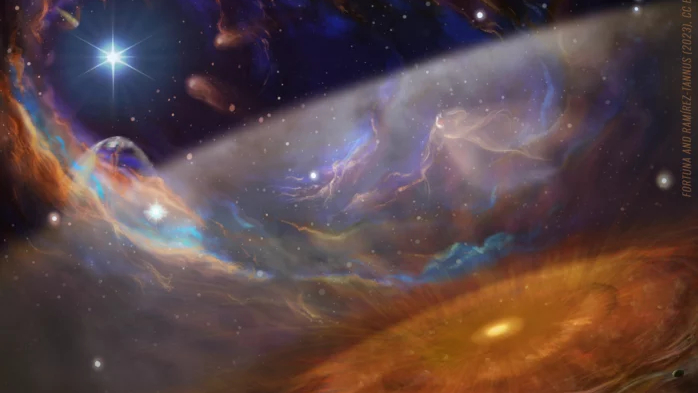

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has found water and organic carbon molecules near a massive, active young star that's situated in a faraway star-forming region of space, suggesting Earth-like exoplanets could form even in the harshest environments in our Milky Way Galaxy. Potentially, some of those exoplanets may even exhibit habitable conditions.

A team of researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy (MPIA) in Heidelberg, Germany, aimed the mighty James Webb Space Telescope at a star-birthing region known as NGC 6357. The crew's goal was to analyze the chemical environment surrounding the cluster's budding stars and see whether their orbits could possibly host life.

Located some 5,500 light-years from Earth, NGC 6357 is one of the closest regions to us in which we see massive stars currently forming. As these energetic, young stars ignite amid thick clouds of dust, they begin to lash their surroundings with powerful stellar flares and intense ultraviolet radiation, creating unforgiving environments in their vicinity. But the new study found that a planet-forming disk surrounding one of the stars in this cluster contains molecules that are prerequisites for life as we know it, such as water and carbon dioxide.

"This result is unexpected and exciting!" María C. Ramírez-Tannus, an astronomer at MPIA and lead author of the new study, said in a statement. "It shows that there are favorable conditions to form Earth-like planets and the ingredients for life even in the harshest environments in our galaxy."

Related: James Webb Space Telescope finds water and methane in atmosphere of a 'warm Jupiter'

The planet forming disk in question, officially designated as XUE-1, surrounds a star about as big as our sun. But that star’s much larger, and more vicious, siblings are not far away.

Prior to the deployment of the James Webb Space Telescope, astronomers could only peer into planet-forming disks located much closer to Earth than XUE-1, which means this disk is now the most distant ever studied in such a detail. Moreover, none of the nearby, previously studied disks live in a cluster containing stars as young, or as massive, as those in NGC 6357.

These findings are good news for life in the universe as they dispel concerns that potentially habitable planets could not form too close to very massive stars. Previously, scientists thought the intensity of ultraviolet radiation produced by massive stars would interfere with the distribution of dust and gas in planet-forming disks, possibly preventing the formation of rocky planets like Earth, for instance. The NGC 6357 cluster contains more than ten super bright and massive stars, suggesting most of the cluster's matter is exposed to high levels of UV radiation.

"If intense radiation hampers the conditions for planet formation in the inner regions of protoplanetary disks, NGC 6357 is where we should see the effect," Arjan Bik, an astronomer at Stockholm University, Sweden, and second author of the paper, said in the statement.

But the results of Webb's observations showed that the chemical composition of the XUE-1 disk is not too different from those present in quieter parts of the galaxy.

In addition to water and carbon dioxide, the JWST detected traces of carbon monoxide and acetylene in the inner region of the planet-forming disk as well as silicate dust, which plays an important role in planet formation.

The researchers hope to learn more about the possible existence of life in NGC 6357 going forward. They plan to aim the famous telescope at yet another 14 dust disks located in different parts of this harsh stellar cluster.

The new study was published in the journal Astrophysical Journal Letters on Thursday, Nov. 30.