Eddie Redmayne’s performance at the 2024 Tony Awards in June has been a hot topic among theatre fans. British director Rebecca Frecknall’s imaginative revival of Cabaret (1966) opened in London in 2021 and on Broadway in April 2024. Broadway critics have not been as overwhelmingly positive as London’s – and Redmayne’s divisive portrayal of the iconic Emcee character is taking centre stage in the debate.

When thinking of Cabaret, Liza Minnelli’s glamorous, vocally masterful turn as Sally Bowles in the 1972 film might spring to mind. For some, Alan Cumming’s seductive, queer-coded Emcee in Sam Mendes’s 1993 revival might be fresher in the memory. Arguably, Cabaret’s most popular images are those that are sexy and gritty, evoking the exhilarating pleasure of a Weimar-era German cabaret club. The Emcee invites us to leave our troubles outside and focus on the beautiful performers – and we do.

The sinister implications of this invitation become obvious throughout the show, which portrays the dangers of escapist entertainment distracting audiences from reality. Cabaret’s headliner Sally Bowles is not interested in politics and turns a blind eye to the rise of Nazism. In the show’s original staging, this theme of political apathy, and entertainment’s role in it, was symbolised by a giant mirror that reflected the audience back to itself. Subsequent productions have found different ways of prompting reflection.

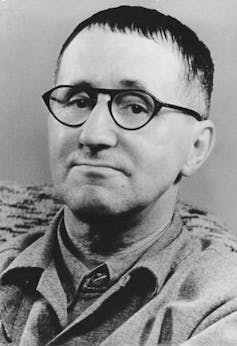

Strikingly, the artistic influences of Frecknall’s revival – grotesque art, expressionist movement, the theories of the playwright Bertolt Brecht – were all prominent in Germany before being banned by the Nazi government. In fact, the show’s aesthetics could be seen to represent the antithesis of Nazi art.

Additionally, Redmayne’s marionette-like movements evoke the puppet theatre popular at the time (such as the Salzburg Marionette Theatre, which became an instrument for propaganda under the Nazis). So if the Emcee is a marionette, who is controlling him?

Redmayne’s performance pays homage to German expressionism, an early 20th-century art movement that emphasised the artist’s feelings or ideas, rather than replicating reality. The contorted movements seen in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) and Nosferatu (1922) are replicated in his unnatural limb extensions and melodramatic facial expressions.

He also echoes some aspects of expressionist dance, a counter movement to classical ballet, which sought to convey feeling through unrestrained, grotesque, eerie movement.

The influential expressionist choreographer Mary Wigman (1886-1973) was often hunched over in her performances, and wore masks to dehumanise her face. Redmayne mimics an inhumane mask effect with his expressions, and he hunches over for much of the show. As per the spirit of Wigman’s practice, his jagged performance embodies the extreme rupture between Weimar and Nazi culture.

Brecht, a contemporary of Berlin’s cabaret scene, devised epic theatre as a remedy for escapist theatre, which he perceived as socially irresponsible due to the way it “intoxicates” viewers and discourages critical thought.

In Brecht’s plays, gestures were exaggerated, and costumes and makeup were bold and eye catching. His attitude to musical numbers was equally brutal: “They must be cold, plastic, unflinching and, like tough nutshells when they get caught in dentures, knock out a few of the listener’s teeth.”

In drawing attention to their own artifice, Brecht’s techniques created defamiliarisation, keeping audiences distanced enough to remember they were watching a play. Although his theories remain controversial, the Brechtian influences detectable in Redmayne’s performance are contextually significant given Brecht’s experience in Nazi Germany.

Redmayne at the Tony Awards

Critics of Redmayne’s Tony performance have called his rendition “creepy” and “scary in all the wrong ways”. Vulture critic Rebecca Alter, for example, resents that “this team thinks they need to spoon-feed and scream the ‘banality of evil’ messaging at you”.

Indeed, his performance is a hammer to the head compared to the flirtations of previous Emcees. Past productions lulled audiences with upbeat numbers and romantic subplots before sucker-punching them with the long-since-festering presence of Nazism. Ultimately, the theatrical spectacle that initially disguised this threat from the audience is revealed to be the very tool of fascist propaganda that the show is critiquing.

Instead of confronting the audience with a mirror (a clear symbolic device, but maybe not the most effective in provoking legitimate reflection), this revival invites us to reevaluate our perception of entertainment by considering how we feel about its more controversial changes.

Explicit discomfort is used to great acclaim in political drama, yet perhaps due to musical theatre’s associations with light-hearted entertainment, many consider it incompatible with the form. However, this kind of discomfort works brilliantly in Cabaret.

Redmayne’s critics might prefer to be thrilled and wooed in a familiarly sinister way, but Cabaret has been there and done that. While Joel Grey’s iconic Emcee (Grey originated the role on stage and in the film) is ambiguously menacing, and Cumming’s is charming and tragic, Redmayne’s hurls us out of our comfort zone. His demonic Emcee leans towards absurdist horror, shape-shifting through different forms before reaching his final, most chilling one – a pristinely dressed Nazi. He is frightening and affronting, but what’s wrong with that?

This production might be a little pretentious – and the ticket prices exorbitant – but you can’t deny that it’s captivating. Perhaps more musicals should take a leaf out of Redmayne’s nightmare-fuel playbook.

Jodie Passey does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.