The island of Rapa Nui, also known as Easter Island, never had a catastrophic population collapse, a new study proposes.

The finding may upend decades of assumptions about how overexploitation of the landscape by the Indigenous people of Rapa Nui, known as the Rapanui, caused a supposed rapid rise and catastrophic fall before any Europeans arrived. The research, which used a type of artificial intelligence called machine learning, suggests that the Rapanui population was sustainable, never going above 3,900 people. However, experts who were not involved in the study have critiqued the research, pointing out weaknesses in the data.

Located over 2,300 miles (3,700 kilometers) from the nearest mainland, Rapa Nui is one of the world's most remote locations to be inhabited by people. Rapa Nui was first settled around 1000 A.D., likely by people from Polynesia, who regularly traded with people living on the South American continent. Famous for its moai — giant stone statues of human figures — Rapa Nui is also known for palm tree deforestation and the overexploitation of resources, which have been cited as major factors in the decline and collapse of Rapanui culture.

While it is true that the small island — which is just 63 square miles (164 square kilometers), or slightly smaller than Washington, D.C. — has poor soil quality and limited freshwater resources, researchers have discovered that the story of the Rapanui is one of survival in challenging ecological conditions.

One method the Rapanui used to enhance the island's volcanic soil was "lithic mulching," or rock gardening, in which pieces of rock were added to cultivation areas to boost productivity. The rock gardens generated better airflow in the soil, helping mediate temperature swings and maintaining nutrients — including nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium — in the soil.

Archaeologists have researched both rock gardening and soil fertility on Rapa Nui to better understand food cultivation and historical land usage, including quarrying for the creation of moai. While some experts have suggested that the island may have been able to support 16,000 Rapanui people at its height in the 15th century, the new study has reevaluated the population size, suggesting it was never more than 3,900 people.

Related: Polynesians and Native Americans paired up 800 years ago, DNA reveals

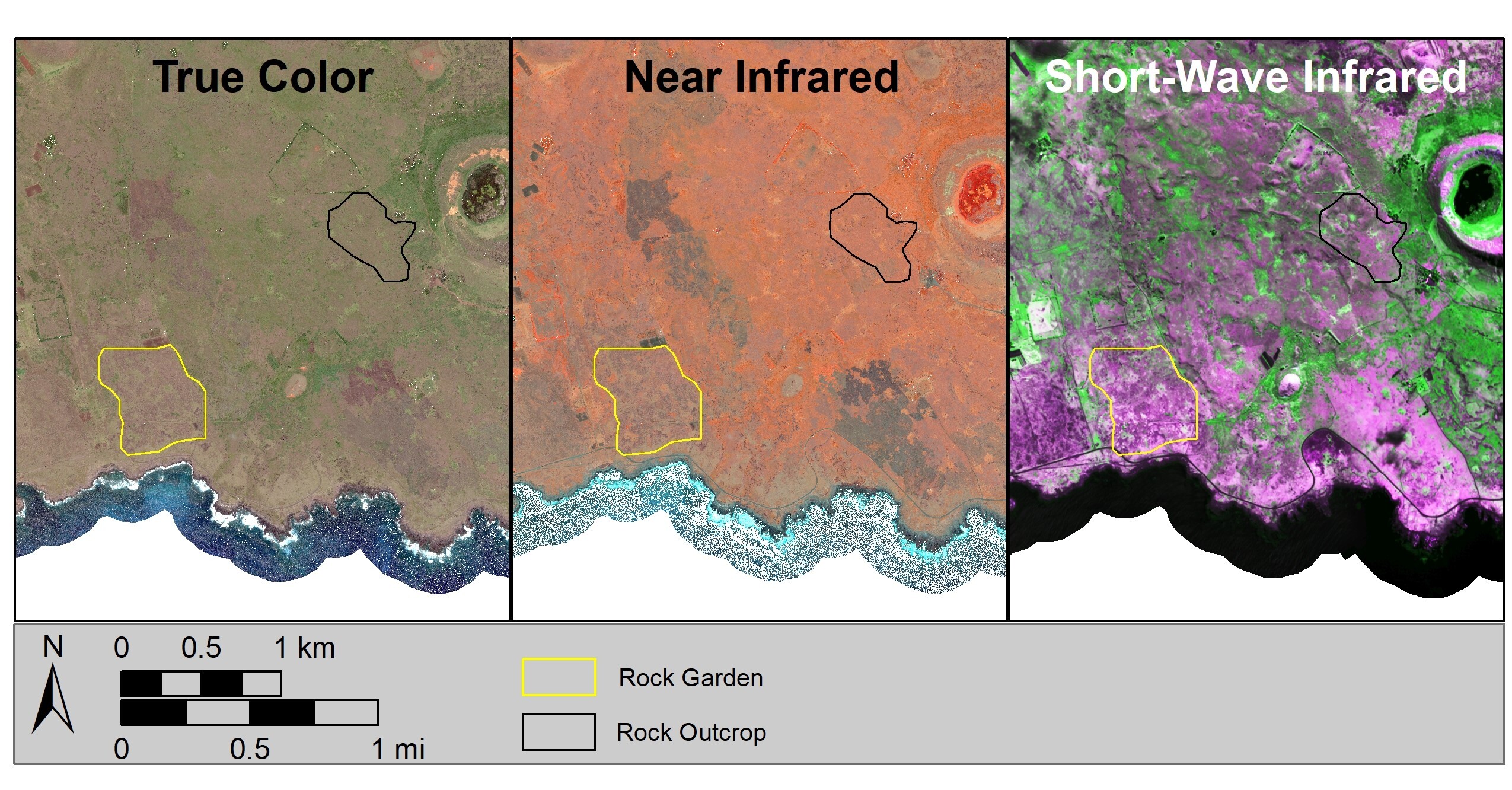

In the study, published Friday (June 21) in the journal Science Advances, researchers used shortwave infrared satellite imagery (SWIR) and machine learning to identify rock gardens on Rapa Nui. Satellites record different wavelengths of light reflected from the Earth's surface, and the SWIR data produced can reveal rock gardens, vegetation, natural rock formations, and bare soils due to their differing moisture and mineral contents. In looking at satellite imagery from the island, the researchers discovered that rock gardening was significantly less prevalent than previously assumed. According to the new study, baseline estimates of the population size using the new rock-gardening data suggest that the island could not have sustained more than 4,000 people at a time.

The Rapanui "had to figure out how to survive every single day, producing food and getting water and the other resources they needed, despite the fact there were simply no other alternatives for them to turn to when things got tough," Carl Lipo, an archaeologist at Binghamton University, State University of New York, and one of the study's authors, said at a June 18 news conference.

"The way in which the communities were organized, the way in which they cooperated as well as competed with one another, I think are important ingredients for how people can survive in a limited landscape with very limited options," Lipo said.

But other experts are not convinced. "This study presents a new finding that is contrary to nearly all other archaeological literature for Rapa Nui on this subject," Jo Anne Van Tilburg, an archaeologist at UCLA and the director of the Easter Island Statue Project, told Live Science in an email.

Van Tilburg suggested the idea of a low-but-sustainable population is an "overreach" because the study authors used only one kind of evidence — rock gardening — for their model, oversimplifying the nuances of soil fertility across the island.

"Without factoring in all components of the Rapa Nui subsistence patterns, not to mention chronology, how is it possible to conclude the system was or was not sustainable?" Van Tilburg said. Even taking the rock-garden data on its own does not necessarily lead to Lipo and colleagues' conclusions, Van Tilburg suggested, as the small number could be evidence that they were "unsuccessful adaptations that inadequately fed a fast-growing population."

However, the newly published population number is similar to what Europeans encountered when first arriving on Rapa Nui in 1722. But while Europeans assumed that this was a depopulated island, "what we're finding archaeologically is the fact that 3,000 is probably around the sustainable population size of the island given the kind of subsistence strategies that they were doing," Lipo said at the news conference. "This surprising island really still invites a lot of new investigations to figure out what happened there."