow eels. So, eels came from the sea. But the sea is very big.

Johannes Schmidt was a Danish biologist who decided to find the breeding grounds of the eel. He had observed that leptocephali larvae varied in size and deduced that the smaller they were, the nearer they would be from spawning areas. Schmidt undertook the herculean task of capturing and measuring juvenile eels across the Northern Atlantic, and published his results a century ago. Since that seminal publication, it has been assumed that the European eel spawns in the Sargasso Sea.

Strikingly, we have barely added any knowledge on eel reproduction in the last 100 years. A recent report that tracked eel reproductive migration has been highlighted for providing the first direct observation of eels migrating to the Sargasso Sea to mate. This result confirmed Schmidt’s ideas.

We just love eels

Whether aware of the mysterious life cycle of the eel or not, people have always eaten them. Eels’ remains are common in archaeological sites across Europe. They were appreciated by ancient civilisations in Egypt, Greece and Rome.

In medieval England, some taxes were paid in eels, involving the delivery of millions of animals. Historical documents from the 16th and 19th centuries report eels of up to 80 cm and 11kg caught in central Spain. Large-scale eel fisheries grew in several European spots, such as the Po River Delta, in Italy, where data of eel harvest have been kept since 1780.

A diverse set of cultural traditions have evolved around the eel. Across Europe it is consumed fried, grilled, dried, salted, smoked, boiled, and stewed in a variety of ways. Eel-eating parties and festivals exist in several places, such as the Sagra dell’Anguilla, in Comacchio (Italy), or the Swedish Ålagille.

Coastal areas of the Gulf of Biscay, and particularly Basque territories, developed a popular taste for glass eels that only recently expanded to other areas as a gourmet delicacy. Glass eels also have their own gastronomic festivals, such as the one celebrated in early March in Asturias, Spain.

We have grown quite fond of eating eels. But now all this has to stop.

The eel collapse

The European eel initiated a sudden decline around the late 1970s. All available data consistently show that current eel abundance is only a shadow of what it used to be a few decades ago.

Today, fewer than five glass eels arrive on European coasts for every 100 that used to arrive in the period from 1960 to 1979. Shrinking numbers are mirrored in the loss of occupied range. In the Iberian Peninsula, over 85% of originally suitable eel habitat is now unreachable for the species due to dams.

The conservation status of the European eel is so poor that it is now considered a critically endangered species. This is the most extreme endangerment category, the last stop before extinction. Think of basically any global conservation icon (pandas, koala, polar bear) and they will invariably be in a healthier status than the eel. Other critically endangered species found in Europe include the European mink and the Balearic shearwater. Both are strictly protected species and important conservation efforts are underway to protect them.

You won’t find European mink or Balearic shearwater on menus, neither would they be served en masse at a culinary festival. But it does happen with eels. We are eating the European eel to its extinction.

The need to stop eating eels

Culinary and social traditions involving the consumption of eels arose when our appetite could be fed by an abundant eel population. This scenario has not existed for decades now. But we are maintaining and even intensifying our traditions as if nothing had changed.

We have not stopped fishing despite the increasing scarcity of eels. In fact, the eel has become an exclusive, extremely expensive food item, which is increasingly desired due to our taste for rarity. The self-fuelling process through which exploited and declining species have higher economic value only serves to promote the intensification of exploitation and causes further decline. It is known to be driving some species to extinction. The eel seems to be one of them.

In the current situation the sustainable exploitation of eels is not possible. While there is room to discuss whether overfishing has played the main role in the eel decline or not, eel exploitation is undoubtedly one of the main obstacles for eel recovery. We have to stop fishing and consuming eels, both to avoid their extinction and to allow the future exploitation of a healthier eel population.

The zero-catch advice provided by eel experts should ideally be implemented across the species range and for a substantial amount of time (i.e., at least a decade).

However, European Union politicians at all levels are short-sighted on the matter and have avoided fishing bans. National and regional administrations are trying to overcome the timid, clearly insufficient restrictions imposed by the EU and protect fisheries’ right to fish eels.

Since we lack a top-down ban, consumers and the gastronomy community should play an important role in the abandonment of eel exploitation. Eel recipes are still widely publicised in the media and served in fancy restaurants. I want to believe that chefs and food journalists are simply unaware of the critical status of the eel, that they would support an eel exploitation ban if they just knew. There are good examples for the abandonment of eel as a cooking ingredient, such as that of UK’s Masterchef TV show. Now is the time for everyone to avoid eating, serving or recommending eels, completely.

Miguel Clavero Pineda receives funding for his research work from the SUMHAL project, financed by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation, through the European Regional Development Funds (ERDF): SUMHAL, LIFEWATCH-2019-09-CSIC-4, POPE 2014-2020.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.