Scientists have discovered exactly how earthquakes trigger quartz into forming large gold nuggets — finally solving a mystery that's puzzled researchers for decades.

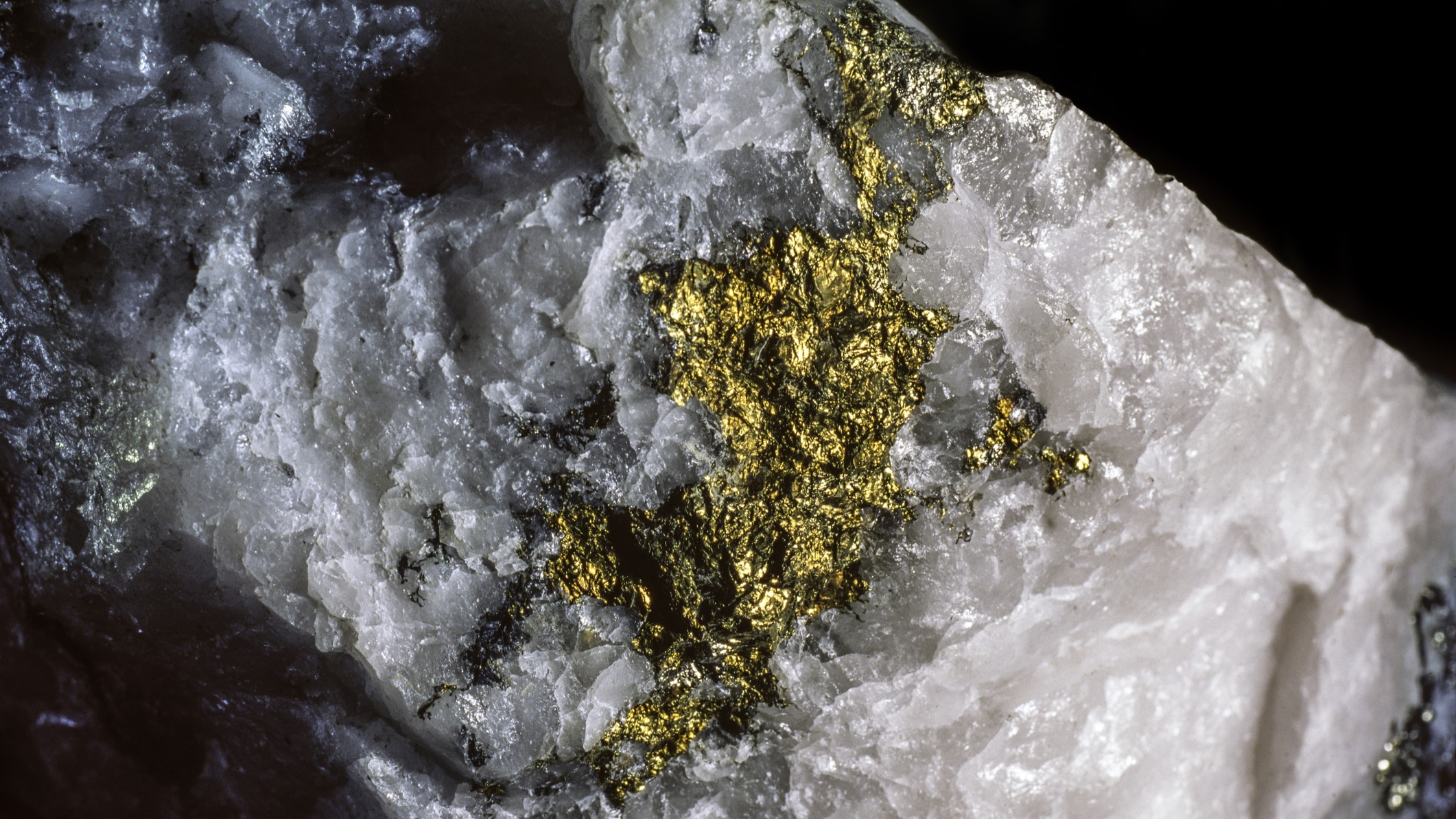

Gold naturally forms in quartz — the second-most abundant mineral in Earth's crust after feldspar. But unlike other types of gold deposits, those found in quartz often cluster into giant nuggets. These nuggets float in the middle of what geologists call quartz veins, which are cracks in quartz-rich rocks that periodically get pumped full of hydrothermal fluids from deep within the crust.

"Gold forms in quartz all the time," said Chris Voisey, a geologist at Monash University in Australia and the lead author of a new study published Monday (Sept. 2) in the journal Nature Geoscience. "The thing that's weird is really, really large gold nugget formation. We didn't know how that worked — how you get a large volume of gold to mineralize in one discreet little place," Voisey told Live Science.

Hydrothermal fluids carry gold atoms up from the deep and flush them through quartz veins, meaning gold should theoretically become evenly spread in the cracks rather than concentrated into nuggets, Voisey said. These nuggets are exceptionally valuable and represent up to 75% of all the gold ever mined, according to the study.

Two separate clues helped Voisey and his colleagues solve the gold nugget mystery, he said. The first was that the largest nuggets occur in orogenic gold deposits, which are deposits that form during earthquakes. The second was that quartz is a piezoelectric mineral, meaning it creates its own electric charge in response to geologic stress, such as the stress generated by earthquakes.

Related: Why is gold so soft?

"When you actually put it together, it almost works out a bit too neat," Voisey said. The researchers found that earthquakes fracture rocks and force hydrothermal fluids up into the quartz veins, filling them with dissolved gold. In response to the stress of the earthquake, quartz veins simultaneously generate an electric charge that reacts with the gold, causing it to precipitate and solidify.

Gold concentrates in specific spots because "gold dissolved in solution will preferentially deposit onto pre-existing gold grains," Voisey said. "Gold is essentially acting as an electrode for further reactions by adopting the voltage generated by the nearby quartz crystals."

This means that in quartz veins, gold solidifies into clusters that grow bigger with each earthquake. The largest orogenic gold nuggets found to date weigh around 130 pounds (60 kilograms), Voisey said.

To test this idea, the researchers simulated the effect of an earthquake on quartz crystals in the laboratory. They submerged the crystals in a liquid containing gold and replicated seismic waves to generate a piezoelectric charge. The experiment confirmed that under geologic stress, quartz can produce a large enough voltage to precipitate gold out of solution.

The simulation also confirmed that gold preferentially solidifies on top of existing gold deposits in quartz veins, which helps explain the formation of large gold nuggets.

"Having pre-existing gold and having it become basically the catalyst or the lightning rod that other gold would attach to was very, very exciting," Voisey said.

One of the implications of the study is that scientists can now make large gold nuggets in the lab, "but it's not alchemy," Voisey said. "You'd have to have gold in a solution and then you just move it from basically being in a liquid to sticking to something else."

However, the results don't give geologists and exploration companies new clues as to where to mine for gold nuggets. The best science can offer for now is a device that detects piezoelectric signals from quartz at depth, Voisey said. "This can tell you where quartz veins are — but not tell you if there is gold in those quartz veins."