Lalbagh, a garden boasting a rich history spanning over two centuries, was initially conceived and laid out during Hyder Ali’s dalavaiship in Mysore kingdom. Its subsequent management by various British Superintendents continued until India’s Independence. Lalbagh played a pivotal role in introducing and proliferating both ornamental and economically valuable plants within Bengaluru city.

Numerous accounts and M. Fazlul Hasan’s book Bangalore Through the Centuries assert that Lalbagh drew inspiration from Pondicherry’s verdant gardens. This book delves into gripping historical events and underscores the uniqueness of Lalbagh’s inception. It recounts Haider Ali’s enchantment with the lush gardens of the French settlement in Pondicherry, a lasting impression that fuelled his establishment of Lalbagh in Bengaluru. This act can be seen as a homage to the remarkable French gardening expertise, he notes.

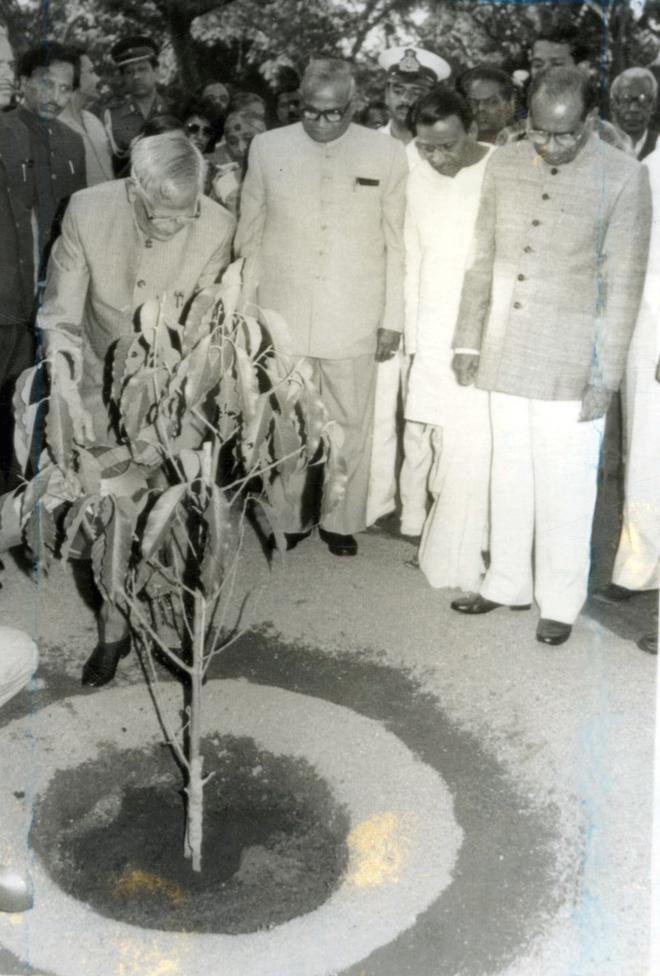

Nurtured by local communities

Suresh Jayaram’s book Bangalore’s Lalbagh: A Chronicle of the Garden and the City further elaborates on the concept of historical gardens. These gardens, nurtured by local agricultural communities during Kempegowda’s reign, evolved through Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan’s baghs (gardens) in the 18th century, culminating in the colonial gardens. Lalbagh became a convergence of multiple trajectories, blending aesthetic and economic functions, he notes.

Since the 18th century, Bengaluru became a haven for the elaborate baghs of Hyder and Tipu, influenced by the Persian and Indo-Persian Charbagh tradition. These enclosed pleasure gardens, known as “hortus conclusus,” featured systematically planted fragrant flowers and fruit-bearing trees. The hallmark of these gardens was their division into four equal parts.

The first of these baghs was established by Hyder Ali, the nawab of the erstwhile princely state of Mysore. During his rule, he created three gardens, including Srirangapatna (also known as Lalbagh), Malavalli, and another in Bengaluru. Hyder Ali is credited with marking the initial boundaries of the Lalbagh Botanical Garden, located a mile east of Bangalore Fort and near the Kempegowda watchtower, built by Kempegowda II, spanning around 40 acres at that time. He drew inspiration from the lost Mughal-style garden in Sira, near Tumakuru.

The book by Suresh Jayaram reveals that Hyder Ali was a devoted follower of Sufism, and his son Tipu was named after the Sufi saint Hazrat Tipu Mastan Auliya from Vellore, Arcot. Beyond Lalbagh’s walls lies the Masjid-e-Meraj Bade Makaan and a sizable well supplying water to the shrine and its surroundings. The story goes that Hyder Ali observed the congregation of devotees arriving in bullock carts to seek the saint’s blessings, prompting him to establish a garden, one of several adjoining Lalbagh, to offer shade and respite. Adjacent to the masjid is a Muslim cemetery, representing the farthest extent of the original Lalbagh. Hyder’s Lalbagh followed the Charbagh layout, complete with fountains and canals, enclosed by a geometric wall protecting it from the external world.

The garden provided a multisensory experience, with water mirroring the sky and trees offering both shade and delectable fruits like pomegranates, figs, citrus, and mangoes, which attracted local birds. Flowers like jasmine and roses contributed hues and scents, offering relief from the otherwise rugged landscape, says author Suresh Jayaram.

Exotic varieties

The book also details how Hyder imported plants and trees from Delhi, Multan, Lahore, and Arcot, showcasing the diversity of species that adapted to varying climatic conditions. His son Tipu continued this tradition. “He collected several important native and exotic species of flowers, fruits, vegetables and other plants, obtained from several far off places such as Malacca, Isle of France, Oman, Arabia, Persia, Turkey, Zanzibar, France and other European countries,” notes the Horticulture Department website.