Ecology has always fascinated Australian artists. Think of landscape painters like Arthur Boyd (1920–99), who was inspired by nature and committed his career and legacy to protecting it.

Boyd spent the latter part of his life painting the Shoalhaven River at Bundanon, New South Wales. The use of the land along the river for agriculture was causing erosion, disturbing soil, plant and animal life. With increased tourism and intensified use of the river, Boyd feared further destruction, and so Boyd and his wife bought land along the river during the 1970s – gifting it to the Australian people in 1993.

Since scientific studies began showing the undeniable human impacts on the climate, ecology and art have been brought together in new and urgent ways.

Ecological art can communicate the results of scientific studies, create opportunities for community-based interventions, and can even function in their own right as restorations of ecological systems.

Ecology and art

If you have ever enjoyed Sydney Park you were visiting the integrated environmental artwork Water Falls by Jennifer Turpin and Michaelie Crawford.

Water Falls consists of two sets of terracotta troughs, arranged in dramatic zig-zagging lines. As part of a constructed wetland ecosystem, the artwork harvests stormwater from the surrounding streets, preventing flooding and providing habitat for native animals. It is experienced as the rhythmic sight and sound of falling water. Ecology as art.

Ecological artists deal with the politics, language, culture, economics, ethics and aesthetics of ecology in ways that scientists sometimes fall short.

In 2012 and 2021, Tega Brain engineered an artificial wetland system which could also wash dirty clothes. Coin Operated Wetland shows how water, although often made invisible by the urban life it sustains, is always circulating and part of us and our cities.

Many First Nations artists have pointed out the entanglements of language and Country with ecological knowledge.

Quandamooka Artist Megan Cope makes sculptural installations that engage with local ecological systems. In her work Kinyingarra Guwinyanba (“a place of oysters”, 2022), she plants sea gardens with oysters to create “a living, generative land and sea artwork that demonstrates how art can physically heal country”.

Ecological art brings scientific language into the gallery and into our conversations. Using language in different ways can be a way of rethinking human relationships to land, water and atmosphere.

Topographies

There are currently two exhibitions in Sydney showcasing interdisciplinary research on climate change communicated in artistic ways.

Topographies at the Sydney College of the Arts engages with topography: the study of the forms and features of land surface. Curator Vicky Browne describes topographies here as “the process of marking out the shape of the world”.

Magnetic Topographies, an artist collective who are featured in the exhibition were in residence in Bundanon in 2023. They extend topographic research to “avian navigations”, “earthly togetherness” and “repellent terrain”.

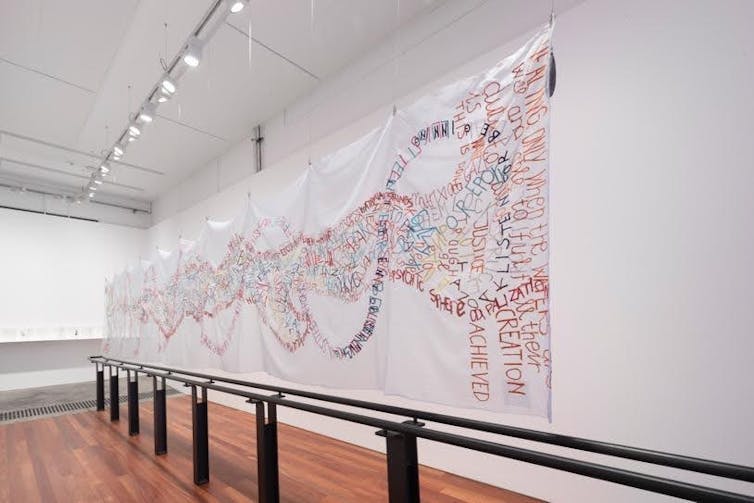

Biljana Novakovic’s Listen for the Beginning (2024) is an enormous piece of light blue fabric is embroidered with coloured words and phrases layered over one another, an interpretation of Gooliyari, known as Cooks River, Sydney, and sometimes as Australia’s sickest urban river.

Ben Denham’s work A Topography of Air (2024) is a collection of multisensory ecological communications and interventions. Custom electronics, barometric pressure sensors, modular synthesisers and wooden boxes are combined with dried native grasses and “the atmosphere”. We feel as though we are in a laboratory – but we are not quite sure of the experiment, or what is being measured.

Alongside this work is another piece by Denham. Generalised Diagram (2024) employs the visual language of science in the form of a flow chart, black lines on a white page, pinned to the wall, showing feedback loops between oscillators, amplifiers, bodies, politics and the atmosphere.

Denham’s sculpture and flow chart work together to explain how to understand features on maps, in graphs, and in the terrain in sensory ways. “We see the visual form on a map, we feel pressure gradients on our skin,” Denham explains.

Living Water

At the University of New South Wales Library, Living Water celebrates 75 years of water research from faculties and institutions across NSW.

The River Ends at the Ocean is a collaborative project engaging with diverse knowledge about Gooliyari.

In 2021, Aunty Rhonda Dixon-Grovenor, Astrida Neimanis and Clare Britton led a group of approximately 60 walkers along the concreted banks, restored edges, and straightened channels of the estuary, following the tide out to Kyeemagh Beach.

At the entrance to the exhibition, a film of the walk by Aunty Rhonda Dixon-Grovenor layers over a flowing sketch by Britton of the Cooks River and its tributaries.

The drawing is based on the Cooks River Environment Survey and Landscape Design: Report of the Cooks River Project (1976) and helps us understand how the river catchment, and ecological knowledge about it, has changed over time.

Another collaborative creative work, Rippon Lea Water Story, (2023) explores waters, memory, plant and animal life, and infrastructure at Rippon Lea, a colonial estate in Melbourne on Boon Wurrung Country.

In the dark space of the gallery, we are asked to listen deeply to the sounds of Melbourne’s subterranean waterways, recorded with specialist microphones called hydrophones. These underwater microphones were developed by scientists to record biotic, abiotic and anthropogenic sounds in marine environments.

Here, these recordings allow us to hear the sounds of water flowing underneath the concrete surfaces of the city.

Moving forward with art and science

Visual artists synthesise and represent different types of knowledge and language.

The exhibitions are bringing new audiences to ecological science and developing understandings needed to convince people and organisations to take action on climate change.

Alexandra Crosby receives funding from the Australian Research Council

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.