Editors are almost always unseen and unheard – until something goes wrong. That might be a relatively minor mistake, such as a typo – as in a cookbook that mistakenly listed “people” instead of “pepper” in a recipe. Or it could be more substantial questions about the integrity of a book’s contents.

In 2018, Clinton Walker’s Deadly Woman Blues: Black Women & Australian Music was withdrawn from the market by its publisher, NewSouth, after it drew criticism from artists featured in the book. Aaron Corn and Marcia Langton asked in The Conversation, “How were its many obvious flaws permitted to go to press?”.

What is it exactly that we expect from editors? And are they starting to come out from behind the curtain?

Having worked in publishing for 15 years, a major change I’ve witnessed recently is the centring of ethical questions in discussions of editorial labour – from sensitivity reads intended to vet books for material that may cause offense, to editors protesting the publication of a contentious author’s work.

Editing is no longer a private task that one person performs on the writing of another. Then again, it never really was – Medievalists have long recognised the collaborations that underpin the publishing process, it’s only since the Romantic period, starting around the end of the 18th century, that we have glorified the lone author.

Reasons for keeping the editor’s work invisible have changed over time. The idea of the single author as solely responsible can be read as a result of the introduction of copyright law and a convenience for publishers. In what Dan Sinykin calls “the conglomerate era” (referring to the rise of the behemoth multinational publishers since the second world war), an invisible editor has become part of a general need to mask the workings of a publishing company that conflict with romantic notions of books and their creation.

But what are the consequences of having an invisible editorial workforce? And is it time for change?

Read more: 'The entire industry is based on hunches': is Australian publishing an art, a science or a gamble?

Editors as midwives

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that metaphors associated with editing are feminine – the most common identifies the editor as the midwife and the book as the baby. As a recent University of Melbourne survey showed, publishing workers are more likely to be female, white, have attended a private school and have poorer mental health than the national average.

For those in the industry, this is less a surprise than a confirmation of what we already knew. Being widely read, prepared to accept a low salary and taking on a kind of service role all align with this profile.

Another recent survey has shown wages are low (compared with teachers, not compared with lawyers). And that the gender gap between the (female dominated) lower levels of the workforce and (male dominated) upper levels persist. There has been an increase in gender non-binary staff since 2018, when Books and Publishing last conducted the survey – but this number remains small.

The survey also made clear that wages are decreasing in real terms. It reported a two per cent pay rise for editors in this time. The CPI has increased by 13.9 %.

A number of Australian publishing companies are privately owned (including Allen & Unwin, Text and Scribe), so their financials are not publicly available. But for multinational HarperCollins, global revenue grew 10% in 2022 to US$2.2 billion. Penguin Random House’s global revenue grew to €1.92 billion. Both companies make profits in the hundreds of millions of dollars.

Book publishing has continued to be profitable in recent years, compared with some other media businesses, such as newspapers, which have suffered considerably with changes to advertising revenue and the shifts to digital habits.

With continued robust income – even in the face of contemporary pressures such as supply-chain interruptions – why do publishing staff wages remain low? Could editors’ invisible labour be one of the reasons?

Invisible mending

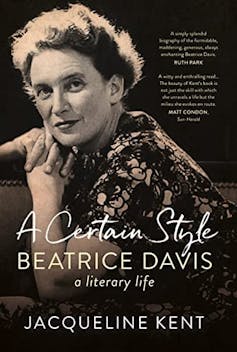

When editors speak about their work publicly, discussions are often bookended by comments around the importance of invisibility. Australia’s most celebrated editor, Beatrice Davis, who worked with some of the best-known authors of the second half of the 20th century, emphasised “invisible mending”. Davis, and other editors, insisted on the importance of keeping their work hidden for a few reasons – the greatest of which was maintaining the author’s confidence.

This is a persuasive argument for two reasons. Firstly, and self-evidently, it is the author’s name on the spine and their personal reputation at stake. Secondly, even though publishers are sometimes embroiled in legal proceedings over the content of their books, many publishers include a clause in their boilerplate contracts putting responsibility for the content with the author.

But Beatrice Davis was not simply moving commas around on the page, or even “just” making significant editorial suggestions. As well as developing authors’ ideas and their prose, Davis was shaping the national literary culture, notably as a judge for the Miles Franklin Literary Award – including in years that authors she edited were winners, such as Ruth Park, for Swords and Crowns and Rings, in 1978.

Although I know of no prizes currently judged by editors (other than for unpublished manuscripts), it remains true that editors exercise a kind of “social alchemy”. They “consecrate” the authors and their work, changing the work from a “natural resource” into a product – to borrow from sociologist Pierre Bourdieu.

Bourdieu describes editors in the American sense – what we call commissioning editors, or publishers – who select and advocate for books they publish. But it’s true that editors in the Australian sense – who work with the author to develop the book for publication, after a publisher has acquired it – are also responsible for refining a manuscript from its “natural state” into the versions readers eventually hold in their hands. (Or download to their e-readers.)

Read more: Friday essay: we are the voice – why we need more Indigenous editors

What’s next?

One of the consequences for the continued invisibility of editors is low pay for publishing staff – which has repercussions for the book industry. Radhiah Chowdhury, an editor and audiobook content development manager, identified low pay and lack of culturally and linguistically diverse people in management positions as some of the reasons for the relative monoculture that is contemporary Australian publishing, in her Beatrice Davis Fellowship report. The fellowship, created to honour the work of Beatrice Davis, is managed by the Australian Publishers’ Association and funds a research trip to develop a report on a particular aspect of the industry.

Discussions around a lack of diversity are not new. To take one example, Professor Anita Heiss has been advocating for changes to the industry since her 2003 book, Dhuuluu-Yala (To Talk Straight): Publishing Indigenous Literature. Increasingly, First Nations authors have been successful both in prizes and in sales, but there are very few First Nations staff in publishing companies (whether in editorial or elsewhere). This has attendant dangers, as Professor Sandra Phillips reminded us recently.

If invisibility leads to poor pay – and that is one of the impediments to achieving a more diverse workforce – then what can be done to change the status quo?

When I spent time visiting Chinese publishing houses in 2015, I learned it was not uncommon for editors to receive a share in the profits for the books they commissioned and/or worked on. (However, they also felt the effects of bad sales in their pay.)

Some Australian publishers offer profit-sharing for all staff. Is it time to look at more targeted iterations of this sort of program? Even if a profit-share model is not viable, addressing wages and conditions is crucial for developing a more diverse workforce and avoiding burnout.

Crediting editors

The easiest change to implement – one that is free and that we could start today – is to add the name of a book’s editors to every imprint page. It is standard to credit the designer and the printer. Often the font is listed. But with the exception of illustrated books, where entire teams are credited, editors rarely appear on imprint pages.

Including a discreet credit has an immediate two-fold benefit. It affords respect for editors’ contributions, and it could lead to more freelance work for editors (based on their track record). Such recognition would be equivalent to the credits on a film: many don’t watch the credits, but they nevertheless recognise the work of those who helped create the film.

A much bigger change – and a subject that deserves its own article – is recent instances of unionisation in the Australian book industry: at booksellers Readings (in Melbourne) and Better Read than Dead (in Sydney), and of editorial and marketing staff at Penguin Random House.

In the United States, around 250 unionised workers at HarperCollins recently went on strike, demanding a raise of the company’s minimum starting salary (from US$45,000 to US$50,000), and that it address the lack of diversity in its workforce. Australian publishing employees will continue to watch with interest.

Scholars in literary studies, history and sociology can also facilitate the recognition of editors by considering their contributions. There are prime examples of the richness of such work.

One is Matt Groenland’s The Art of Editing (2019), in which he examines two famous editing partnerships.

The first is Raymond Carver’s partnership with Gordon Lish, which is perhaps one of the most interventionist on record: Lish changed as much as 70% of Carver’s short stories. The other is David Foster Wallace’s partnership with Michael Pietsch, which includes a consideration of Pietsch’s editorial work on Foster Wallace’s posthumously published novel, The Pale King.

As publishing and editing studies become increasingly popular at Anglophone universities, more work like this would add to our understanding of editorial labour.

Discussions about publishing and the labour of its workers are already surfacing, both in academia and in the news media. Now is the perfect time to consider what it is that editors really do – and to both recognise their responsibilities and offer appropriate credit for their role in our reading lives.

Alice Grundy is affiliated with the Canberra Society of Editors and the Association for the Study of Australian Literature.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.